Eight nature books to change your life

María Medem

María MedemIs it possible to reboot or 're-wild' our minds by living a slower, more feral existence in harmony with nature? Lindsay Baker speaks to the authors who think we can.

The movement towards rural living in the western world seems to be a sign of the times, with an exodus from urban life, and people seeking a rustic idyll, a simpler existence – and in some cases embracing the idea of "slow living", an antidote to fast hustle culture. And the lure of rural life is inevitably even more acute in spring and summer, when there is a sense of renewal and expectation in the air, and as, the poet Philip Larkin famously put it: "The trees are coming into leaf/ Like something almost being said".

It's no surprise, then, that the theme for the US's Mental Health Month this year is "back to basics". In fact, increasing numbers of people are responding to burnout and the stresses of modern life by moving completely off-grid, in what has been described as "extreme wilding". In an attempt to reset their lives and their expectations of life, they are going beyond the cottage-core notion of a cosy, tidy garden and a cute, nostalgic rural aesthetic, and are placing themselves in truly remote and rugged landscapes.

More like this:

The sense that a close connection with nature can be life – and mind – changing is shared by a number of recent books. The idea of re-wilding is familiar, with many reforestation projects and the re-introduction of endemic flora and fauna happening across the globe, helping to restore eco-systems and reverse some of the damage done to wild environments. But in a moment when mental health problems are rife, and as we start to emerge from the worst pandemic the world has known for a century, the term rewilding is now being used in a new way.

So can we re-wild ourselves? Just as our natural environment can be healed, can our minds also, particularly after a period of crisis or trauma? That is the contention of several recently published or upcoming books, which suggest that through our connection with nature, our own mental eco-systems can be restored or rebooted, our lives re-appraised and reset, and emotional damage reversed. In addition, they suggest, this process can help us to make sense of the world – and that while nature is helping us, we can be helping it. For these authors, the idea of nature as something that is separate from us is coming to an end.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe complex interdependence between us and the creatures with which we share the Earth is explored in the New York Times best-selling novel Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy. It tells the visceral story of a woman's quest to reintroduce wolves to the wilds of Scotland. Inti Flynn, a biologist, arrives in the Highlands with her traumatised twin sister and 14 grey wolves. In the process of reintroducing the wolves to their natural habitat, Inti hopes also to help her sister Aggie heal, after horrific events that drove them both out of Alaska.

In an urgent plea to restore our connection to the world before it's too late, Booker prize-winning writer Richard Flanagan recently wrote the novel Living Sea of Waking Dreams, a magical realist tale set against the backdrop of the Australian bush fires. Meanwhile, Seven Steeples by Sara Baume, an "astonishing prose poem", tells the story of a couple who withdraw completely from city life , retreat to the foot of a mountain in the remote countryside, and lose themselves in their rugged surroundings.

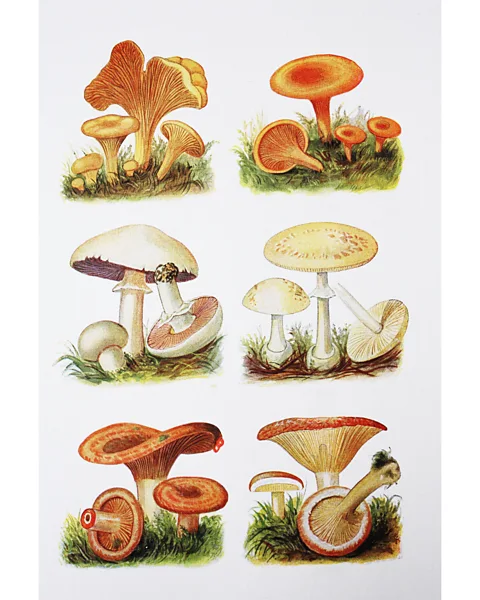

The re-wilding of the mind is viewed from a different perspective in Merlin Sheldrake's hit non-fiction book Entangled Life: How Fungi Make our Worlds, Change our Minds and Shape our Futures. In this deep dive into the world of fungi, the author explores how the organisms have influenced contemporary philosophy, and how, in the "anarchic" way they grow and connect with each other and other organisms, they represent a highly sophisticated "more than human world".

Sheldrake sees how fungi lives as a model for humans: "Fungi have changed my understanding of how life happens. These organisms make questions of our categories, and thinking about them makes the world look different." Like fungi, he writes, "we are ecosystems that span boundaries and transgress categories. Our selves emerge from a complex tangle of relationships." How, the book asks, can we be more like fungi?

Entangled Life also explores how humans have engaged with fungi in various ways, from farmers to herbalists and cultivators growing hallucinogenic psilocybin at home, and it highlights the recent mainstreaming of psilocybin therapy, which, it has been suggested, is able to "reset the depressed mind". The winner of the Wainwright Prize, Entangled Life has been a surprise global hit for the debut author.

And out in June is the much anticipated memoir Birdgirl by Mya-Rose Craig, a 20-year-old ornithologist, environmentalist and diversity activist. So far in her life, Craig has seen more than 5,000 types of bird, half of the world's species, across all continents of the globe. "It's a memoir about my childhood birding around the world," she tells BBC Culture. "And my love of these tiny creatures which are such a central part of my being, my family, and coping with mental illness within it. It's hugely personal." Birdwatching for her is the "thread running through the pattern of my life," she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe memoir explores how each bird sighting is a step towards the author finding her own voice, as well as a step in her family's challenging journey. Each new bird spotted is also a "moment of peace" amid the turmoil of her mother's worsening mental health crisis. Craig is also the founder of Black2Nature, an organisation that runs camps, workshops and campaigns to make the nature conservation and environmental sectors ethnically diverse. "At my nature camps," says the British-Bangladeshi author and campaigner, "I teach the children about nature engagement, how it makes them feel and how they can use that to be more resilient and be able to overcome problems."

Birdgirl also explores how the mindful act of looking for birds has made Craig more determined to campaign for the environment's – and all of our – survival. The memoir is a logical progression from her previous book, We Have a Dream, which explored how young indigenous environmental activists are bringing change, and also explored our interdependence with nature. "We Have A Dream shows us that it is not too late to act and make a difference in rejuvenating nature, as it is waiting to be given the chance to fight back," she says, pointing to the example of Lesein Mutunkei from Kenya who is featured in the book. "His goals for trees are so clever, and yet so simple – showing us that it is not too late to rewild and save ourselves from an ecological disaster."

After all, the idea of renewal and rewilding works both ways, says Craig. "I think that whilst many of the young people in We Have A Dream understand that our natural environment has an amazing capacity to renew, self-repair and regenerate, their message was that humans had relied on this for too long, and we were now at the point where the Earth had been pushed too far and it could no longer regenerate. The hope coming from the book is not that our planet will recover if left alone but that here were a young generation who are fighting for big change.

"I believe that nature is really important to us as humans and that it is essential for us to remember that we are part of nature, that whilst nature needs us, we also need nature."

Tree of life

The way in which we are nurtured by the natural environment, while simultaneously ourselves nurturing it, is also explored in a newly published volume of journals, with an introduction by Tilda Swinton, by the late film director Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook. It tells the story of the creation of his garden at Dungeness, in an arid, windswept spot near a nuclear power station. "I planted a dog rose," he writes. "Then I found a curious piece of driftwood and used this, and one of the necklaces of holey stones on the wall, to stake the rose. The garden had begun. I saw it as a therapy and a pharmacopoeia." The garden was an ever-evolving circle of stones, plants and sculptures created with foraged driftwood and flotsam, cultivated in the harshest of conditions, and remains to this day a source of wonder for visitors.

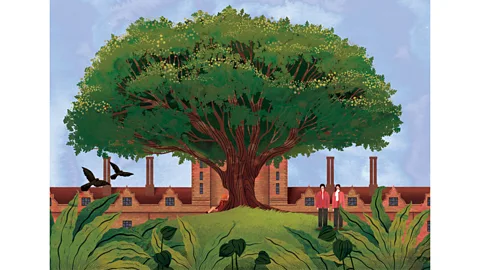

This idea that nature has wisdom to teach us and lessons to impart also features in The Great British Tree Biography, in which Mark Hooper explores the history and folklore of Britain. In it, notable trees' stories are told, from Knole Oak, immortalised by Virginia Woolf in Orlando and in the video for the Beatles song Strawberry Fields Forever, to the oak on Isle Maree in Scotland that is said to provide release from madness to visitors who offer coins. The author says that, having grown up in the countryside, the woods have always been his "happy place". So what do these landmark trees tell us about history, life and ourselves?

Some of the chapters in his book, Hooper tells BBC Culture, are about "the tree itself and what it stands for, as a metaphor for values we hold dear. Robert the Bruce used a 2,000-year-old yew tree, growing through the rocks on the shore of Loch Lomond, as a symbol of endurance as he tried to raise the spirits of his retreating army in 1306. Just 200 men crossed the loch, in a boat that could only hold three men at a time, and as they gathered on the far side by the tree, he compared its ability to survive against the odds with their own. When Robert the Bruce finally won independence for Scotland after defeating the English at Bannockburn in 1314, many of his men wore sprigs of yew on their uniforms."

Amy Grimes/ Pavilion Books

Amy Grimes/ Pavilion BooksIn almost all cultures, the oak is used to represent strength – for example, says Hooper, "the Suffrage Oak was planted in Glasgow in 1918 to mark the Representation of the People Act passing into law – the first step in establishing votes for women in Great Britain". There are examples too of how trees have helped shape or symbolise ideas. The Wesley Beeches are a famous arch created by two intertwined beech trees in Lambeg, County Down: "They formed in 1787 when John Wesley, founder of the Methodist church, twisted two saplings together to demonstrate to his congregation the bond between Methodism and the Anglican Church of Ireland."

The folklore of nature and ideas around Paganism have been the subject of growing interest in recent years, with the New York Times even asking "Is the West becoming Pagan again?". The idea that nature can help heal us or somehow re-set our minds goes back to numerous ancient philosophies and religions that have long looked to our connection with nature. "The Buddha was a wild man," says the London Buddhist Centre on its website. "In the sense of being fully alive and responsive, attuned to nature in its deepest meaning. To reach towards this we humans need careful tending as much as a tree does, probably more."

In fact, the strength we can gain from nature and the resilience it teaches us are notions that are as old as philosophy itself. As John Sellars, author of The Fourfold Remedy: Epicurus and the Art of Happiness, among others, and Reader at Royal Holloway, University of London, tells BBC Culture, philosophy itself began as an attempt to understand nature: "Aristotle was a great biologist as well as a philosopher, and studied specimens – he was famous for dissecting fish and wanted to understand the different parts of an organism and how they function together in a biological way, and how that applies to humans." From Thales of Miletus and his 6th-Century peers to following generations, philosophers have long been fascinated by nature. "And many philosophers agreed with going back to nature and a simple life, away from the complexities of modern life, " adds Sellars.

The Stoics in particular "wanted to live in accordance with the natural world, in tune with nature," says Sellars. Roman Emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius wrote Meditations, in which he explored the idea that "anything that happens is the product of a natural process and part of how nature works – growth, life cycle, decay". He saw nature as a whole, and in this respect, according to Sellars, Aurelius might be seen as a precursor to the climate theorist James Lovelock and his Gaia theory, in which nature regulates itself. "Aurelius sees nature as an organism that regulates itself, and we're part of the larger organism. He saw our wellbeing tied up in nature as a whole." We are, in other words, part of nature and part of each other.

Aurelius wrote in the Meditations: "A branch cut off from the bough it belonged to cannot but be cut off also from the whole tree. Similarly a man, if severed from a single man, has fallen away from society as a whole." Sellars explains: "The tree is humanity, a human who is anti-social is a branch that has broken off (and so dies). We're all part of a single organism and we all depend on each other for our wellbeing."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo according to this idea, we are all dependent on each other: "Aurelius uses it as a metaphor for individuals in a community; every organism is dependent on the rest of nature. In modernity, isolated individuals can suffer poor health and mental health: none of us can survive alone, either physically or psychologically."

The inevitability of nature is also something that Aurelius considers in the Meditations: "What a fraction of infinite and gaping time has been assigned to every man; for very swiftly it vanishes in the eternal; and what a fraction of the whole of matter, and what a fraction of the whole of the life Spirit. On what a small clod, too, of the whole Earth you creep. Pondering all these things, imagine nothing to be great but this: to act as your own nature guides, to suffer what Universal Nature brings." It is interesting, says Sellars, that Marcus Aurelius is "hugely popular" at the moment. He is currently "the best-selling" philosopher, and there are "thriving communities" that follow his teachings.

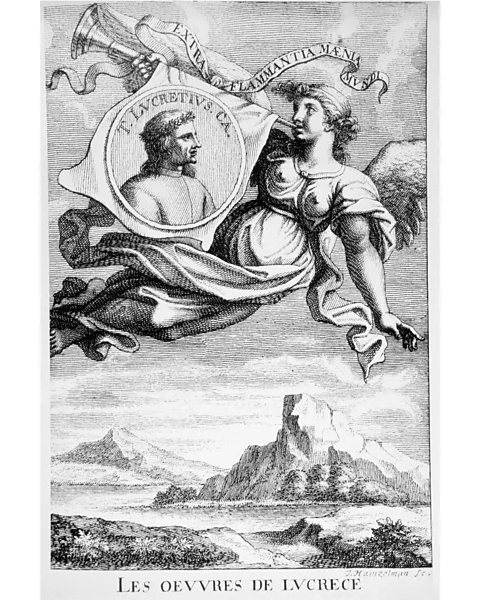

The Epicurian Roman poet Lucretius wrote about similar themes. "Lucretius wrote about the life cycles in nature, repetition, and the natural inevitable processes," says Sellars. Aurelius and Lucretius were helping their readers to accept their own mortality, and the fact that nothing lives forever. "The epic poetry of Lucretius and Aurelius share this idea that we should look at the big picture of nature, and that everything that exists is ultimately transient."

Both Aurelius the philosopher and Lucretius the poet, says Sellars, offer this "as a therapeutic idea, and that it puts everyday worries into perspective because of the bigger picture. Whatever everyday problems we may be wrapped up in, step back and see the bigger picture – within the large perspective, these problems are relatively insignificant."

We may not all feel the urge to re-locate to the wilderness, live off grid or completely re-wild our minds, but we can all find this sense of wonder and meaning in nature. Not only in our connection with it, but in the sense of hope and renewal it seems to offer us, each spring and summer. As Philip Larkin puts it in The Trees: "Last year is dead, they seem to say / Begin afresh, afresh, afresh."

Birdgirl by Mya-Rose Craig is published by Penguin on 30 June; The Great British Tree Biography: 50 legendary trees and the tales behind them by Mark Hooper is published by Pavilion Books; The Fourfold Remedy: Epicurus and the Art of Happiness by John Sellars is published by Penguin.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.