The most famous letter never sent?

Morley von Sternberg

Morley von SternbergMarking the birthday of Oscar Wilde on 16 October, Arwa Haider looks at the revolutionary love letter he wrote in prison.

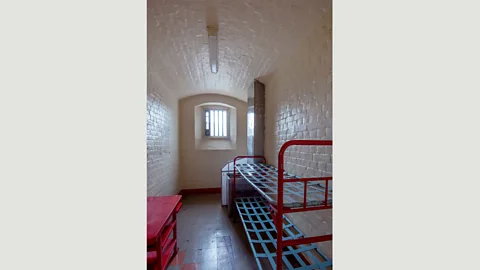

Stepping into the disused Reading prison is an instantly unsettling experience. The air changes inside, and feels leaden; narrow corridors of numbered cells extend in four directions. It was here, in a stifling cell in C block, that Irish playwright, poet, essayist and iconic wit Oscar Wilde spent two years in isolation from 1895, during his imprisonment for “gross indecency”.

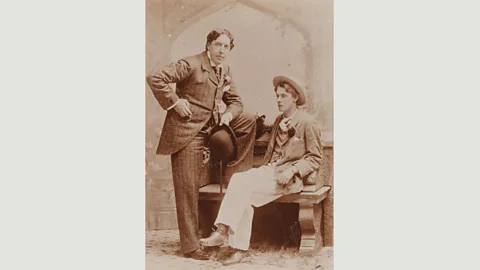

It was a nightmarish contrast to the high-society success he had sealed through literary and theatrical masterworks such as The Picture Of Dorian Gray (1890) and The Importance Of Being Earnest (1895). And it was here, in the months before his 1897 release, that Wilde penned what would widely come to be regarded as one of the great letters of the English language, addressed to his lover and betrayer Lord Alfred ‘Bosie’ Douglas: De Profundis.

On 16 October, 2016 – 162 years to the date of Wilde’s birth – the Irish novelist Colm Tóibín returns to Wilde’s original cell to read De Profundis aloud. The recital forms part of an ongoing major exhibition inspired by Wilde’s letter. Inside: Artists And Writers In Reading Prison is presented by British organisation Artangel and features site-specific artworks from an international cast including Ai Weiwei (who writes one of several intensely personal “letters of separation” left in the cells), Nan Goldin, Marlene Dumas, Tahmima Anam and Juergen Teller.

Morley von Sternberg

Morley von SternbergThe show marks the first time that the building has been open to the public. While the prison’s use has changed over the years (it was a young offenders’ institute before its official closure in 2013), its ominous atmosphere has not waned. Nor has the power of Wilde’s words. In De Profundis, he describes “the plank bed, the loathsome food, the hard ropes shredded into oakum till one’s fingertips grow dull with pain… the silence, the solitude, the shame – each and all of these things I have to transform into a spiritual experience.”

Reading between the lines

Tóibín tells BBC Culture about his first impression of Wilde’s cell. “I think the building makes clear the extent of the misery. It was organised oppression,” he says. Tóibín’s own fiction and academic writing has regularly reflected on Wilde’s life and work, though he mentions that his first reading of De Profundis came well after his youthful fascination with the famous plays and essays and even Wilde’s sorrowful final opus, The Ballad Of Reading Gaol (1898).

“It was much later that I came across De Profundis, and came to understand the circumstances under which it was written, and to appreciate it for its style and tone,” Tóibín says. “Because of its strange publishing history and its hybrid form, I think it was not as well-known as the rest of Wilde’s work.

“I admire it for its style, for its use of repetitions, for the way the sentences are formed. It seems to me to be Wilde’s best work in prose. And because it was written from the depths and deals with forbidden love, then that adds to its interest.”

The circumstances of the letter’s creation are certainly extraordinary. Wilde was languishing under the harsh conditions and extreme isolation of his sentence (prisoners were not permitted contact with each other, even during chapel services). The new prison governor Major Nelson took a more compassionate approach, allowing Wilde pen and paper daily to write a letter “for medicinal purposes”.

In a story for The Guardian, Tóibín described how prisoners were forbidden to write plays, novels or essays – but could write letters. “Under the previous regime, Wilde had written to solicitors and the Home Office, or in limited quantities to friends, but his letters were inspected and the writing materials removed as he finished,” says Tóibín. “But the regulations did not specify how long a letter should be. And if a letter were not finished, then the prisoner, it was supposed, could be allowed take it with him when he left the prison.”

British Library Archive, Oscar Wilde Collection Items

British Library Archive, Oscar Wilde Collection ItemsWilde wrote feverishly over the first three months of 1897, flowing from passionate hurt and bitter accusations against his decadent lover (“Of course I should have got rid of you”) toward a surprisingly spiritual, transformative tone. Because the letter was technically incomplete, it would be returned to him the next day, and its 20 pages – amassing 55,000 words – were presented to him when he was finally released.

Barred writing

As a free but broken man, Wilde passed the letter to his friend and former lover, the journalist Robert Ross, rather than Bosie, to whom it was written. Bosie would later claim he had destroyed his copy without reading it. Ross oversaw its publication, which originally came in 1905 (five years after Wilde’s death, aged just 46), and named it De Profundis (translated as “from the depths”) from Psalm 130. That first publication was heavily abridged, excising all mention of Bosie and his family; while the text was gradually expanded over later editions (including an attempt by Wilde’s son, Vyvyan Holland, to present the complete letter in 1949), Ross entrusted the hand-written original to the British Library, and the unexpurgated version of De Profundis was only published in 1962 – nearly two decades after Bosie’s own death.

De Profundis has drawn various descriptions over the decades, from revolutionary love letter to autobiography to sermon. It does not fit easily into any one category, which is arguably part of why it still elicits such an emotive range of readings and responses. Artangel co-director Michael Morris explains how the Inside exhibition was fuelled by the letter’s “remarkable paradox of expression”, and notes how his own reaction to De Profundis has shifted with life experience. “When I first read the letter two decades ago, I remember being amused by the first section, in which Wilde petulantly accuses Bosie,” says Morris. “I’m now much more compelled by the latter part, where he interrogates the question of sorrow, and its beauty.”

National Portrait Gallery, London

National Portrait Gallery, LondonThe weekly live recitals of De Profundis at Reading prison have ranged widely in length and tone, with readers including Ralph Fiennes and Kathryn Hunter. For contemporary artists such as Nan Goldin, Wilde’s prison experience also irrevocably altered what he represented. “In a way, the Oscar Wilde I was so influenced by isn’t here,” she told The Guardian. “The openly gay, witty Oscar Wilde is not here – just as that part of him wasn’t evident in his writing from the prison. It’s like he disappeared into himself just to survive it.”

Many lines in De Profundis feel strangely modern; its assertion that “sentimentality is merely the bank holiday of cynicism” still strikes a sharp chord. But Tóibín argues that Wilde’s most shocking revelation remains “the supreme vice is shallowness”. “He was the high priest of flippancy and searching for seriousness through its opposites,” says Tóibín. “The tone here is fascinating as he searches for a tone that is filled with seriousness and yet manages not to be solemn.

“He understood his own importance. He gave his name to an era, to a type of sensibility. But in the last years of his life, after he had been released, he suffered a great deal – too much, probably, to consider his legacy.”

That legacy feels more multi-layered than ever; the letter that Wilde never sent continues to deliver unexpected details.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.