The myths and folktales behind Harry Potter

Warner Bros

Warner BrosNicolas Flamel was a real person, and many of Rowling’s fantastic beasts she borrowed from elsewhere – including from the ancient world, writes Natalie Haynes.

If the trailers are anything to go by, we already know where to find fantastic beasts: Eddie Redmayne has a suitcase full of them in 1926 New York. But where did they come from, the dragons, unicorns and hippogriffs of the Harry Potter universe? Monsters and mythical beasts perform a role in JK Rowling’s work which transcends that of world-building: they add symbolic and psychological depth, as well as reminding us that we are visiting a magical place. Rowling is both an inventor and archivist of fantastical animals, populating her universe with a mixture of what one might term ‘classic monsters’ (trolls, centaurs, mer-people) and folklore staples (bowtruckles, erklings), alongside her own inventions (dementors).

Warner Bros

Warner BrosSome of these collected monsters are vastly better known than others: grindylows and boggarts, for example, have origins in Celtic and English folklore, but they are hardly household names. These relatively minor creatures often have a less-than-fantastical backstory: grindylows live in shallow water and threaten to grab at children with their green, reed-like arms. It isn’t difficult to see here both an explanation for the existence of the grindylow – it shares many characteristics with water plants, which are usually mobile and thus have their own disquieting appearance – and an explanation for why such stories might thrive – as a warning from parents to their children to keep away from a potential hazard, even if the risk was more likely to come from drowning than a malevolent water sprite.

But the vast majority of Rowling’s best-loved monsters have winged their way from the Ancient World to her modern, magical one. Fawkes the Phoenix is not only a fantastic beast, capable of auto-regeneration, he’s also a historical one. His colouring – red and gold – is the same as that of the phoenixes mentioned by Herodotus in his Histories from the Fifth Century BCE. Herodotus is known as the ‘father of history’ and, by his critics, as the ‘father of lies’. He reports what he is told by people he meets on his travels, often without the presentation of further evidence. In this instance, he’s told that phoenixes live in Egypt, so he relays this information to his readers. He does add that he hasn’t seen the creature himself, only pictures of one.

Even the more critical Roman historian, Tacitus, reports on a phoenix-sighting, again in Egypt, during the reign of the emperor Tiberius in the First Century CE. Tacitus found some disagreement about the bird’s lifespan, but says it is generally held to live for around 500 years. His sources are unanimous on the subject of the bird’s beak and the colour of its plumage, however: all agree that it differs from every other bird, and is sacred to the sun. Interestingly, Tacitus and Herodotus suggest not that a phoenix is reborn from its own flames, but that a young phoenix will carry the body of its parent bird some considerable distance and then bury it. Though even as he tells us the story, Herodotus describes this particular element as ou pista – unbelievable.

Another Harry Potter animal who has undergone changes to his fantastical nature is the multi-headed dog. Cerberus, the dog who guards the entrance to the Underworld in Greek myth, is a dog of many talents but no fixed number of heads. The poet Hesiod reckoned he was a 50-headed beast, and Pindar was more ambitious still, suggesting a hundred heads. Later Greek and Roman writers usually go for three, although vase painters – there’s a beautiful example of Cerberus on a vase in the Louvre – often depict him with two. Perhaps two heads are better than three, when it comes to painting them. However many heads he has, Cerberus has one thing in common with Fluffy, the three-headed dog in the first Harry Potter novel: both are distracted by music.

DeAgostini/Getty Images

DeAgostini/Getty ImagesCerberus is a discerning dog, and it takes the lyre-playing of no less a musician than Orpheus to paralyse him (as Virgil tells us in The Georgics), holding his three mouths agape. Fluffy is an easier audience, and can be lulled to sleep by a mere enchanted harp. In a nod to the Cerberus myth, Rowling employs Fluffy as a guard-dog, lying atop the trapdoor which leads Harry, Ron and Hermione on their search for the philosopher’s stone. Are we meant to wonder if the children are entering the gates of hell? Certainly they undergo trials which wouldn’t be out of place in the underworld of Greek myth: the torturous puzzles, the physical peril, the emotional trauma.

Global mythmaking

The philosopher’s stone itself has its roots in both myth and history: Dumbledore’s friend and the stone’s inventor, Nicolas Flamel, was a real scribe who lived in Paris in the 14th Century. Many years after Flamel’s death, he was said to have discovered the secret to eternal life: later writers attributed alchemical skills to him but there is no evidence to suggest he actually possessed these. Nonetheless, he has a street named after him in Paris today (as does his wife Pernelle), which is a kind of immortality, at least.

SSPL/Getty Images

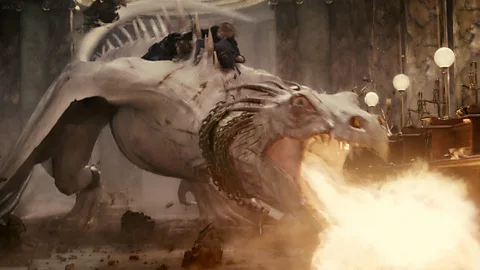

SSPL/Getty ImagesEven dragons – who have twin mythic histories in Europe and Asia, as Rowling observes with the shorter snout and protuberant eyes of her Chinese Fireball dragon – take their name from the Greek word, drakon. And the basilisk which dwells inside the Chamber of Secrets has also taken his name from the Greek: a diminutive form, meaning ‘little king’. Rowling kept the part of the basilisk myth which sees it capable of destroying everything in its path with its toxic force. Happily for her readers, she abandoned the fatal flaw which is detailed by Pliny the Elder in his Natural Histories: for Pliny, the basilisk can be destroyed by the mere smell of a weasel.

Warner Bros

Warner BrosPerhaps the most enigmatic monsters at Hogwarts are the centaurs who live in the forbidden forest. They seem to be direct descendants of the centaurs which were believed to have lived on Mount Pelion in Thessaly, in central Greece. Rowling’s centaurs also preferred a woodland home, although they had a reputation for lascivious behaviour which the noble Firenze and his companions have avoided. Firenze himself, with his passion for astrology and education, owes something to the celebrated centaur, Chiron, who was teacher to Achilles, Theseus and other Greek heroes, and was also a renowned astrologer. There is a beautiful fresco, originally from Herculaneum, in the archaeological museum in Naples, which shows Chiron teaching Achilles to play the lyre. His back legs are curled behind him, almost like a dog, while his front legs support his weight and his hands pluck at the lyre strings. It’s a beautiful reminder that human beings have been thinking of mythical beasts for as long as we have been writing, painting and thinking.

Magic and metaphor

Beasts made up of two species – centaurs, mer-people – are a common part of folklore. But even more complex species-mingling occurs sometimes. The hippogriff is a relatively modern creation, dating back to an Italian poem of the early 16th Century. But the combination of griffin (itself a combination of an eagle and a lion) and horse is predicted centuries earlier. In his Eclogues, Virgil describes a scene in which all the usual rules no longer apply: griffins will mate with mares, he says, and fearful deer will drink next to hounds. The very existence of a hippogriff is presented as an impossibility, not because of their fantastical nature, but because of the well-known animosity (to Virgil’s audience, at least) that existed between horses and griffins.

DeAgostini/Getty Images

DeAgostini/Getty ImagesOne interesting point is to consider the monsters and beasts which Rowling has not used, most notably the satyrs and nymphs which populate so much Greek myth. (The French witch Fleur mentions that wood nymphs are used as Christmas decorations at the Beauxbatons school, but they seem to have no other role). It’s this as much as anything that makes us think about the symbolic purpose of the mythic creatures in Harry Potter. Harry’s world – perhaps surprisingly for one filled with teenagers – is largely devoid of sex: there is some kissing, but the predation which satyrs represent is absent. Even the girl who shares a name with the passive Greek nymphs, Nymphadora Tonks, shares little else with them, besides an ability to change appearance (and usually when this happens to a nymph, it is because she is trying to avoid a lusty satyr, rather than battle evil).

Other creatures serve allegorical purposes too: elves have been much grander elsewhere than in Rowling’s work (think of the superiority and otherness of the elves in Tolkien’s work, for example). Rowling’s house-elves are a clear reminder of slavery and servitude. Similarly, centaurs and giants suffer under Umbridge’s domination of Hogwarts, since they are regarded as less than human. Species-ism stands in for racism very easily.

It is worth noting that although dragons and basilisks put Harry and his friends in physical peril, the scariest creatures in the Potter universe are the dementors – creatures Rowling invented herself. These may bear some physical similarity to wraiths, and the Black Riders in The Lord of the Rings, but the psychological and emotional damage they cause is their own. Rowling has linked them with her own experience of depression, reminding us (if such reminders were necessary) that the darkest monsters most of us will face are those in our own minds.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.