The ancient place where history began

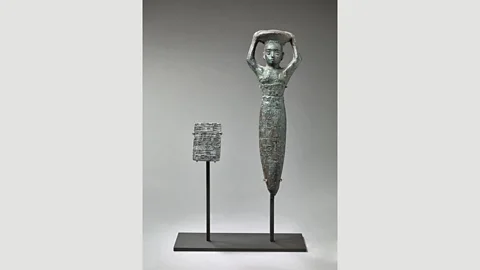

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Stéphane Olivier

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Stéphane OlivierThe idea of Mesopotamia has intoxicated the West for centuries. Alastair Sooke takes a look at a civilisation where much of modern culture took form.

“Everybody has heard of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Tower of Babel, Nebuchadnezzar, and the Flood,” says Ariane Thomas, a curator in the Middle Eastern antiquities department of the Louvre. “So, you see, Mesopotamia is much more familiar than people think.”

We are standing at the threshold of History Begins in Mesopotamia, a new exhibition of almost 500 objects at the Louvre’s outpost in the northern French town of Lens. Spanning 3,000 years of Mesopotamian history (an area that roughly corresponds with modern-day Iraq), it begins with the invention of writing, in the late 4th millennium BC, and ends in 331BC, with Alexander the Great’s conquest of Babylon.

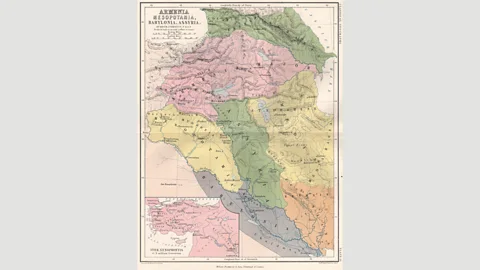

Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock PhotoThere are many fascinating historical artefacts as well as magnificent works of art, such as an alabaster statue, from around 2250BC, of a seated official, wearing an elaborate fleece skirt, with a beard, shaved head, and stunning blue inlaid eyes of lapis lazuli.

The first gallery marks Mesopotamia’s ‘rediscovery’ in the 19th Century, when archaeologists began excavating in the Middle East. They were intent on discovering more about the late Assyrian and Babylonian empires of Mesopotamia, which, at that point, were chiefly remembered through references in the Bible and classical texts.

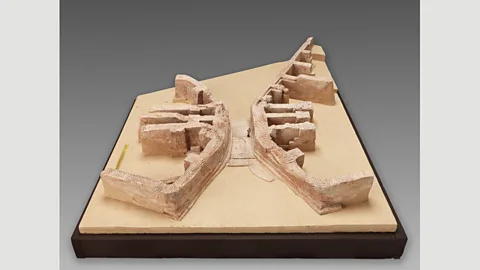

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Raphaël Chipault

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Raphaël ChipaultNot only did they locate the ancient Assyrian capital of Khorsabad, a few miles north-east of Mosul in northern Iraq, but they also discovered the forgotten civilisation of the Sumerians, who once dominated the south of the land.

Quickly, the idea of Mesopotamia intoxicated the West. “It captured the European imagination because people saw imperial powers expressed in the imagery, which they could relate to,” explains Paul Collins of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, whose new book, Mountains and Lowlands: Ancient Iran and Mesopotamia, was published last month.

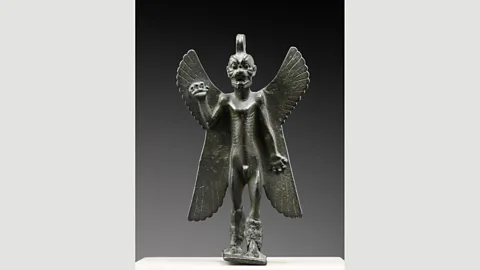

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Philippe Fuzeau

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Philippe Fuzeau“Also, of course, it seemed to illuminate the world of the Bible, so there was a sense of a world which was alien and exotic, but also with these fundamental characteristics that were familiar: empires, cities, kings.”

A video projection in the second gallery of the Lens exhibition reveals the extent to which what we might call ‘Mesopotamia-mania’ has infiltrated our own culture.

The ‘land between rivers’

By the 20th Century, Mesopotamia was a touchstone for everyone from artists and architects (witness the decoration on the Fred F French Building, an Art Deco skyscraper in New York), to advertisers and film-makers (consider the starring role played by the Mesopotamian demon Pazuzu in 1973’s horror film The Exorcist). Today, Mesopotamia has been given a fresh lease of life within popular culture, thanks to the success of the Civilisation video games and the prominence of Pazuzu in the Marvel Comics universe.

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Thierry Ollivier

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Thierry OllivierGiven this profusion of references, it is tempting to ask whether the ancient civilisations of this enormous region, which corresponds to most of Iraq but also encompasses parts of Syria and Turkey, shaped our world in a more fundamental sense, too. As Monty Python might have put it, what did the Mesopotamians do for us?

The answer, it turns out, is quite a lot. But before getting into the nitty-gritty, it’s important to understand what we mean by Mesopotamia. It was the ancient Greeks who coined the term, which means ‘the land between rivers’. They were referring to the flat alluvial region in between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, the so-called ‘cradle of civilisation’ where men first left behind a way of life as hunter-gatherers and founded more settled societies based upon agriculture, which were flourishing by 6000BC.

B O'Kane / Alamy Stock Photo

B O'Kane / Alamy Stock PhotoAt some point in antiquity, in the land of Sumer (modern-day Iraq and Kuwait), irrigation was invented as a way of exploiting the fertile earth of southern Mesopotamia. To organise the network of irrigation channels and canals, an administrative system was established that in time stimulated the rise of first city-states, such as Uruk, then kingdoms, and eventually empires.

What linked the various phases of Mesopotamia’s long history was a shared set of customs, traditions, myths and legends, and religious beliefs – in other words, a distinct, and sophisticated culture. Following the invention, around 3200BC, by the Sumerians of the cuneiform script – a system of writing that derives its name from the Latin word cuneus (wedge), a reference to the distinctive shapes of the signs that scribes impressed with a stylus into soft clay tablets that were then dried in the sun – these customs and beliefs were preserved in written texts. Many official tablets were also stamped with cylinder seals, another distinctively Mesopotamian piece of technology.

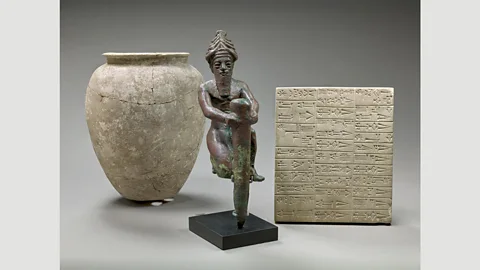

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Raphaël Chipault et Benjamin Soligny

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Raphaël Chipault et Benjamin Soligny“The idea of Mesopotamia is based on the notion of writing,” explains Collins. “It’s this sense that we can connect 3,000 years through the written text. There were scribes and bureaucrats who maintained the tradition, despite the rise and fall of empires, and the arrival of new people and ideas. Mesopotamia is like a sponge. Whenever new people arrive in the region, they absorb the long traditions of Mesopotamia. We see a lot of continuity in terms of religious beliefs and administrative practices.”

Melting pot

Since Mesopotamia is so old, it boasts a lot of ‘firsts’. Archaeologists point to technical inventions, such as the potter’s wheel, as well as remarkable progress in mathematics, medicine and astronomy. The way that we count time, dividing up each hour into 60 minutes, is something we have inherited from the Mesopotamians. Even the first attested consumption of beer comes from Mesopotamia, where dairy and weaving were also developed.

Musée du Louvre/Raphaël Chipault et Benjamin Soligny

Musée du Louvre/Raphaël Chipault et Benjamin SolignyAccording to Ariane Thomas, Mesopotamia’s location was an important factor in its success, which was underpinned by an enormously rich agricultural base. “Mesopotamia was right at the centre of the Middle East,” she explains. “While its dry earth proved very fertile with irrigation, it also had to be open to the outside, because it lacked important resources, including some woods, stones and metals.” This meant that Mesopotamian civilisations were outward-looking and dynamic.

In his new book, Paul Collins traces the interaction between Mesopotamia and the peoples of the highlands of present-day Iran. The Zagros Mountains were rich copper, which could be used for tools and weapons, as well as lead, silver and gold. “The great monuments of Mesopotamia were often made from or decorated with materials that came from Iran,” Collins explains, referring to the mud-brick ziggurats, several stories high, that characterised Mesopotamian cities (especially Babylon), and inspired the Tower of Babel. (Sadly, in recent years the so-called Islamic State has done irrevocable damage to many important Mesopotamian monuments and sites.)

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumYet Collins believes that simply listing the inventions of the Mesopotamians can result in a distorted view of history. “The Sumerians are always credited with the invention of everything,” he says dismissively. Instead, he says, archaeologists now find it more valuable to concentrate on the “forces” that influenced Mesopotamia from the outside.

“Mesopotamia was a melting pot, with a mixed population,” he explains. “People spoke different languages and presumably had different underlying cultural traditions. So often, people think simplistically about ‘the Sumerians’ or ‘the Assyrians’, when of course we’re talking about a much more complex society.”

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Martine Beck-Coppola

RMN-Grand Palais / Musée du Louvre / Martine Beck-CoppolaFor Collins, Mesopotamia’s most important contribution to the modern world is the city, where all this dynamic interaction could take place. “Over several centuries, we see the development of massive urban centres, with thousands of people living together,” he says. “Quite what’s driving them to come together we can’t yet tell. There are all sorts of possible factors, such as the environment, or the need to manage resources. Ultimately we could be talking about significant individuals who compelled or encouraged people to support them. So, the same sort of factors we see in modern politics could underlie the rather broad-brush things we see in archaeology.”

He continues: “But once cities are established, they never stop. Mesopotamia provides the earliest evidence we have for people grappling with many of the questions for which we are still coming up with solutions today. How do you manage large numbers of people living together? How do you feed them? How do you deal with overpopulation? And what technology – such as the administrative tools of writing and cylinder seals – allows you to create hierarchies and meaning in a society, so that there’s a sense of collective identity? That’s why cities, in the sense that we think of them now, are Mesopotamia’s greatest legacy.”

Alastair Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.