Victoria and Albert: How a royal love changed culture

Alamy

AlamyMuch we take for granted today – from Christmas trees to birthday gifts – comes from the domestic traditions of the royal couple, writes Lucinda Hawksley.

When Queen Victoria inherited the British throne just a few weeks after her 18th birthday, there was immediate speculation about who she would marry. Few had foreseen that this little-known princess would become their monarch. But when the country found itself with a young queen after so many dissolute Hanoverian kings, it seemed that exciting new era was dawning.

Queen Victoria’s mother and the government had expected her to marry her cousin Prince Ernst, eldest son of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. So when Victoria fell in love with Ernst’s younger brother, Albert, the public was enthralled. The media made much of the fact that the queen’s fiancé was of her own choosing and that she, being of a higher rank, had proposed. The British were so used to royal marriages being business contracts that a genuinely romantic royal love match was keenly observed.

This overwhelming love shared by a queen and her prince would change British culture forever. Many of the traditions we take for granted today, and the artistic legacies we celebrate, emerged from Victoria and Albert’s marriage.

Both the queen and her consort were accomplished artists, as well as great collectors. In addition to paintings and sculpture, the couple also commissioned love tokens from jewellers and helped boost that industry. When Prince Albert gave Queen Victoria an engagement ring – an item little known in Britain in the first half of the 19th Century – he began a new fashion that has endured ever since.

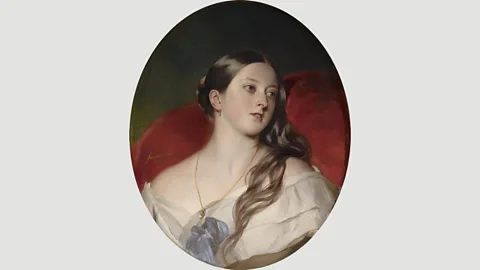

Gift-giving as we know it now took its form under Victoria and Albert too. They gave – and expected – gifts at every wedding anniversary, birthday and Christmas celebration, usually of works of art. (And of course we all know how Albert helped introduce the German tradition of the Christmas tree into British life.) They loved to surprise each other with a ‘secret’ present, such as the surprisingly sexy painting of the young Victoria, with tendrils of hair tumbling over bare shoulders, by German artist, Franz Winterhalter (1805-73). The painting was commissioned by the queen as a present for her husband’s 24th birthday, in 1843. Over a decade after his death, the queen wrote fondly about the painting in her journal as “my darling Albert’s favourite picture”.

Corbis

CorbisAlthough Victoria often favoured artists from her mother’s and her husband’s native Germany, most notably Winterhalter, they also commissioned British artists. At Christmas 1841, the queen gave Prince Albert a painting by Edwin Landseer of the prince’s favourite greyhound, Eos, and Landseer was regularly engaged to paint royal pets from then on. The queen also loved the works of the Pre-Raphaelite rebel turned society-portrait painter John Everett Millais (1829-1896), whose portrait of her adored Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was ordered to be garlanded with black mourning when Disraeli died. In the 1850s, the young Frederic, Lord Leighton knew his career was assured when his first major sale was to the queen. Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna, painted when Leighton was living in Rome, was exhibited at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1855. Victoria noted in her journal “Albert was enchanted by it – so much so that he made me buy it”.

New frontiers

Despite presiding over an age when it was considered shocking for a woman to show so much as an ankle in public, the queen was happy for her family to live surrounded by nude statues and paintings of frolicking naked nymphs. The artist William Edward Frost was renowned for painting nudes, and the queen and Prince Albert bought several of his works. At Osborne House, the family’s home on the Isle of Wight, the queen commissioned Scottish artist William Dyce to paint the fresco Neptune Resigning to Britannia the Empire of the Sea, a scene which contains a mass of nude bodies – male and female – about which Dyce recorded that the prince consort was shocked. On his birthday in 1857, Albert was presented with a statue of Lady Godiva, modelled in sensuous silver, gold and enamel. It was by the French sculptor Pierre-Emile Jeannest, whose work Albert had admired at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Alamy

AlamyAlbert’s delicate sensibilities may have been offended by Dyce’s painting, but he was progressive about the arts in many respects and even became a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. The queen was more circumspect. She loved poetry, especially that by her poet laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and said that his mourning poem, In Memoriam was a great comfort after being widowed. She seems to have liked traditional forms of writing, but professed to despise the fashion for novels, especially when practised by women. She sacked her daughters’ French governess when she discovered that the princesses had been encouraged to read a novel in French.

Scottish authors Robert Louis Stevenson and Sir Walter Scott also owe Victoria a debt – in fact, the royal couple’s love of Scotland also changed the very idea of what was ‘British’. Until her reign, Scotland and England’s rivalry remained at a fever pitch, with England seeing itself as superior. But when the queen fell in love with Scotland, visiting her home in Balmoral as often as she could, the rest of the British Isles did likewise. Suddenly tartan was immensely fashionable and couture houses reflected the new fad. The novels of Sir Walter Scott became massively popular to read, even though he had died five years before she began her rule, and Scotland’s tourism industry began to boom.

Family photos

Queen Victoria also embraced the very latest artistic medium: photography. She was the first British monarch to have almost her entire reign recorded in photographs. As early as 1842, she and Albert began to collect photographs and helped photography become even more mainstream after its inclusion at the Great Exhibition of 1851, over which the royal couple presided. Victoria and Albert often sat for photographers and this new fashion saw a burgeoning photographic industry set up across Britain.

Alamy

AlamyIn this era before social welfare payments, the responsibility of those with money to take care of those without, was a necessary part of the British class system. Similarly, wealthy art lovers understood the need to support artists, writers and craftspeople through regular patronage. Being a discerning patron was considered an essential part of a wealthy young man’s education. It was a system that relied upon the aristocracy being well educated in the arts and wanting to show off their knowledge by taking on protégées. To that end, it became usual for Victoria and Albert to pay artists, such as the father-and-daughter sculptors John Francis and Mary Thornycroft an annual salary – rather than per commission. John Francis was hired as Prince Albert’s sculpting tutor and he recommended his daughter when the royal couple were seeking a sculptor to create statues of their children. Mary Thornycroft remained a part of the royal household for many years, becoming the teacher of Victoria and Albert’s daughter, Princess Louise (who became a professional sculptor).

The queen also supported the performing arts, regularly attending the theatre and concerts. Victoria was the first British monarch to ennoble members of the acting profession, endowing the actor Henry Irving with a knighthood and making actress Ellen Terry a dame.

Artistic collectors such as the queen and prince consort were an absolutely vital part of Britain’s artistic heritage and their love of the arts helped to transform the country. In a world hidebound by the rigidity of the class system, an entirely new stratum of society – a creative class – was created throughout Queen Victoria’s reign. By the last quarter of the 19th Century, successful artists, writers, artisans and actors had become considered a new elite.

Read more from Unbreakable: Stories that remind us of the strength of a promise.