The sci-fi genre offering radical hope for living better

María Medem

María MedemIn these times of cynicism and despair, is 'hopepunk' the perfect antidote? David Robson explores radical optimism, and why it matters.

Alexandra Rowland didn't mean to spark a new artistic genre. In 2017, however, the fantasy author had a moment of inspiration. Rowland had been contemplating the rise of grimdark – the subgenre of fantasy fiction typified by George RR Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire (the inspiration for the TV series Game of Thrones) – which emphasises the flaws in human nature, and focuses on our capacity for cruelty.

But what could describe literature that instead focuses on our capacity for good? "The opposite of grimdark is hopepunk. Pass it on," wrote the author in a short post on Tumblr. The post soon went viral – and by 2019 the term had entered the Collins English Dictionary, defined as "a literary and artistic movement that celebrates the pursuit of positive aims in the face of adversity".

More like this:

Various works of fiction – including the Lord of the Rings and Terry Pratchett's Discworld series – have now been labelled as examples of hopepunk, along with a slew of contemporary writers.

"Cautionary tales are very important," says Becky Chambers, one of the leading authors associated with the hopepunk movement, who has won a much-coveted Hugo Award for her sci-fi Wayfarer series. "But if that is all that you have, you risk nihilism."

In the midst of current political, economic and environment uncertainty, many of us may have noticed a tendency to fall into cynicism and pessimism. Could hopepunk be the perfect antidote?

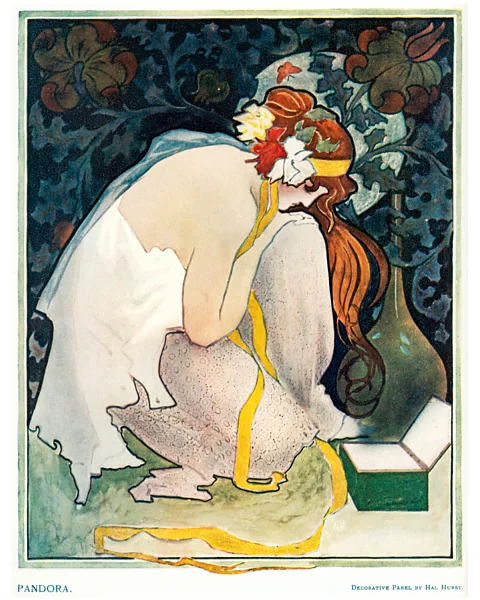

If you feel wary of optimism, you are far from alone. Writers and philosophers across human history have had ambivalent views of hope. These contradictory opinions can be seen in the often opposing interpretations of the Pandora myth, first recorded by Hesiod around 700 BC. In his poem Works and Days, Hesiod describes how Zeus created Pandora as a punishment to humanity, following Prometheus's theft of fire. She comes to humanity bearing a jar containing "countless plagues" – and, opening the lid, releases its evils to the world. "Only Hope remained there in an unbreakable home within the rim of the great jar," Hesiod tells us.

Alamy

AlamyThis is often interpreted as a metaphor for the emotion's potential to comfort us against the misery and duress that are inherent in the human condition. It sees hope as the sustaining force that Emily Dickinson would describe, thousands of years later, as the "thing with feathers – /that perches in the soul –".

It is possible to take a more pessimistic reading of the Pandora myth, however. Doesn't hope's presence in the jar, for example, suggest that it is some form of evil in itself? Perhaps Hesiod was hinting at the possibility that the supposedly soothing emotion can itself do harm.

The 19th-Century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was of this opinion. In Human, All Too Human (1878), he suggests that Pandora kept hope aside so that humanity would persist in living, despite the suffering that life inevitably entails. "Now man has the lucky jar in his house forever and thinks the world of the treasure. It is at his service; he reaches for it when he fancies it," he wrote. "Zeus did not want man to throw his life away, no matter how much the other evils might torment him, but rather to go on letting himself be tormented anew. To that end, he gives man hope. In truth, it is the most evil of evils because it prolongs man's torment."

Nietzsche's interpretation of the Pandora myth recalls Arthur Schopenhauer's descriptions of hope as "a folly of the heart". For him, hope is a delusion. In his essay Psychological Remarks (1851), he notes that the emotion "deranges the intellect's appreciation of probability" so that we neglect the likely outcomes of events, even when the odds are stacked against us. "A hopeless misfortune is like a quick death blow, whilst a hope that is always frustrated and constantly revived resembles a kind of slow death by prolonged torture."

The hopepunk rebellion

When explaining the origins of the term hopepunk, Rowland fully recognises the need to acknowledge human frailty and suffering – as seen in series like Game of Thrones. But they felt that it should be balanced with a recognition of our capacity to do good, and the possibility of positive change.

"Hopepunk says that kindness and softness doesn't equal weakness, and that in this world of brutal cynicism and nihilism, being kind is a political act. An act of rebellion," Rowland wrote in a follow-up to the original viral post. "It's about DEMANDING a better, kinder world." If hope sings a "tune without words" – as Dickinson described – then Rowland hears that song as a battle cry. This is the "punk" side of the moniker.

The essence of the hopepunk philosophy can be found in an exchange between Frodo and Samwise Gamgee in The Two Towers from Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films, as they struggle against the forces of evil around them.

"It's like in the great stories, Mr Frodo," Sam says. "Full of darkness and danger they were. And sometimes you didn't want to know the end. Because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end, it's only a passing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must pass. A new day will come. And when the Sun shines it will shine out the clearer."

"What are we holding on to, Sam?" Frodo then asks.

"That there's some good in this world, Mr Frodo... and it's worth fighting for," his friend replies.

Other novels linked to the genre include Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman's Good Omens, which tells the story of an angel and a demon joining forces to save the world from an apocalypse; and The Martian by Andy Weir, about an abandoned space explorer who uses his knowledge of botany to survive on the desolate surface of the fourth rock from the Sun.

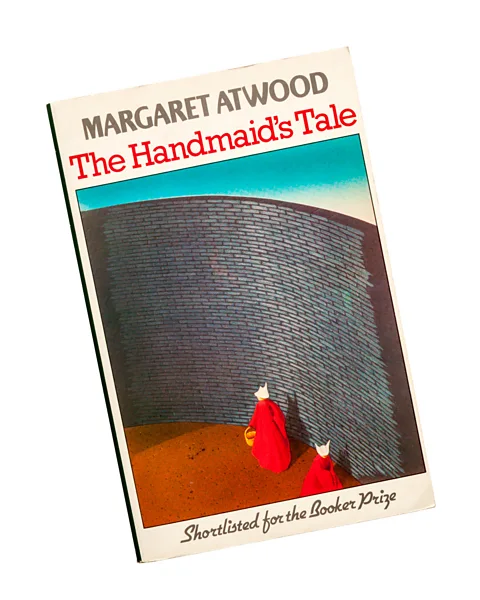

Alamy

AlamyPerhaps surprisingly, Rowland considers Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale to contain elements of hopepunk. The novel is usually regarded as a bitterly dystopian novel, but they point to the protagonist Offred's stubborn survival to keep fighting against oppression as an example of hope fuelling a fight for the greater good. (Atwood may not have used the term hopepunk herself, but she has spoken of her "qualified optimism" about our capacity to face environmental and political threats – which seems to chime with its general philosophy.)

More recent titles associated with the movement include Annalee Newitz's The Future of Another Timeline and The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison. Unsurprisingly, Rowland's own output reflects the hopepunk philosophy. The novel A Choir of Lies examines a nation on the brink of economic ruin. While the characters are flawed, and their mistakes are sometimes disastrous, they struggle to make amends for their actions – defying a fatalistic view of human fallibility.

The future is bright

For Becky Chambers, the aim is to create well rounded stories that represent the breadth of experience. "Everything cannot end well for everybody – because that that doesn't happen in real life," Chambers tells me. "But even when things go wrong, I take the time to show how these people heal."

A beautiful example of this can be found in Chambers's To Be Taught, If Fortunate, which details a crewed mission to exoplanets. Fifteen light-years away from Earth, they have to wrestle with feelings of loneliness and isolation from the rest of humanity, and the dangers of the hostile environments in which they find themselves. Yet they also find solace in each other and in their curiosity for the worlds they are exploring.

In one particularly memorable scene, the astronauts are stranded on the planet Opera, where their spacecraft soon becomes surrounded by a plague of scaly aliens that resemble a kind of slug-like rat. The planet's harsh weather system makes it impossible to move their craft – and the crew have to endure endless days and nights locked inside listening to the animals' "bone-chilling" cries from outside their craft.

The team never quite give in to despair, however, and the storm eventually eases enough for them to escape the planet – much to the surprise of the captain Elena. "She'd spent so much time focused on what could go wrong, she'd forgotten the possibility that something could go right," Chambers writes.

As someone who has suffered from depression, I couldn't help but feel it was a lesson in psychological resilience, and a reminder that our own internal storms will pass with time.

Chambers's Wayfarers series presents a grander vision of a fictional universe, with many different alien species forming the Galactic Commons. The societies that Chambers depicts are far from perfect – there are inevitable struggles and injustices – but the series nevertheless presents an optimistic vision of the space age, built on cooperation and empathy between beings of many different backgrounds. "I want the future to feel like something you could get excited about – and a place that we could consciously make if we chose to."

As we find ways to navigate our current crises – be they personal or political – we might all try to remember these lessons in looking for the light in the darkness. "Hope is something that is desperately needed," Chambers says. "And it's needed right now."

David Robson's latest book, The Expectation Effect: How Your Mindset Can Transform Your Life, is out now in the UK, and is published on 15 February 2022 in the US. He is @d_a_robson on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.