Hogarth’s London: Gin Lane and Beer Street

Städel Museum – ARTHOTHEK

Städel Museum – ARTHOTHEKWilliam Hogarth loved to depict London’s bawdy, boozy side. As a new exhibition of his prints opens at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, Alastair Sooke examines the artist’s view of vice and virtue.

“I know no one who had a less pastoral imagination than Hogarth,” wrote the 19th Century essayist William Hazlitt. “He delights in the thick of St Giles’s or St James’s [in London]. His pictures breathe a certain close, greasy, tavern air.” For my money, there are few pithier descriptions of the work of the English painter and engraver William Hogarth (1697-1764).

Hogarth was rarely compelled to depict bubbling brooks or docile cows. Rather, his subject was the unruly theatre of life offered by society in London, from the slum of St Giles to fashionable St James’s. The 18th Century metropolis was a competitive arena – and Hogarth’s sense of its knockabout nature animated the series of satirical prints, including A Harlot’s Progress and A Rake’s Progress, which made his name.

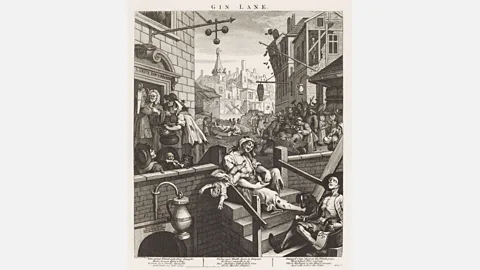

Indeed, his vigorous, swarming, low-life scenes, set in brothels and other nefarious nooks of the city, proved so popular that they inspired an adjective – ‘Hogarthian’ – to evoke the shady milieu that they depict. And the quintessential example of Hogarth’s squalid subject matter is his infamous print of 1751, Gin Lane.

Gin Lane/William Hogarth/Städel Museum – ARTHOTHEK

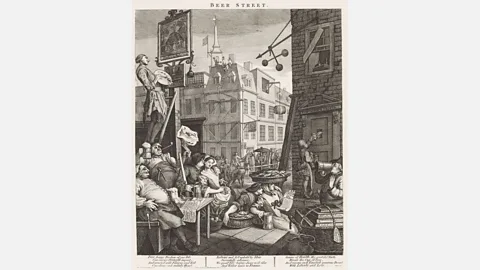

Gin Lane/William Hogarth/Städel Museum – ARTHOTHEKAccording to Hogarth, this urban hellscape was “calculated to reform some reigning Vices peculiar to the lower Class of People”. Along with its pendant, Beer Street, it is among 70 works on show in a new exhibition, Vices of Life: The Prints of William Hogarth, at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt.

By the time he executed Gin Lane, Hogarth had already reached the height of his career. Born the son of a bankrupt schoolmaster, he endured an impoverished childhood, before becoming apprenticed to a silver engraver. In his early twenties he set up on his own, churning out trade cards and lowly book illustrations. At this stage, he was still a hack.

Yet thanks to his talent, as well as his business acumen (something he did not inherit from his father, who ran a coffee shop that failed, and spent four years as a debtor in the notorious Fleet Prison), Hogarth achieved success as a professional artist.

In the 1730s, he pioneered a new form of art that he termed his “modern moral subjects”: series of pictures narrating stories about conduct and character. The first one, A Harlot’s Progress, was a hit: at least 1,240 sets were printed for subscribers at a price of one guinea each.

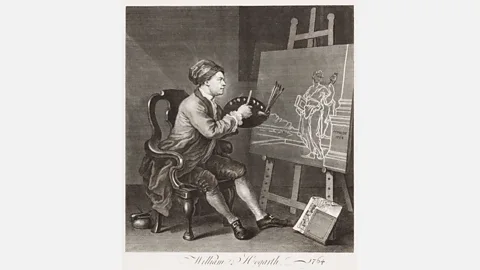

Städel Museum – ARTHOTHEK

Städel Museum – ARTHOTHEKDuring the decades that followed, Hogarth played an increasingly prominent role as both a portraitist and a printmaker in London’s art world, culminating in his appointment, in 1757, as Sergeant-Painter to the King. Two years before the publication of Beer Street and Gin Lane, he was already wealthy enough to afford a country house in Chiswick.

Spirit of the times

The context for Beer Street and Gin Lane was the so-called ‘Gin Craze’ of the first half of the 18th Century. “In 1689, an Act of Parliament banned the import of French wine and spirits,” explains Annett Gerlach of the Städel Museum. “At the same time, the British government encouraged the distillation of spirits from indigenous crops by diminishing taxes and other contributions paid by landowners.”

The result, in an era of conflict between Britain and France, was an affordable, native alternative to French brandy. “And since gin was cheap,” Gerlach continues, “it was consumed especially among the poorer strata of society. Its enormous ‘success’ at the time is proved by the fact that one out of five households sold gin in the slum of St Giles-in-the-Fields alone – whereas the ratio was one out of 15 in Westminster.” According to one estimate, by 1743, England was drinking 2.2 gallons (10 litres) of gin per person per year.

Among London’s chattering classes, gin quickly became a bête noire. Concerned citizens such as the novelist Henry Fielding, who was a friend of Hogarth, held the spirit accountable for the sharp increase in disorder, criminality and infant mortality blighting London. The Gin Craze has even been compared to the abuse of crack cocaine in inner cities today.

Fielding was one of a number of prominent campaigners whose efforts resulted in the Gin Act of 1751, which helped to curb the epidemic. Hogarth created Beer Street and Gin Lane in order to add some punchy visual rhetoric to the same campaign. Rather than commission master-engravers from France, as he occasionally did when pitching new prints to upscale connoisseurs, Hogarth produced the plates himself to ensure they remained affordable for a large audience.

Mothers’ ruin

The pictures provide alternative visions of London. Gin Lane thrusts us into the abyss of the slum of St Giles north of Covent Garden, where alcoholic mothers pour gin into the mouths of their offspring. The central figure, a crazed, half-naked prostitute with syphilitic sores on her legs, is oblivious of her baby tumbling to its death.

Elsewhere, destitute gin drinkers are reduced to a brutal, feral existence. A carpenter and a housewife wearing ragged clothes desperately pawn their tools and pots and pans in order to fund their habit. Behind the parapet a boy competes with a dog to gnaw on a bone. The cadaverous ballad-singer slumped in the foreground is in a woeful state of ill health. His black dog symbolises despair.

Meanwhile, in the background, actual corpses are visible – including the hanged barber in the upper storey of a partially ruined house. In this section we are confronted by a frenzied crowd of drunkards, cavorting and causing havoc: one lunatic clutching a pair of bellows to his head even dances a jig while waving a spike upon which a baby has been impaled – a figment from a nightmare. This is a gin-fuelled, topsy-turvy world of mob rule, precipitating the breakdown of society in general – symbolised by the collapsing building at the far end of the miserable vista.

William Hogarth/Städel Museum – ARTHOTHEK

William Hogarth/Städel Museum – ARTHOTHEKBeer Street, by contrast, is the heaven to Gin Lane’s hell. Set in Westminster, where trades and crafts are seen to thrive, rather than St Giles where the poverty-stricken residents are feckless and unemployed, it features healthy, well-fed labourers at leisure, enjoying large, frothing tankards of the national brew. A newspaper on the table reports a speech by the king recommending “the Advancement of Our Commerce and cultivating the Arts of Peace”. Nearby, fishwives with overflowing baskets suggest that a society based on solid, honest mercantile values – untainted by that foreign spirit, gin – will be rewarded with abundance and prosperity.

Hazlitt was right: Hogarth did not have a pastoral imagination. But the happy celebration of Englishness in Beer Street, as its rustic sign of The Barley Mow inn reminds us, is as close to ‘pastoral’ as the artist ever came. And while Beer Street and Gin Lane may have been rooted in a specific issue of Hogarth’s own time, “the realism and keen social interest he stands for,” says Gerlach, “as well as his impressive powers of perception and caustic humour, still attract and engage audiences today.”

Alastair Sooke is art critic of The Daily Telegraph