Inside looksmaxxing, the extreme cosmetic social media trend

Alamy

AlamyOnline communities that present a dangerous view of male beauty are growing in popularity. When does a quest for self-improvement become something darker?

"I believe in taking care of myself, in a balanced diet and a rigorous exercise routine," says Patrick Bateman in American Psycho. The character – an investment banker who's also a serial killer – is played by Christian Bale in the 2000 film adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis's 1991 novel.

American Psycho is a satire of New York yuppie lifestyle in the 1980s, portraying a society dominated by hedonism, materialism and narcissism, according to the novel's author. "It's strange how that character has been co-opted into the culture in a way that he absolutely wasn't in 1991," Ellis told Publishers Weekly on the novel's 20th anniversary. "Patrick Bateman seems to embody something about masculinity that was blooming at a certain point in the late '80s to early '90s."

The film presents the main character's elaborate morning routine which, stripped of its wider satirical context, has become a tutorial for young men. The scene – featuring the unreliable narrator tying a plastic ice pack around his face and doing 1,000 crunches – has been watched 17 million times on YouTube and emulated in several #GetReadyWithMe (GRWM) shortform videos.

American Psycho has been the subject of numerous online debates, with the audience split between young men who are in on the parody and those who are decidedly not. In the latter group exists the internet looksmaxxing community.

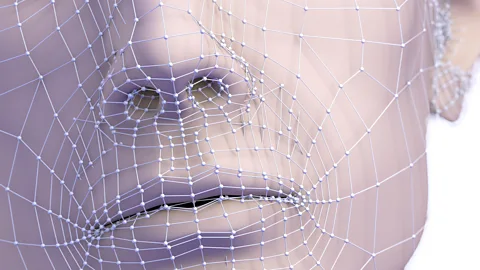

With roots in online incel (involuntarily celibate) forums, looksmaxxing claims to be about the "maximisation" of one's appearance. The aim of looksmaxxing is becoming the most attractive one can possibly look according to a set of prescribed criteria, with particular importance given to jawlines, eyes and physique (including "hunter" eyes, angled slightly upward toward the temples – a positive canthal tilt).

The trend has existed for at least a decade, but has recently been popularised and redefined on TikTok, where it's reaching a widening demographic of teenage boys algorithmically predisposed to the "manosphere" subculture. (Created in opposition to feminism, the manosphere refers to a network of websites and online communities propagandising masculinity and misogyny.)

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLooksmaxxing attaches "scores" to aspects of male appearance, focusing particularly on jawline, muscularity and skin. Looksmaxxers aim to increase their scores via "softmaxxing" (such as using a gua sha, burning more calories than consumed, or moisturising) and "hardmaxxing" (such as steroid use, hair transplants, or cosmetic surgery).

"It's really shocking," Dr Stuart Murray, director of the Eating Disorders Program at the University of Southern California, tells the BBC. "The TikTok stuff out there is not evidence-based, but it's reported as science."

Extreme makeover

Kareem Shami, 22, is both a victim and a leader of the looksmaxxing trend. Shami, who has 1.5 million TikTok followers, watched American Psycho at 18, right before his "transformation" (a form of makeover, a key part of TikTok looksmaxxing).

"There was something there that I didn't have, which was self-care," Shami tells the BBC. "I liked the movie, not because I could relate to a psychopath," he clarifies. "I didn't like the stuff he was doing." In 2012, Shami and his family fled the civil war in Syria. At his new school in Lebanon, he says his peers bullied him for his appearance.

At 18, Shami gave himself a makeover: complete with exercise, acne treatment, a new hairstyle and, of course, mewing – a technique of resting one's tongue against the roof of the mouth, in the hope that it would make jawlines more chiselled. Mewing was named after the controversial British orthodontist John Mew, who developed a practice called "orthotropics" and is the subject of new Netflix documentary Open Wide. The American Association of Orthodontists said in January that "scientific evidence supporting mewing's jawline-sculpting claims is as thin as dental floss".

After moving to the US to attend UC San Diego, Shami began posting looksmaxxing content on TikTok, under the "glow up" category of videos. On social media, "glowing up" refers to conventional transformations, typically involving a significant makeover in appearance. There are communities online that offer spaces to share one's "progress", whether it comes to clearing acne, losing weight, building muscle or just going through puberty.

Getty Images

Getty Images"As a young person in Syria, I lost control. I live my life with the idea that I strive towards stability," says Shami. The vast majority of his TikTok demographic is male, between the ages of 17 and 23, he says.

Shami runs an online course that offers lessons on how to "master the art of facial aesthetics". In this course, and in looksmaxxing generally, there is an emphasis on numbers. On some forums, users who submit selfies receive a crowdsourced score based on how their appearance fits within a certain scale. Dr Murray says rigidity around numbers is often characteristic of eating disorder communities.

Murray specialises in researching the particularities of male eating disorders. Muscle dysmorphia is an eating disorder that is often overlooked and dismissed by medical professionals, Murray says. Muscularity-oriented disordered eating in males has been present for decades, originating from the Arnold Schwarzenegger era in the 1980s and fuelled by media representations of muscularity as desirable and attainable through dietary restriction and steroid use. Whether it's cutting or gains season (fitness terms that originally applied to bodybuilding, meaning dieting and muscle-gaining phases) for those in the looksmaxxing community, the constant fluctuation of body composition can be harmful.

Vulnerable young girls and boys who grow up on social media are especially susceptible to self-commodification and an obsession with appearance. That mental framing is innately harmful, encouraging the internalisation of unattainable beauty ideals, which can lead to dissatisfaction with body weight and shape.

Often referenced in the looksmaxxing community, bodybuilder and YouTuber Aziz Sergeyevich Shavershian, or Zyzz, was a proponent of muscular enlargement, with his followers dubbed "the Aesthetics Crew". Shavershian died of a heart attack at the age of 22, in 2011. A post-mortem examination revealed that Shavershian had an undiagnosed heart condition that triggered cardiac arrest, according to Shavershian's mother.

Visual inspirations for looksmaxxers also include male models Jordan Barrett, Sean O'Pry and Francisco Lachowski. Creators online recreate their poses, or caricature the models and Patrick Bateman by donning a smize and a Zoolander pout (a "sigma face") as part of the "sigma male" trend.

But Shami was never warmly welcomed to the original looksmaxxing community. Around the cusp of his adulthood, his likeness "blew up" on social media, after users uploaded his before and after photos on what he calls a "toxic, black-pilled" looksmaxxing forum. "Pill" references online allude to the red pill in the film The Matrix, in which Neo is presented with a choice: witness the world the way it "really" is by taking the red pill or remain ignorant by taking the blue pill. The red pill represents an awakening, mainly drawing online users towards conspiratorial ideation or fringe political identification. The black pill represents a defeatist belief that the system is too far gone to change.

"I hadn't known of the term 'looksmaxxing' until I was posted on their forums, where users were hating on me and asking whether or not I had surgery for my transformation," Shami says. "Some people hated me because I was spreading how to improve yourself."

For critics who argue that looksmaxxing perpetuates unrealistic physical expectations, prompting disordered eating habits among teenage boys, Shami pushes back. If adults really took issue with unrealistic expectations online, he argues they should include the make-up industry, which has been targeting women and girls on social media for years. Although, clearly, criticising looksmaxxing is not the same as ignoring issues with the make-up industry.

Online "guides for improvement" range from the helpful (basic hygiene tips) to harmful (spreading racism, sexism and body dysmorphia). To navigate the continuum, Dr Murray recommends that parents review content with their children.

But the self-objectification of looksmaxxing is itself inherently dangerous, argues Dr Murray, encouraging young men to evaluate themselves based on weight or perceived attractiveness. Eating disorders in young men can be masked by muscle bulking and over-exercising.

Treatments for eating disorders include therapy, medical supervision and medications. Whether the patient suffering from disordered eating is female or male, the treatment must centre on "generating weight restoration", says Dr Murray. "For boys and men, there are additional barriers in treatment with the construction of masculinity," says Dr Murray.

Dr Murray warns that behind the apparent self-improvement of looksmaxxing, there's a core message that could lead to psychological damage. "If we fall into the trap of dissatisfaction and low self-esteem, if you're diluting yourself down to a number or a skin tone, or an angular tilt of your face, it reduces your value as a person. We want men to focus on more sustainable ways to generate their self-esteem and identity."

Details of help and support for audiences in the UK are available at www.bbc.co.uk/actionline.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.