Three ideas for how to live a fuller life

By reimagining our relationship with time – and coming to terms with death – we can improve our existence, argues Roman Krznaric.

“The word death is not pronounced in New York, in Paris, in London, because it burns the lips,” wrote the Mexican essayist and poet Octavio Paz in the 1950s. But for his fellow countryman – who talks about it and celebrates it in the annual Day of the Dead festival – “it is one of his favourite toys and his most steadfast love”.

This was probably an exaggeration, even back then, but it raises the question of the role that death plays in the art of living. Western culture has developed multiple mechanisms for shielding us from the reality of our mortality. The advertising industry tells us that we will remain forever young, we avoid speaking about death with our children, and we shunt the elderly away in care homes out of sight and out of mind.

Alamy

AlamyWe must learn to confront the terror of death and develop the courage to explore how awareness of our mortality can help us navigate the now. Just think of Frida Kahlo’s self-portrait Thinking About Death, which has a macabre skull plastered on her forehead. Or consider the pithy wisdom of Albert Camus: “Come to terms with death. Thereafter anything is possible.” But coming to terms with death is easier said than done. One of the secrets for doing so is not to spend hours contemplating visions of the Grim Reaper, but to reimagine our relationship with time itself. Here are three ideas for doing so that offer the unexpected prospect of existential sustenance.

Alamy

AlamyThe dinner party of the afterlife

In Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, a St Petersburg judicial prosecutor who has dedicated his career to rising through the legal ranks and helping his family achieve a respectable place in bourgeois society lies on his deathbed, aged just 45, wondering if he has wasted his life on superficial pursuits. “What if my whole life has really been wrong?” he reflects bitterly.

The story offers a useful thought experiment. If we project ourselves to the end of our life, when we are lying on our own deathbed, how would we feel about it looking back? Would we feel proud of our achievements? Would we feel that we had sucked the marrow from life? Or might we, like Ivan Ilyich, be filled with regret? The point, of course, is that such reflections can alter how we choose to act in the here and now. My favourite approach to making this temporal journey to the end of our lives is a visioning exercise I call ‘The dinner party of the afterlife’.

Imagine yourself at a dinner party in the afterlife. Also present are all the other ‘yous’ who you could have been if you had made different choices. The you who studied harder for exams. The you who walked out on your first job and followed your dream. The you who became an alcoholic, and another you who nearly died in a car accident. The you who put more time into making your marriage work.

You then look around at these alternative selves. Some of them are impressive, while others seem smug and annoying. A few make you feel inadequate and lazy. So which of them are you curious to meet and talk to? Which would you rather avoid? Which do you envy? Out of these many yous, is there one who you would rather be – or become?

Alamy

AlamyThe great chain of life

A second way to make sense of our existence is to draw on the wisdom of indigenous cultures whose worldviews dissolve the barriers between life and death, offering a sense of transcendence. There is an inspiring Māori concept known as whakapapa, which is their word for ‘lineage’ or ‘genealogy’. It is the idea that we are all connected in a great chain of life that links the present back to the generations of the past and forward to all the generations going on into the future.

It so happens that the light is shining on this moment, here and now, and the idea of whakapapa helps us shine the light more broadly, so we can see everyone throughout the landscape of time. It allows us to recognise that the living, the dead and the unborn are all here in the room with us. And we need to respect their interests as much as our own. Making this imaginative leap is challenging, especially for those of us immersed in a highly individualistic Western consumer culture.

But we can begin to do so with help from another thought experiment that involves journeying through time. Think of a child you know and care about – perhaps a godchild, a niece, or one of your own children or grandchildren. Now imagine them at their 90th birthday party, surrounded by family and friends. Picture their aged face, look at what is happening in the world outside the window. And now imagine someone comes over and places a tiny baby into their arms: it’s their first great-grandchild. They look into the baby’s eyes and ask themselves, “What would this child need to survive and thrive into the years and decades ahead?”

Sit with that thought for a moment. Then recognise that this tiny baby could be alive well into the 22nd Century. Their future isn’t science fiction. It’s an intimate family fact, just a couple of steps away from your own life. If we care about that baby’s life, we need to care about all life: all the people it will need for support; the air it will breathe; the whole web of life.

This kind of thought experiment can help us transcend the limits of our own lifespan and get in touch with the wisdom of whakapapa. We are all part of the great chain of life. And by recognising our place in it, we start extending our sense of what constitutes ‘the now’, shifting from a now of seconds and minutes and hours to a longer now of decades, centuries and even millennia. A now that gives us a sense of responsibility for the legacies we leave for the generations of tomorrow, while respecting the generations of the past.

Alamy

AlamyJourneys into deep time

We can also rethink our relationship with death by taking the perspective of ‘deep time,’ recognising that humankind, and our own lives, are just an eyeblink in the cosmic story. As the writer John McPhee put it, “Consider the Earth’s history as the old measure of the English yard, the distance from the king’s nose to the tip of his outstretched hand. One strike of a nail file on his middle finger erases human history.”

But remember, too, that just as there is deep time behind us, there is also deep time ahead. Any creatures that might still exist in five billion years when our sun dies will be as different from us as we are from the first single-celled bacteria.

Deep time enables us to grasp our destructive potential: in just two centuries of industrial civilisation, with our ecological blindness and deadly technologies, we have endangered a world that took billions of years to evolve. Don’t we have a responsibility to preserve the life-giving potential of the Earth for the generations to come? At the same time, situating ourselves in the grand expanse of time helps put our mortality in perspective. We are just a passing moment in a far bigger, longer narrative.

While deep time is elusive, its wonders are within our grasp. We can get there with the help of visionary science fiction writers like NK Jemisin or Ursula Le Guin, who enable our minds to travel across the aeons. Or try hunting for fossils, and holding a 200-million-year-old ammonite in your hand. Or gaze at stars whose light left their source before humans even evolved. Or make a pilgrimage to an ancient tree and, as novelist Richard Powers expressed it so beautifully, experience life “at the speed of wood”.

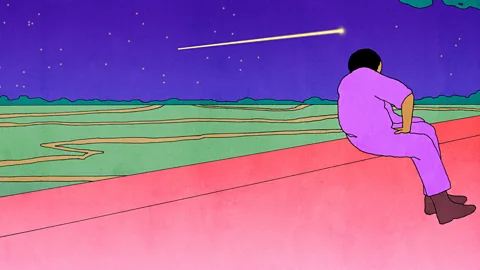

As we busily swipe our phones and click the ‘Buy Now’ button, let us pause a moment and open our imaginations to a longer now. That is how we begin the journey beyond death. That is how we become good ancestors.

Main illustration by María Medem

Roman Krznaric is a public philosopher. This article is based on his new book The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.