The clothes that shook the world

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe story of resistance fashion, from revolutionaries and Suffragettes to pink pussy hats and the ‘Bushwick Birkin’. Cath Pound explores clothing as rebellion.

For centuries, clothing has been armour for those who feel alienated from the mainstream, whether because of their views, gender, class, race or sexuality. From the red ‘Liberty’ cap worn by the sans-culottes in the French Revolution, to the ripped denim and slogan T-shirts of the hippies, and the pink pussy hat of the Women’s March, clothing has been used by marginalised groups as a tool of resistance, and in order to be seen and heard by those in authority.

More like this:

These are looks that have generally developed within popular movements, though in our politically tumultuous times they are increasingly appearing on the catwalk, inevitably leading to accusations of commodification. But a new exhibition at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York, which explores the manifold ways in which fashion can exert power, suggests the relationship is not always so simple. Resistance clothing can be fashionable, and the runway can be an effective tool of protest.

Getty Images

Getty Images“It’s always been in the interest of a movement to have a kind of visual cohesion,” says Emma McClendon, curator of Power Mode: The Force of Fashion, who cites the Suffragettes as an example. “They wore white to bring them together and provide a cohesive identity on marches.”

The white would often come in the form of a feminised version of the ultimate symbol of male civility, the suit. It was a sartorial demand for equality tempered by the purity of its colour, which emphasised that the women were still ideal citizens.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome more daring campaigners for equality even wore trousers, a practice that was illegal in many parts of the US and Europe. So strong was the association of trousers with patriarchal power that women didn’t truly gain popular acceptance wearing them until the 1960s.

The archetypal rebel look which still endures today is of course the leather biker jacket, jeans and white T-shirt combination which first gained traction in the 1950s, helped by the fact that “there was such a crossover between the resistance aspect and the pop culture aspect,” McClendon tells BBC Designed. However, she sees the Woodstock music festival in 1969 as the tipping point for resistance clothing becoming mainstream, and even fashionable, which inevitably produced tensions.

The Museum at FIT

The Museum at FITHippies “were using clothing very consciously like the Suffragettes or the sans-culottes as a tool of resistance,” says McClendon. The second-hand denim they wore which could be patched and embroidered as it wore down was “a political and visual protest against the shiny, plastic, space-age consumerism that was taking hold in the post-war period,” she says.

But, in the aftermath of Woodstock, Levis and Coca Cola began to use the look as a marketing tool. It became a style choice for those who had only a tenuous grasp of the hippies’ original ethos. Those who bought Tom Ford’s ripped and embroidered denim jeans for more than $3,000 in the late 1990s clearly had none. While that is a particularly egregious example of the commodification of resistance clothing it is by no means indictive of the fashion industry as a whole.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a pre-digital age, designers such as Katharine Hamnett and Patrick Kelly were clearly aware of the impact of using their collections to promote a message.

Hamnett famously wore a 58% Don’t Want Pershing t-shirt to a meeting with then-UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at Downing Street in 1984, while in the US Kelly, who died in 1990, used his label to engage with aspects of African-American identity. He designed leggings printed with a pattern resembling the African fabric, kente, and for his personal uniform chose denim dungarees, an allusion to the black sharecroppers of the US South. He was, like the Student Nonviolent Co-ordinating Committee during the Civil Rights Movement, reclaiming this symbol of subservience as a power statement.

Fight the power

Today, in a world where protestors are consciously aware that visual information is instantly sharable via social media “there is a gravitation towards these highly visible symbols much quicker than we saw in past movements,” says McClendon.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe references the black T-shirts of protesters in Hong Kong, the ‘gilets jaunes’ in France and, of course, the pink pussy hat, which has become one of the most potent symbols of resistance in the post-2016 landscape.

A month after the Women’s March, Missoni sent models wearing a version of the hat down the runway at the finale of their Milan Fashion Week show. Angela Missoni is known for being a long-term supporter of women’s rights and was undoubtedly aware that the image would have a huge impact. And as the hats were never produced commercially, there was no case of cashing in.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDior’s ‘We should all be feminists,’ T-shirt, which references the title of an essay by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and also became inextricably linked with the march, is a slightly more complex case. Created for the debut collection by Maria Grazia Chiuri, Dior’s first female creative director, it was intended to emphasise that the esteemed house was now designed by women for women. Retailing at almost US$800 (£612), it was never meant to be a protest T-shirt for the masses.

However, in the run up to the march, several celebrities posted images of themselves wearing it on Instagram. These posts received millions of hits, which effortlessly disseminated the message across the globe. In this way, argues McClendon, “it became a kind of rallying cry for the digital age and not just a commodification”.

There is no denying the impact a brand with the visibility of Dior is going to have, but McClendon acknowledges that “we tend to see more action and activity in the place of resistance from smaller independent labels.”

Maria Valentino/ Pyer Moss

Maria Valentino/ Pyer MossKerby Jean-Raymond’s brand Pyer Moss makes powerful statements about the racial prejudice evident even in his own industry. A black leather jacket with “We already have a black designer,” sprawled across it is a biting comment on tokenism. Elsewhere he references the forgotten history of the black cowboy by merging details like chaps with sneakers and tracksuits.

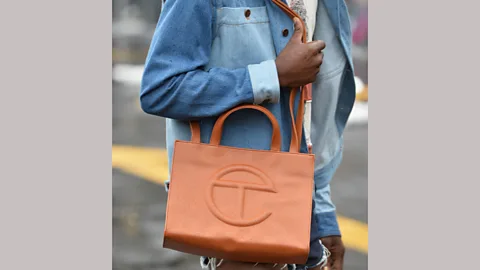

Telfar is another “really outspoken brand,” that consciously targets a “consumer base that is queer, of colour and just typically very marginalised and excluded from fashion,” says McClendon. Prices are also deliberately kept at an affordable level. A leather shopper bag nicknamed the Bushwick Birkin, after an area of Brooklyn, has gained huge popularity among queer and black consumers who are delighted that a brand actively recognises and celebrates them.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven more affordable is the jewellery created by British designers Tatty Devine. As active supporters of women’s and LGBTQ+ rights, the company has designed collections for anti-homophobia campaigns and in tandem with the Fawcett Society, Britain’s leading charity for gender equality.

It is clear people will continue to want to express their opposition to the status quo via what they wear. And while smaller brands are stepping up to the mark, McClendon says that the larger corporate-driven houses are going to have to acknowledge this new environment too.

“The industry can’t stay silent.”

Power Mode: The Force of Fashion is on at The Museum at FIT, New York, until 9 May.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List, a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.