Behind rock’s finest album cover: A timeless friendship

Robert Mapplethorpe’s photo of Patti Smith on the sleeve of Horses is considered one of music’s best. But the story of their friendship between the two is more beautiful, writes Stephen Dowling.

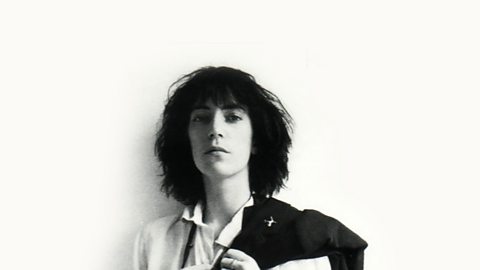

It is considered one of the greatest album covers of all time. A simple portrait to the waist of a woman in a crisp white shirt, a black ribbon draped over her shoulders, dark jeans. Her jaw is jutting out proudly, defiantly. A jacket is slung over her shoulder. The wall she is leaning against is as brilliant a white as her shirt, a blank and blinding canvas.

It is the cover of Patti Smith’s debut album Horses, taken in a Greenwich Village apartment sometime in 1975 by Smith’s longtime friend, Robert Mapplethorpe. Mapplethorpe and Smith were both in their late 20s and veterans of a bohemian New York art scene that had created the fledgling ranks of the city’s punk rock scene. Smith’s album would make her one of the biggest stars of the New York punk scene, alongside the Ramones, Blondie and Talking Heads, and mark her as an influence on everyone from REM to PJ Harvey to Garbage’s Shirley Manson.

The photo shoot that became the cover for Horses is a defining moment. "The only rule we had was, Robert told me if I wore a white shirt, not to wear a dirty one," Smith told NPR in 2010. “I got my favourite ribbon and my favourite jacket, and he took about 12 pictures. By the eighth one he said, 'I got it'." Today, the print is part of the Tate Collection in the UK, and rightly regarded as a classic portrait.

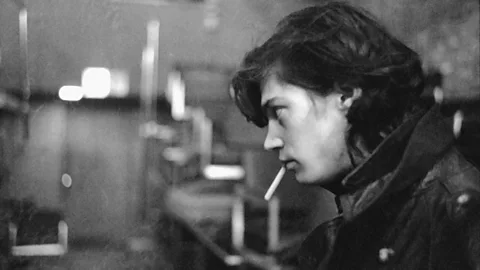

By the time Mapplethorpe took this photograph, he and Smith had known each other for nearly a decade. They met in 1967, on the very first day Smith moved to New York from New Jersey; she later recounted him looking like a "hippie shepherd boy" with dark curls.

Chance encounter

The meeting was in Brentano's bookstore on Fifth Avenue, where Mapplethorpe bought one of her favourite necklaces. “Don’t give it to any girl but me,” she told him. Smith wanted a promise from Mapplethorpe, but that was not the promise that would define their 22-year friendship. That would come at the end.

Getty Images

Getty Images“I was a bad girl trying to be good and he was a good boy trying to be bad,” Smith wrote in Just Kids, the 2010 book that defined their relationship and was published two decades after Mapplethorpe's death. They lived together for a time, often in squalor, in the cheapest room at the Chelsea Hotel, the Ground Zero of alternative, artistic New York. “The Chelsea was like a doll’s house in The Twilight Zone, with a hundred rooms, each a small universe,” wrote Smith. “Everyone had something to offer and nobody seemed to have much money. Even the successful seemed to have just enough to live like extravagant bums.”

They were lovers until Mapplethorpe, one of five children from an Irish Catholic family, realised he was gay. Despite this – despite Mapplethorpe ending their physical intimacy – their relationship endured. It was no longer as lovers, but as artistic partners and friends. “When we were together, he didn’t tell me about his exploits, and I didn’t talk to him about other people. When we were together, we were with each other,” Smith told New York Magazine.

Mapplethorpe and Smith’s relationship endured through the 1970s and ‘80s, though it was less intimate. Smith was often on the road with her band, and she moved to Detroit after marrying the one-time MC5 guitarist Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith. And Mapplethorpe’s photographic vision became more extreme and uncompromising, as he created often graphic male and female nudes. Smith wrote in Just Kids that Mapplethorpe’s photographic preoccupations began to disturb her.

Record of a friendship

Mapplethorpe divided his time between New York and San Francisco, enjoying a feted, celebrity lifestyle. Smith was in Detroit, raising a family, in semi-retirement from her own artistic career.

In 1989, Mapplethorpe lay dying from complications related to Aids. The day before he died, aged 42, Smith made him a promise – she would recount the story of their life together and ensure his photographic legacy would live on.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMapplethorpe’s photographic canon, it’s fair to say, had moved far away from the classic portraiture on the cover of Horses. His first shows in New York in the late 1970s fixated on the sadomasochistic, a mood that would come to dominate his work. Some is pure pornography, designed to cause sexual arousal. “He was equally entranced by raunch and glamour, by the danger of a sexual underworld and the pampered allure of affluence,” wrote Peter Conrad of the Guardian in 2006. Mapplethorpe’s 1978 collection, X Portfolio, created a scandal due to its pornographic nature; when some of the material toured the US shortly after his death, some of the galleries involved were charged – and later cleared – of indecency.

In the years following Mapplethorpe’s death, Smith also had to endure the double tragedies of her husband’s death from a heart attack in 1994, and also that of her brother, a longtime member of her touring party, months later. And she had to raise two young children. But she did not forget her part in keeping Mapplethorpe’s vision alive. When the photographer’s work was exhibited in Paris next to statues by Michelangelo, it was at Smith’s behest. Only she knew how much the Renaissance artist had influenced Mapplethorpe’s early work, when he was drawing before taking up photography.

Alamy

AlamyMapplethorpe’s reputation has only grown, partly thanks to Smith becoming his champion and partly because of the work of his own foundation, set up to keep his work alive and to fund the causes he supported. Exhibitions continue to be staged around the world, and prints command high prices; one Mapplethorpe portrait of Andy Warhol, taken in 1987, sold for $643,200 in 2006.

Just Kids is Smith’s most personal part of her pledge, and possibly the most difficult; it would take her nearly 20 years to complete, with Smith struggling through draft after draft. "I probably wouldn't have been able to finish it, except I promised him I would and I knew in my journey after death, if I bumped into him, which I know I would, he'd be so mad at me,” Smith told the Guardian in 2013. “You know, 'Patti, you didn't write our book. Why didn't you finish the book?' I could feel him scolding me, so I did finish it."

Read more from Unbreakable: Stories about the strength of a promise.