The Jane Austen novel you don’t know

Alamy

AlamyEven Jane Austen devotees often haven’t read her final – and unfinished – novel. But ever since Austen’s death 200 years ago, many writers have taken it upon themselves to complete.

Jane Austen put down her pen as a novelist on 18 March 1817. She was working on a comedy which skewered a new health fad at emergent English seaside resorts – ‘taking the waters’, as it was known. The book, Sanditon, halts partway through chapter 12 with an abruptness that suggests ill health was to blame rather than any artistic misgivings. Four months later, Austen died.

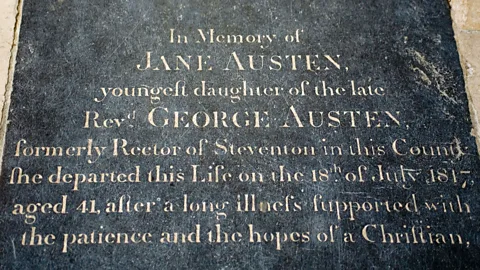

In a letter just five days after she stopped working on Sanditon , Austen wrote of having been “very poorly” with an assortment of ailments including fevers. “Sickness is a dangerous Indulgence at my time of Life”, she chides herself, bravely wry at age 41. (Though her tombstone alludes to a “long illness supported with the patience and the hopes of a Christian”, her cause of death remains a mystery, despite the sleuthing efforts of several present-day physician fans.)

The manuscript consists of around 23,500 words written over the course of seven weeks. It focuses on a tirelessly – and tiresomely – enterprising landowner named Mr Parker, who is determined to transform the village of Sanditon into a popular watering hole like Brighton. To do so, he needs the assistance of his neighbour, the wealthy but only superficially generous Lady Denham. Lady Denham is trailed by would-be beneficiaries of varying levels of obsequiousness. Charlotte Heywood, unmarried and keen-eyed, is the outsider that Austen ushers into their midst.

You might also like:

• The racy side of Jane Austen

The manuscript’s final sentence tidily skewers pomposity and the male ego. It acknowledges the fates of Lady Denham’s two late husbands; their portraits have been hung to stare at each other across her sitting room, one from a distinctly preferential patch of wall. “Poor Mr. Hollis! - It was impossible not to feel him hardly used; to be obliged to stand back in his own House and see the best place by the fire constantly occupied by Sir H. D”, Austen writes. With that, the novel falls silent.

Or at least, the novel as envisaged by Austen falls silent – because two centuries on, fresh versions of Sanditon are still being generated. The manuscript’s incompleteness is vexing and tantalising in equal measure. There’s just enough to give a flavour of what might have followed without yielding any substantial clues. Austen left no notes and didn’t even title the work. But a succession of devotees has interpreted its open-endedness as an irresistible challenge, taking it upon themselves to pick up where Austen left off.

In the years since the ink dried on that final full stop, at least seven such efforts have made it into print, beginning with a version by Austen’s niece, Anne Austen Lefroy. Lefroy’s attempt ought to be the most persuasive – Austen quite possibly discussed the plot with her – but is itself incomplete.

Alamy

AlamyMost writers who fully ‘complete’ the novel, on the other hand, abandon the manuscript’s comic aspects and take it in a realist direction. They also add new characters in an effort to ignite the romance that a large section of her fanbase prizes most. In 1932, Alice Cobbett’s Somehow Lengthened threw in some shipwrecks and smugglers for good measure. In 2008, A Cure for All Diseases, part of Reginald Hill’s Dalziel and Pascoe series, was billed as a completion of Sanditon, its backdrop renamed Sandytown and moved to Yorkshire.

With the advent of online fan fiction, these continuations have proliferated – and grown nuttier. A generous reading would be that the ardour these writers have for Austen, or for their own invariably romanticised version of her, is so mighty that it eclipses any sense of their own literary limitations.

“Some authors try to recreate Austen’s prose, which usually falls flat if you’re looking for Austen. But I don’t think you should look for Austen. The continuations make the case for adaptation and imitation as a different mode of writing,” says Kathleen James-Cavan, an Austen expert based at the University of Saskatchewan.

James-Cavan recently delivered a paper at a Sanditon conference hosted by Cambridge University. Her topic was Welcome to Sanditon – a vlog spin-off of the Emmy-winning web series The Lizzie Bennett Diaries, in which Georgiana Darcy replaces Charlotte and is tasked with beta-testing a new social media app on the residents of Sanditon. Though the vlog lasted just three short months in 2013, it got very meta. “I thought it was rather lovely the way art meets life there. What interested me is the satire of entrepreneurship, in the original and 200 years later,” says James-Cavan. What would Austen herself have made of it? “I think she would have had a hoot and then asked for royalties, rightly so.”

Still, works begun by one author and finished by another can’t help but pose interesting ethical as well as critical challenges. When an author has died by the time of publication, it can become genuinely problematic. Austen may never have intended to publish Sanditon, for example. Jan Todd, a renowned scholar of early women authors, isn’t certain. “Austen is a writer who wrote, corrected and rewrote – after all, Pride and Prejudice took years to perfect. And Sanditon must be a first draft,” she says. “Maybe it wasn’t even intended for publication – at least not in the short run. After all she had two unpublished, possibly finished, manuscripts by her at the time.”

For James-Cavan, the manuscript itself provides the biggest clue. A copy is on display at Brighton’s Royal Pavilion until January 2018 as part of a small but enlightening exhibition that sets Sanditon in context of the seaside tourist boom and paints the Pavilion’s creator, King George IV, as something of a fan-boy: he kept a full set of her novels in each of his palaces. (Austen dedicated Emma to him in 1815, even though she disapproved of his antics as Prince Regent.) The manuscript was diligently copied from the original by Austen’s sister Cassandra, whose neat, slanting script recalls Austen’s own and provides a jolting reminder of the intimacy of handwriting – something we see less and less of. And yet it’s missing a vital feature of the original: the many blank pages that Austen left in her draft. “There was either an intention to complete the whole text or for someone else to complete it. She was using up lots of paper, which was expensive,” James-Cavan says.

Alamy

AlamyIt wasn’t until 1925 that Sanditon reached the reading public. Initially, Austen’s family felt that the chapters, together with a comic poem written three days before the author’s death, were embarrassing and would detract from her reputation. “Both were considered unseemly,” notes Todd. That sense of embarrassment on Austen’s behalf was shared by subsequent generations of admirers, whose first source of information after the novels themselves was invariably the biography written by her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, which depicted her in a very particular light.

When it was finally published, Sanditon’s reception was mixed. EM Forster was far from convinced of its merits, and critical opinion remains divided. But different though it is from Austen’s best loved works, the manuscript is of a piece with the comic prose and poetic skits that she developed in her teenage works, and that she continued to compose even while writing her most mature fiction.

“She enjoyed the wacky and slightly surreal,” Todd says. “If you want Austen to continue perfecting her methods of psychological realism and inner discourse – in the way Virginia Woolf admired – then Sanditon appears a sad falling off in style and method. The changes to the manuscript often aim to exaggerate rather than tone down and make subtler. I love Sanditon both for its funny elements and for the way it catches something of the cultural life of England following the end of the long Napoleonic Wars.”

Alamy

AlamySanditon has remained in print ever since. Along with its timeless humour at the expense of entrepreneurs, it satirises quackery and hypochondria – both equally enduring aspects of life, and the latter a poignant, if escapist, theme for an author who must have suspected her own body was failing. “The mockery in Sanditon of the health industry and the fuss we all make about diet and drink is appropriate even more to our own age than to Austen’s,” notes Todd.

But as we mark the 200th anniversary of Austen’s death, it’s the manuscript’s very imperfections that are perhaps its greatest contribution to our quest for a fuller understanding of her. As James-Cavan says, “The family was very keen to produce an image of Good Aunt Jane, the pious spinster – words her brother and nephew used about her. There was a keen interest in creating an image of a nice Christian lady. She was that but she was also a wit.” And a devilish one at that.

But as ever, Austen puts it best herself. As she confided in a letter to her niece, Fanny Knight, written a week after abandoning Sanditon: “Pictures of perfection as you know make me sick & wicked”.

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.