Space oddities: David Bowie’s hidden influences

Jimmy King

Jimmy KingAs the legendary musician releases his twenty-eighth studio album, Greg Kot takes a look at the unexpected artists that he has borrowed from and championed.

This story was originally published on 8 January 2016 but amended on 11 January after the death of David Bowie.

Personas, he’s had a few. David Bowie was the Man Who Sold the World, and the Man Who Fell to Earth. He was the Thin White Duke, Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane. And during his Scary Monsters incarnation, he was a white-faced Pierrot. These were attention-grabbing guises, but there was always a musical depth and range of influences behind them.

On Bowie’s new album Blackstar, he worked with a jazz quartet led by saxophonist Donny McCaslin that has been burning up clubs for the last few years in the singer’s adopted hometown of New York. McCaslin’s band gives the album a dark, open-ended atmosphere that loosens Bowie’s ties to rock until sometimes they vanish completely. It was an audacious move for the artist as he turned 69, but hardly uncharacteristic. He had a long history of championing and borrowing from relatively unknown artists and building bridges between distant genres.

Rex

RexWho were these unexpected or underrated influences, and how did Bowie acknowledge them in his music? The list has to begin with the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, a Texas psychobilly pioneer whose ’60s single Paralyzed has come up in many Bowie interviews. The singer accurately described the track as “the most awful cacophony,” but he admired the utter commitment behind the performance. He later adopted part of this rock oddity’s name for his own creation, Ziggy Stardust.

Absolute beginners?

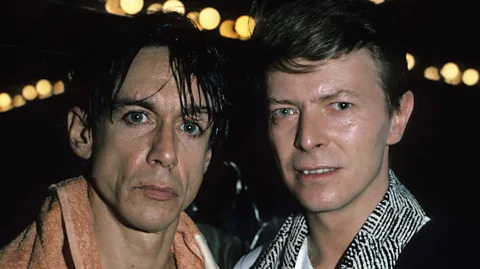

Throughout the ’70s, Bowie used his fame to spotlight his obsessions. His love of the then-obscure Velvet Underground was underlined by his cover of I’m Waiting for the Man and his production of Lou Reed’s solo breakthrough, Transformer. He then hooked up with the leader of another beloved but star-crossed band, the Stooges’ Iggy Pop, to produce two landmark albums, The Idiot and Lust for Life, and even played keyboards for the punk progenitor on tour.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBowie also was enamoured with another young songwriter from that era, a New Jersey kid named Bruce Springsteen. Springsteen’s debut album, Greetings from Asbury Park, was a commercial flop, but Bowie loved its imaginative street tales. He covered two of its songs, Growin’ Up and It’s Hard to be a Saint in the City, and even invited Springsteen to the recording session for the latter, although the tracks didn’t surface until years later.

Bowie’s ‘plastic soul’ phase saw him embracing a young singer and songwriter, Luther Vandross, with whom he co-wrote Young Americans. Vandross became a key part of Bowie’s vocal arrangements, and benefited from the star’s career advice. Vandross once told me that on tour, “Bowie told me to go out there and sing five original songs every night with the band before he went on, and for 45 minutes each night I'd hear, ‘Bowie!’”.

Rex

Rex“I said to him, ‘Listen, man, if you want to kill me, just use cyanide, but don't send me out there again.’ And Bowie just said, ‘Hey, I'm giving you a chance to get in touch with who you are. Their reaction isn't the point. What you do is the point.’”

A few years later, Vandross would become a star in his own right.

The Bowie connection

In the late ’70s, Bowie dashed off his famed trilogy of Berlin albums, Low, Heroes and Lodger, that once again found him dancing on the cutting edge of several seemingly unrelated styles in tandem with his new friend, Brian Eno, formerly of Roxy Music. With producer Tony Visconti, they incorporated the pulse of Euro-disco landmarks like the Donna Summer/Giorgio Moroder hit I Feel Love, the warm electronic German art-rock of Kraftwerk and Harmonia, and the aggression of punk.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1979, Bowie invited avant-garde singers and performance artists Klaus Nomi and Joey Arias to join him for a performance on Saturday Night Live, where the props included a fake pink poodle with a TV screen in its mouth. Thanks in part to the Bowie connection, Nomi went on to establish a brief career as a recording artist before his death in 1983.

In subsequent decades, Bowie made records with luminaries such as Chic’s Nile Rodgers, Mick Jagger, Queen and even Bing Crosby. But amid the mainstream commercial efforts, he continued to explore. He was working with Moby before the electronic artist became a mainstream success, and he brought Turkish multi-instrumentalist Erdal Kizilcay, jazz trumpeter Lester Bowie, drum ‘n’ bass innovator Goldie and guitarists Adrian Belew and Reeves Gabrels into his world.

Rex

RexBowie could’ve easily kept chugging along recycling his biggest ’70s hits on lucrative stadium tours, but for the most part he let musical curiosity lead his career. It’s why the adventures on Blackstar shouldn’t be perceived as a surprise. As Bowie said in the early ’90s when he played his first and last ‘greatest hits’ tour, “I feel confident imposing change on myself. It’s a lot more fun progressing than looking back. That’s why I need to throw curve balls.”

Greg Kot is the music critic at the Chicago Tribune. His work can be found here.