The ‘90s: The decade that never ended

It’s amazing how little art has changed since the decade of grunge rock and Ally McBeal. We’re stuck in a rut and can’t move on writes Jason Farago.

How long does it take for the present to become history? Once our museums and universities were guardians of the past, but now they seem ever more concerned with the here and now. But what was once new must inevitably turn old, and historically minded curators are beginning to turn their gaze to the 1990s: a decade that feels like only yesterday and yet like ancient history all at the same time.

They’ve been coming thick and fast, these ‘what were the ‘90s?’ surveys. In 2013, the New Museum in New York presented NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, which filled the museum’s entire building with art from the year of Bill Clinton’s inauguration. Last year, the Centre Pompidou’s satellite space in Metz unveiled 1984–1999: The Decade, which showcased the generation that put French art back on the global art world’s map. And opening this week at New Jersey’s Montclair Art Museum is Come As You Are: Art of the 1990s, a hotly anticipated full-scale survey of the last decade of the last millennium.

The passing of the 1990s into history may feel a little sudden but this wave of 1990s shows marks a welcome effort to impose historical rigour on a period we still sometimes call ‘contemporary’. By insisting on the distance between then and now, and by placing the works in the context of their times – Clinton and Blair, Bosnia and Rwanda, grunge rock and Ally McBeal – these shows do the great service of showing how this art came to be. Yet these exhibitions do something else too: they reveal that the gap between then and now might not be as gaping as presupposed, and that, in aesthetic terms at least, the ‘90s are still going strong 15 years past their expiration date.

Dream of the ‘90s

If you want to understand the art of the 1990s, you have to start not with aesthetics but with economics. The 1980s, especially in New York but also in cities from Cologne to Tokyo, was a period of media excess and frenzied stock market speculation, typified by aggressive large-scale painting that sold for lots of money. But in 1991 the art market crashed spectacularly, closing galleries right and left. Prices fell by more than 50% for many contemporary artists, and average art prices didn’t recover their pre-crash height until 2003. (Now they are even higher, of course.) Art in the 1990s, in economic terms but also in aesthetic ones, went through a period of retrenchment and rethinking. “Value in everything is being questioned,” said Mary Boone, the influential 80s art dealer, in the midst of the crash. “The psychology in the 80's was excess; in the 90's, it's about conservation.”

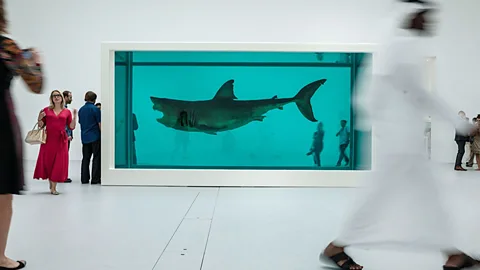

What typified the art of those days? Race, sexuality and multiculturalism were hotly debated at the start of the decade, notably at the controversial Whitney Biennial of 1993, of which the most famous artwork was an admissions button, designed by Daniel J Martinez, reading “I Can’t Imagine Ever Wanting to Be White.” The rise of the World Wide Web had a strong influence on art production. So did celebrity culture, especially in Britain, where the Young British Artists hit the galleries and the tabloid front pages. The big theme was globalisation. That was reflected not only in the art of the time, but in the institutions that arose from it: the 1990s was the decade when biennials, from Johannesburg to Montreal to the South Korean city of Gwangju, became central nodes in artistic production and transmission.

Both the New Museum’s show and the current Montclair exhibition look only at art produced in the United States. That’s a shame, since the 1990s was the decade when national boundaries came crashing down as a meaningful way to delineate artistic style. The decade’s most important art book was Relational Aesthetics (1998), by the French curator Nicolas Bourriaud, who argued that art had become no longer a collection of objects but “a state of encounter… The work of every artist is a bundle of relations with the world, giving rise to other relations, and so on and so forth, ad infinitum.” Those words describe well the art of many French artists who came to the fore that decade, but they apply just as well to Douglas Gordon of the UK, Rirkrit Tiravanija of Thailand and many others.

Only a small number of the iconic artists who came of age in the 1990s worked in traditional media: Elizabeth Peyton, say, who won renown for her delicate drawings of Kurt Cobain and Leonardo DiCaprio. Most of the artists we now think of as representing the ‘90s abandoned a commitment to any one medium, and began creating objects, events or experiences that visitors interacted with directly. So Félix González-Torres assembled mountains of sucking candies, which gallery-goers consumed one by one. Rirkrit Tiravanija served a curry to gallery visitors, gratis. Piotr Ulkański turned the floor of a gallery into a light-up dance floor. In 1997, Jeremy Deller collaborated with a brass band in Manchester, who played acid house arranged for tubas and trombones. The artist’s reaction was a classically ‘90s one: “I realised that I didn't have to make objects anymore. I could just do these sort of events, make things happen, work with people and enjoy it.”

Re-rewind

Some of the art of the 1990s looks decidedly dated. Net art went the way of “You’ve got mail.” Slick, digitally altered large-format photography has gone out of fashion, too; Sam Taylor-Wood (now Taylor-Johnson) gave up art completely and is now directing the softcore Hollywood flick Fifty Shades of Grey. But what’s surprising – and a little disturbing – is how much art from the 1990s could have been made last week. It’s not just that the themes of the ‘90s, from the meaning of identity to the impact of economic transformations, are our themes too. It’s also the style and the feel of the ‘90s that endures, so much so that these historical exhibitions of ‘90s art can feel almost comically fresh.

What if the 1990s, far from being ancient history, are actually still going on? The social practices of gallery spaces that arose in that decade remain the lingua franca of contemporary art everywhere, and video installations that were innovative in the ‘90s now form part of every contemporary exhibition. Since then… what’s new? There has been a noted turn to performance in the 21st Century, and a market-happy revival of abstract painting, but other than those small trends the ‘90s settlement endures. People will still queue for a free curry in an art museum; the only difference is that they snap it with their cameraphones before eating.

For the political theorist Francis Fukuyama, history ended in 1989 – the big questions had all been answered, and the ‘90s were the first decade of a final era of democratic capitalism. By the start of the 21st Century, of course, Fukuyama’s thesis was brutally discredited, and endless crisis has brought history roaring back to life. But if we cannot speak of an end of history, can we perhaps speak, in a Fukuyaman sense, of an end of culture? Art will continue to be produced forever; that isn’t in doubt. But the regular succession of periods and movements that typify art history might be done for – and the ‘90s may turn out to be much more than a point on a timeline, but the first decade of a much, much longer era of stasis.