Caillebotte: The painter who captured Paris in flux

Gustave Caillebotte

Gustave CaillebotteThe painter Gustave Caillebotte captured a moment of radical transformation, as the Paris we know today took shape. Jason Farago takes a look.

Here are two things you can dependably say about life in Paris: the sky is usually grey and the fashion is always for black. It’s true today and it was true in 1877, when Gustave Caillebotte depicted the Parisian bourgeoisie sweeping down the streets under a steady, stubborn shower. Just look at them: the couple in the foreground, she with her fur-flecked coat and pearl earrings, he with his moustache framing a permanent moue. The gent to the right of them, tilting his umbrella as he passes; he doesn’t look at the couple, they don’t look at him. A man in the middle ground crosses the street, gazing downward; in the distance, someone without an umbrella darts from one corner to the other.

Gustave Caillebotte

Gustave CaillebotteAnd behind them, fronting the infinite boulevards, are the French capital’s unmistakable cut-stone apartment buildings: commerce on the ground floor, balcony on the second, little chambres de bonnes up top. We’re in the Place de Dublin, as it’s now called, in the eighth arrondissement, hard by the Gare Saint-Lazare. Now the neighbourhood is a bit tatty, but when Caillebotte was painting, it was a brand-new residential district. The slicked cobblestones have now given way to asphalt; the carriage on the left has been succeeded by the car and the bikes of the Vélib’ cycle scheme. But this is still the Paris we know – the modern city, so lonely, so beautiful.

For 50 years, Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day has been in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, but it has traveled to Washington DC for a major exhibition of a slightly overshadowed innovator of 19th-Century French painting. Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, which opens on 28 June at the National Gallery of Art, brings together 50 paintings, and although the show will feature hisself-portraits and lesser-known still lifes, his most enduring images are of Paris in transition. (The show continues to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth in November.)

Caillebotte, not exactly an Impressionist, nevertheless shared his contemporaries’ obsession with painting modern life. That obsession was made manifest not through any great experiment in pictorial style, but via a cool and insistent gaze on the streets, the bridges, and the anonymous passersby in the capital of the 19th Century. He may not have been as daring or as influential as his friends Manet and Monet, Pissarro and Cézanne. But the scenes he depicted – of a Paris in radical transition, as the City of Light morphed from a roiling warren of disorganized streets into a orderly, pacified network of grand boulevards – offer an unrivaled view of a city tumbling into modernity.

Fortune’s favours

Gustave Caillebotte had a short career: born in 1848, he didn’t start painting until his late twenties, and he was dead by the age of 45. Art played no special part in his youth, and his belated training was safe and academic. But Caillebotte had the good luck to come to artistic maturity when the Paris art world was in flower, and the city had put behind it the chaos of the Franco-Prussian War (in which Caillebotte served in the Paris defence force) and the violent suppression of the Commune. He also had an advantage uncommon to most of Paris’s garret-dwelling painters: in 1874, upon the death of his father – who’d had a few good turns on the Paris real estate market – Gustave inherited a whacking fortune.

The cash meant that Caillebotte could work at his own pace, selling almost nothing; the large majority of his art still belongs to his heirs. (He became a major collector; a fair chunk of the Musée d’Orsay’s Impressionist collection used to be his.) It also meant that he didn’t much care when his first great painting, The Floor Scrapers, was rejected for the Paris Salon. In this epochal picture from 1875, three shirtless workers on their hands and knees drag planes along the wooden floor of a bourgeois apartment. The workmen have a bottle of wine to refresh themselves, while outside you can just make out the roofs of the eighth arrondissement. The bold perspective, high above the subjects, isn’t the only unusual thing. Before Caillebotte and his contemporaries, workers were usually depicted – if they were depicted at all – in the countryside. Think, for example, of Gustave Courbet’s The Stone Breakers, painted in 1849-50 (and destroyed during the bombing of Dresden): a blunt and accusatory image of labour and inequality, but ultimately at a remove from the center of power.

Gustave Caillebotte

Gustave CaillebotteCaillebotte’s floor scrapers, by contrast, are right in the capital. The working class is in the city – in the very buildings where the bourgeoisie made its home. Émile Zola, for his part, was impressed but skeptical. “It is anti-artistic painting,” he wrote in June 1876; “painting as neat as glass, bourgeois painting.” He wasn’t totally unfair.

Caillebotte couldn’t help being loaded – the floor-scrapers, several art historians have suggested, were renovating his own studio. But from his perch at the top of the economic hierarchy, Caillebotte had a view of an urban upheaval that was already underway, and would not only change Paris but set the tone for much of Western modernism.

Capital plan

Caillebotte was hardly the only French painter of the 1870s and 1880s to turn his gaze to Paris instead of the countryside. Édouard Manet turned his keen eye to the barmaids of the café-concerts, while Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted revelers in Montmartre as they danced under the Moulin de la Galette. (Who was that painting’s first owner? Big-money Gustave Caillebotte himself: in a self-portrait, you can see Renoir’s large-scale party scene in the background.) What distinguishes Caillebotte from his contemporaries was the focus of his gaze, away from the cancan dancers and onto the street – a place that, no less than Pigalle’s dubious nightclubs, was in the midst of modernisation. As they strut down a rainy boulevard, Caillebotte’s bourgeois passersby are not just looking into space. They are finding their way through a Paris under construction, hurtling into a new era and keen to forget, or suppress, its violent recent past.

Gustave Caillebotte

Gustave CaillebotteThose boulevards, don’t forget, were still pretty new in 1877. In the mid-19th Century, Napoléon III had ordered a massive redevelopment of the unruly French capital – led by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the prefect of the Seine, who boldly (you might say pitilessly) cleared out Paris’s dense, politically restless faubourgs. In their place arose standardised blocks of housing, fronting new extended axes that showcased landmarks like so many imperial baubles. The extended Rue de Rivoli provided a straight shot from the Bastille, where the revolution got underway, to the Place de la Concorde, where Louis XVI lost his head. The Avenue de l’Opéra connected the Louvre to Napoléon III’s hideous new opera house, intentionally stranded on a six-sided traffic island.

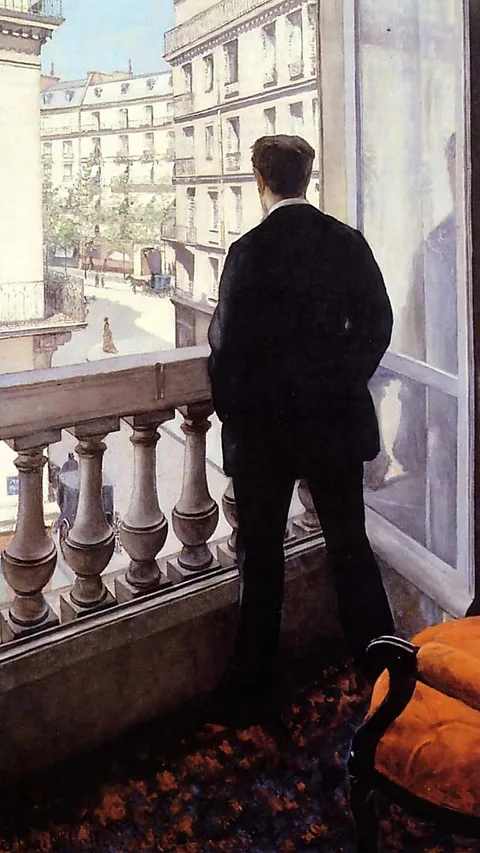

By the time Caillebotte started painting, the Second Empire was over. But the Franco-Prussian War had left numerous neighborhoods in ruins, necessitating further radical neighbourhood reconstruction. Caillebotte looked at Haussmann’s new Paris with a detached, almost forensic gaze. Young Man at the Window, from 1876, shows his brother René from behind, gazing from a new building onto the Rue de Lisbonne, which a woman in petticoats is crossing. Multiple paintings of the Pont de l’Europe, a hulking iron bridge with diagonal struts, turn Paris into a modern but alienated space, in which life hurtles forward but people seem lost.

Gustave Caillebotte

Gustave CaillebotteWhat Caillebotte shows us, as he translated traditions of landscape and genre painting to the boulevards of Haussmann’s new city, is that progress always unsettles. Even on the rigorously laid out boulevards of Paris’s northwest, sometimes you might have no idea where you are. That, more than any formal innovation, might be his greatest legacy – and his greatest appeal for contemporary viewers. It’s worth remembering as we trudge through the streets today, our necks bowed and our eyes on our smartphones, that feeling isolated and disconnected in the midst of millions is not a new phenomenon. It has pervaded the lives of city-dwellers since the earliest days of modernity – a steady and unavoidable human emotion, as constant as the Paris drizzle.