The ancient origins of the new nomads

Illustration by María Medem

Illustration by María MedemItinerant lifestyles may feel new but the ideas behind globe-trotting ways of living go back millennia. Cassidy George explores wanderings past and present.

One of the definitive movies of the year so far has been Chloé Zhao's Nomadland, which tells the story of a woman who decides to travel the US in her van after losing everything. Its exploration of nomadism as a means of reconnecting with nature and discovering the meaning of life struck a powerful chord, echoing a broader shift in mindset about the value of mobility. The film swept the awards season, and felt very much of the moment.

More like this:

The nomadic way of life has increased in popularity due largely to the rise of the digital nomad movement, driven by remote workers who are unbound by traditional office jobs. But interest in mobility has reached a peak in popular culture in the wake of the pandemic, a global health crisis that subjected us to long-term confinement, massive unemployment and the loss of loved ones. This convergence of crises has inspired many people to reimagine radically the very definition of a joyful, fulfilling life.

Alamy

AlamyA glance at social media confirms this shift in attitudes. Chesca Ford and Ben Birnie are two of the many individuals who have recently exchanged sedentary lifestyles in favour of more nomadic ways of being. In 2019 they decided they wanted to quit their jobs, abandon their permanent addresses, and pursue their shared dream of travelling full time. So they purchased a van, and spent the next few months converting it into their tiny home on wheels, which they lovingly call Sophia. Now they are digital nomads who roam Europe, documenting their forays into #vanlife, a hashtag that unites content created by people who travel or live in vans or RVs, with 10.3 million Instagram posts and 4.5 billion TikTok views. Their YouTube channel, Overlanding Sophia, has nearly 40,000 subscribers, and their videos have amassed more than five million views.

The couple discuss their nomadic lifestyle with BBC Culture over a video call, with Sophia's rear doors as the backdrop. "You don't need to finish university, get a nine-to-five job, get a mortgage, be stuck in one city for 15 to 20 years, and just wait it out until you retire," Birnie says. "You can have a happy, free life, and go where you want and do what you want, when you want to do it." Or, as Ford puts it: "There are alternatives to the script we've been fed."

Yet while the sudden broad interest in non-sedentary lifestyles does feel new, the ideas behind nomadic philosophies are ancient in origin. "The urge to migrate, to quest, to go on a journey, is deep-seated – ancestral, essential and instinctive," writes author Felix Marquardt, in his new book The New Nomads: How the Migration Movement is Making the World a Better Place. "Ninety-eight per cent of our time on Earth as anatomically modern humans has been spent as nomads. Living your whole life in the village, town or city of your birth is a relatively recent, anomalous development." Prior to roughly 12,000 years ago, people roamed the land in small, nomadic tribes, in search of edible vegetation and animals to hunt. Their movement patterns were dictated by and attuned with nature, shifting their location as they searched for fertile lands and retreated from storms and predators.

Overlanding Sophia

Overlanding SophiaThe development of agriculture and domestication of animals, known as the Neolithic Revolution, led to more permanent settlements, as humans swapped hunter-gathering for herding. Sedentary lifestyles and advancements in farming eventually gave way to major population growth, more centralised structures of power and the very concept of civilisation itself, which has long been linked to nation states in stationary geographic locations.

Free as a bird

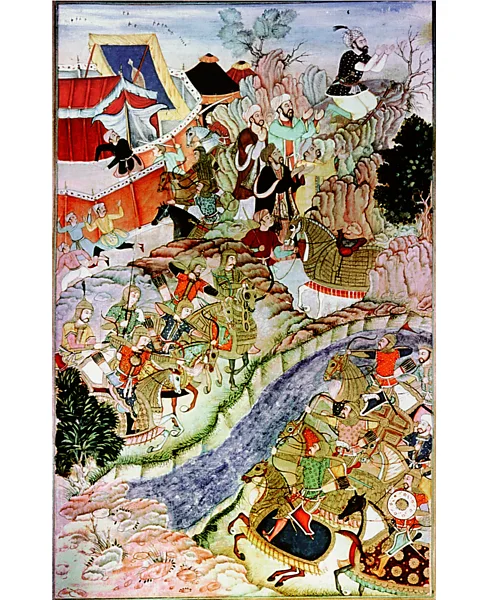

Certain populations maintained their nomadic lifestyles throughout history, and in some cases, to their tremendous benefit. The nomadic Scythians, who were documented by the Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th Century BC, were some of the most advanced equestrian warriors of classical antiquity. They were formidable opponents, with sophisticated weaponry. The Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg holds some artefacts from the era, including a gold belt plaque depicting Scythians with horses resting under a tree from the 4th to 3rd Century BC. The Scythians lived in wagons, and left behind no literature, furniture or houses. They were typically buried after death with small items such as drinking flasks and wooden bowls.

In the 12th Century, the Mongols gave rise to the largest land empire in history, with their conquered lands stretching from southern Russia and Ukraine to southern China and the borderlands in Mongolia, at its peak. "In most sedentary, agrarian-based empires with capital cities, the nomads were perceived as the rebel people, who were against state formation," says historian Marie Favereau, author of The Horde: How the Mongols Changed the World. Favereau's scholarship on ancient nomadic civilisations challenges bias against mobile communities in traditional history.

Hermitage Museum

Hermitage Museum"If you want to work on nomads, it's very challenging because you're using material and sources produced by sedentary actors at the time, who didn't understand them, and even feared them, because they have a very different relationship to the landscape and the notion of property," Favereau tells BBC Culture. "But these were extremely complex societies, who found political stability through mobility, and were very open to absorbing other cultures into their own."

This ancient prejudice, in which nomadic communities were perceived as inferior or less developed than sedentary ones, has led to centuries of discrimination with often violent consequences. Travelling groups such as the Romani were subject to ethnic cleansing in World War Two and, as recently as the 1970s and 80s in parts of Eastern Europe, forced sterilisation. In a phone interview, New Nomad author Marquardt comments on the transformation in public perception of the nomad's role in society. "Not that long ago, the nomad was basically the vagrant, the hobo, the gypsy, and all of the things that white people in Western Europe and North America were not too keen on. Now there's been a massive shift whereby nomadism has become the sort of ultimate status symbol."

There have long been romanticised narratives in literature and art, in which nomadic figures are often the protagonists. Many of our most influential narratives are stories of transience and travel, and the lessons reaped along the way. In Homer's Odyssey the eponymous hero Odysseus wanders for 10 years, as he tries to return home after the Trojan War to reassert his place as king of Ithaca. Reverence for the nomadic figure in the Romantic movement was rife, both in painting and poetry, and is honoured in Caspar David Freiderich's timeless painting, The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, which depicts a man atop a cliff, gazing over a vast sea. More recently, Bruce Chatwin's The Songlines, a travel book about Australian Aboriginal people, explores the human urge to wander. Not so romanticised is Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian in which a party of scalp hunters roam the US west in the mid-19th Century, with the American frontier depicted as brutalising for all.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRalph Waldo Emerson and his disciple Henry David Thoreau shared a transcendentalist philosophy, which celebrated man's connection with nature and the value of self-reliance, adventure and discovery. They promoted a transcendence of one's boundaries, and believed that society and its institutions were essentially corrupt, seeking instead isolation and nearness to nature. These ideas are still central to many US stories, in which the nomadic hero is reimagined as a cowboy, pioneer or Westward settler. Protagonists in film and fiction have frequently been portrayed as journeying in pursuit of "manifest destiny", a phrase, coined in 1845, to describe the notion that the US is destined (by God, according to the idea's advocates) to expand its dominion across the entire North American continent.

Twentieth-Century classics like Jon Krakauer's Into the Wild and Jack Kerouac's On the Road depict the nomad as the enlightened rebel who refuses to conform to urbanised life, and have cemented the wayward traveller's place in our conception of alternative culture. In Kerouac's Beatnik philosophy, there was a rejection of traditional family, a focus on individual liberty, and an opposition to mainstream society and institutions – ideas that were a precursor to the countercultural movements of the 1960s. On The Road is perhaps the quintessential example of Beat literature, embodying free-spirited non-conformity in a tale of road-trips across the US and Mexico. Discovering meaning through experience and wandering is at the book's centre, with the journey as manifestation of an inward search for meaning. In Kerouac's world, exploration and a hunger for life and new experiences are the key to liberation.

In Edward Abbey's Desert Solitaire, the 1968 manifesto of contemporary nomadic philosophy, the author famously renounces what he deems to be the insufferable characteristics of daily, urbanised life, like "the domestic routine (same old wife every night), the stupid and useless degrading jobs, the insufferable arrogance of elected officials, the crafty cheating and the slimy advertising of the business men, the tedious wars in which we kill our buddies instead of our real enemies back in the capital, the foul diseased and hideous cities and towns we live in, the constant petty tyranny of automatic washers and automobiles and TV machines and telephone!"

And although prejudice against those who live non-sedentary lifestyles continues to permeate the real world in Western culture, the romanticised idea of nomadism has increasingly come to be associated with minimalism, self-reliance, emancipation and self-discovery in 21st-Century popular culture. The idea of abandoning your home to pursue a life of adventure on the road, which may have felt like a pipe dream to prior generations, feels increasingly tangible and less drastic in the age of social media. Beth Johnstone, known on Instagram as @sheisthelostgirl, has lived as a nomad and #vanlifer for the past seven years. It's a way of life that feels accessible, she says, as people "come across new ideas and new ways to live" with the simple scroll of the thumb.

Getty Images

Getty Images"When I lived in my first vehicle, the 'van dwelling' lifestyle wasn't Instagrammable. It was seen as a kind of homelessness," Johnstone tells BBC Culture. "Now it has transitioned into the 'van life' label, which is seen as trendy and luxury, when the reality of cold outdoor showers, emptying portable toilets and waking up with ice on the windows is still very much the same." The aspirational quality of social media has highlighted the most cinematic aspects of contemporary nomadism, creating a conflation of jet-setting with the true philosophies and principles of nomadism. "It's not just about geographical nomadism," Marquardt says. "It's also about place, relatedness, community and education. Nomadism is about going beyond the familiar and embracing the other."

Pursuing a non-sedentary lifestyle is, in the words of Birnie, "not all sunshine and beaches". It also requires tremendous sacrifice, not only of material possessions, but, in many cases, of sustainable connections to community. But adopting a more nomadic philosophy and way of being doesn't always mean a total upheaval of your life, commitments and property. According to Marquardt, it doesn't even necessarily require physical travel. "Nomadism isn't just about adventuring to the other side of the world and discovering new places. There's also social nomadism or professional nomadism. Embracing nomadism could be as simple as inviting someone into your home that you don't necessarily know that well or agree with."

The root of the ancient philosophy of nomadism is not migration specifically, he argues, but rather the frame of mind required – an openness, curiosity, humility and willingness to embrace and explore new people, places and concepts. "When we move, we don't just learn about the place where we go," Marquardt says. "We also discover who we are and where we come from."

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.