Why museums hide masterpieces away

In major museums around the world, some truly great works of art are hidden away from public view. What are they – and why can’t we see them? Kimberly Bradley finds out.

The numbers don’t lie. At New York’s Museum of Modern Art, 24 of 1,221 works by Pablo Picasso in the institution’s permanent collection can currently be seen by visitors. Just one of California conceptual artist Ed Ruscha’s 145 pieces is on view. Surrealist Joan Miró? Nine out of 156 works.

The walls of the Tate, the Met, the Louvre or MoMA may look perfectly well-hung, but the vast majority of art belonging to the world’s top art institutions (and in many countries, their taxpayers) is at any time hidden from public view in temperature-controlled, darkened, and meticulously organised storage facilities. Overall percentages paint an even more dramatic picture: the Tate shows about 20% of its permanent collection. The Louvre shows 8%, the Guggenheim a lowly 3% and the Berlinische Galerie – a Berlin museum whose mandate is to show, preserve and collect art made in the city – 2% of its holdings. These include approximately 6,000 sculptures and paintings, 80,000 photographs, and 15,000 prints by artists including George Grosz and Hannah Höch.

“We don’t have the space to show more,” says Berlinische Galerie director Thomas Köhler, explaining that the museum has 1,200 sq m in which to display works acquired over decades through purchases and donations. “A museum stores memory, or culture,” explains Köhler. But here, like in other museums around the world, many works rarely if ever see the light of day.

A spatial deficit is only one reason why not. Another is fashion: some holdings no longer fit their institutions’ curatorial missions. Lesser works by well-known artists may also languish – their hits hang on museum walls; their misses lie forgotten in flat files. Works that come to a museum within estate acquisitions “might sit around in crates for years, waiting to be sorted,” explains Köhler. Some works stay under wraps due to delicacy or damage – and different institutions have varied storage and rotation policies, depending on a collection’s nature and scope. While London’s National Gallery uses a double hang system, thereby increasing the number of its permanent works on view, the Albertina in Vienna possesses more than a million Old Master prints – many of them centuries old and very sensitive. The percentage on view is thus very low, even if most of the holdings are kept onsite. (Other museums keep their caches in secret offsite warehouses.)

“Having 5% of your national collection on show is something people find difficult to understand,” says British curator Jasper Sharp, who was the commissioner of the Austrian pavilion at the 2013 Venice Bienniale. Many art institutions are thus coming up with ways to show their stuff, so to speak. “There is a great move to open up collections,” adds Sharp. Besides digitising images of the permanent collection (which many major institutions are currently in the process of doing), one way to display holdings is the idea of the Schaulager (translation: ‘storage display’) – in which visitors can see works archived, on sliding racks, behind glass, or during restoration. The Hermitage’s storage facility opened in 2014 and offers guided tours of collections long unseen; a number of US museums, like the Brooklyn Museum of Art have also created accessible storage centres. Other museum expansions – the Tate, the MoMA, and the Met are just a few currently underway – are meant to increase space for permanent collection viewing.

Until visible storage is everywhere – or museums grow so large that everything is on view, like a massive database – here are a few examples of wonderful things not often seen, and why.

Albrecht Dürer, Young Hare (1502)

Albertina Museum, Vienna

Dürer’s famous watercolour and gouache drawing Young Hare is a masterpiece in observation; its impeccable rendering served as benchmark for centuries thereafter. As 'Vienna’s unofficial mascot', the work on paper is also the Albertina’s prize possession, but it’s not often on show. After a maximum of three months, Young Hare needs five years in dark storage with a humidity level of less than 50% for the paper to adequately rest. It was on view briefly in 2014 after a break of ten years, and will appear again for a short time in 2018, before it goes back into hiding. The museum holds millions of works on paper, and is thus able to show “less than 1% – maybe even 0.1% – of our collection,” according to deputy director Christian Benedik, but, as mandated by the museum’s original owners (part of the Habsburg royal family) every graphic work has a facsimile that can be viewed more readily, including one of Young Hare. A Google Cultural Institute Gigapixel image of the Hare is digitally viewable – the better to see the reflections in the bunny’s eyes with.

Henri Matisse, The Swimming Pool (1952)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

The undulating ultramarine waves and swimmers of Henri Matisse’s The Swimming Pool, a large paper installation made for the artist’s dining room in Nice, are in fact currently on view in the exhibition Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs until February 10 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. But the work, acquired by MoMA in 1975, was out of sight for nearly 20 years. Its burlap backing had become discoloured and brittle; the white paper frieze on which the blue cut-outs were mounted was stained. The long process of the work’s restoration was indeed the impetus behind this highly acclaimed exhibition that represents Matisse’s last major work series; after the exhibition closes, the work will be unpinned and returned to customised, climatised storage cases. But the situation behind its temporary retirement isn’t completely unusual – often, an artwork needing restoration will wait months, even years for an update.

Jackson Pollock, Mural on Red Indian Ground (1950)

Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran

In the last years of the Iranian Shah’s rein, during a particularly flush oil-boom period, the Iranian queen Farah Pahlavi assembled a formidable collection of modern art, now valued at several billion US dollars. The Picassos, Pollocks and Warhols (among many other household names) in Tehran’s Contemporary Art Museum were viewable from the museums’ opening in 1977 until the Iranian Revolution in 1979 at which time the art was deemed ‘Western’, ie decadent and unsuitable for viewing. Curators spirited the art away into a climate-controlled basement vault – there, it has been safe not only from climate extremes but also knife-wielding revolutionaries. The artworks are often lent to other world institutions, but display in Tehran depends on who is leading the country – a few works were mounted in a Pop Art/Op Art show here in 2005, but any works depicting nudity or homoerotic overtones, like Bacon’s Two Figures Lying on a Bed With Attendants, remain hidden.

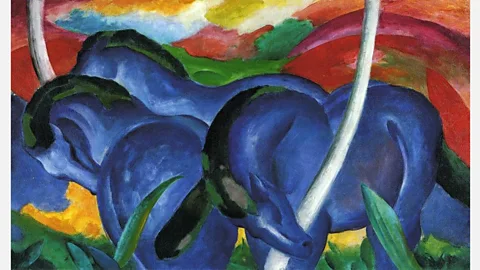

Franz Marc, The Large Blue Horses (1911)

The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

The Walker Art Center’s current incarnation dates from 1940, and its first acquisition was The Large Blue Horses by the German painter Franz Marc. The painting – which Adolf Hitler had deemed ‘degenerate’ and whose sale to the Walker in 1941 was finalised the week bombs fell on Pearl Harbor – represented the museum’s first foray into modern art, at the time a daring move. In the intervening decades, the Walker’s curatorial emphases have shifted: the museum is known for its post-1960s holdings and performance programs, and the painting is seldom shown. “It’s been one of these mythic works in the collection that rarely gets exhibited,” says curator Eric Crosby. “This is a work that is very much central to the Walker’s mission in the 1940s – but as contemporary art has changed we have less context in which to exhibit it.” Nonetheless, the Marc is on view there now until September 2016 in a special anniversary exhibition Art at the Center, 75 Years of Walker Collections.

Edward Kienholz, The Art Show (1963-1977)

Berlinische Galerie, Berlin

At the Berlinische Galerie, American artist Edward Kienholz’s The Art Show – a large-scale installation of visitors viewing an exhibition, with ventilators where their mouths should be – is rarely on view simply because its scope requires an entire gallery within the museum. According to museum director Thomas Köhler, Kienholz’s work, an example of Assemblage art, also takes a great deal of energy and time to assemble properly. Portions of the piece – a figure’s vintage spectacles, for example – also often need to be replaced, sending the restoration team to flea markets.

The Coronation Carpet (1520-30) and Ardabil Carpet (1539-40)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

It's a tale of two carpets, times two. The Ardabil Carpet is well-known to visitors of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The lusciously detailed Persian textile is covered to preserve its centuries-old fibres and lit for only 10 minutes each hour. But there is a slightly smaller version at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), along with second similar rug called the Coronation Carpet, so named because it was laid before the throne at Westminster Abbey for the crowning of Edward VII in 1902. The LACMA rarely displays either, because of their large size and extreme sensitivity to light. It pays to be cautious: a mere scrap is all that’s left of the Coronation Carpet’s mate, on display at Berlin’s Museum of Islamic Art.

Tino Sehgal, This is Propaganda (2002)

Tate Modern, London

British-born, Berlin-based artist Tino Sehgal turns art storage on its head. Why? As performative work – executed not by Sehgal himself but by his trained ‘interpreters’ – it is completely immaterial. Unlike other artists in this field, Sehgal also stipulates that no record whatsoever remains of the work – no photos, no recordings, no press releases; only the experience. That rule even extends to institutional sales agreements of his piece – a sale like that of This is Propaganda, which Tate bought in 2005, is verbally executed. The artist, the buyer, a lawyer and a notary are present; all rules and regulations around the piece are committed to a designated person’s memory. So This is Propaganda (which sees a gallery guard singing “This is propaganda, you know, you know, this is propaganda, Tino Sehgal, This is propaganda, 2002” to every visitor who enters the space) exists only in the mind. Imagine that.