'I don't open restaurants, I tell stories': Chef José Andrés on his singular approach to food

BBC

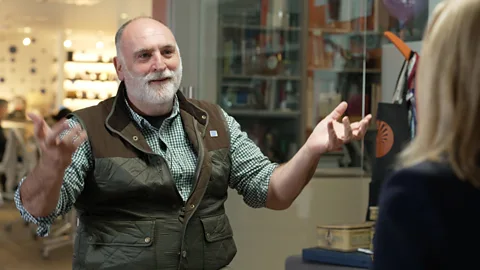

BBCThe restaurateur and Nobel Peace Prize-nominated chef tells the BBC's Katty Kay about his vision for each dish on the plate, and how food should be both an oasis and force for good.

"I don't open restaurants, I tell stories," says José Andrés. "Every one of my restaurants in a way is a story."

The two-Michelin-starred chef has been spinning narratives with food for the past four decades through his portfolio of American restaurants including Jaleo, The Bazaar and minibar. Along with his world-famous dishes, Andrés has also used his platform and talent to build up World Central Kitchen (WCK), a global supply chain of pop-up meal operations that appear in emergency disaster zones to provide direct aid.

Andrés talks with BBC correspondent Katty Kay on Influential, her unscripted interview series, which has hosted conversations with guests including culinary and cultural icon Ina Garten, beauty entrepreneur Jane Wurwand and ground-breaking ballet dancer Misty Copeland.

Where to find Influential with Katty Kay

Andrés found his way into food aged 15, when he enrolled in culinary school in his native Spain; at 18, he entered the Spanish military for compulsory service, becoming a cook for an admiral on a boat. The experience took him outside Europe for the first time, opening his mind to the meaning of collaboration and the possibilities of global impact.

"The military service gave me this sense that we are a part of making our country better, our world better and it also showed me the meaning of working as a team," he tells Kay. "When I was sailing on that ship, I understood that the winds may be against us, and the currents may be moving us in the wrong direction – but the 300 people were together as one, no waves or currents that could take us away from our destination."

Soon after, Andrés met chef Ferran Adrià of El Bulli, the iconic three-time Michelin-starred restaurant in Roses, Spain. He spent the next three years in the kitchen at the height of the restaurant's nearly 50-year run. It helped pave the path for Andrés's own success when he landed in New York, then moved onto Washington DC, amid a booming desire for singular food experiences.

"I've been given a lot of credit for making Washington DC a force, and I did my part when I arrived, but this city was already culinarily extraordinary," he says. "Washington was not seen as a great culinary city compared to other cities, like Chicago and New York, but, actually, it was [already] super powerful."

Still, Andrés will lay claim to at least some of the innovation in the culinary space. What differentiates him from flash-in-the-pan food-scene trends, he says, is his approach: reflecting real-life, emotional experiences on each plate. "When somebody comes to Jaleo and gets a croqueta, they are not eating just a dish that is a very iconic tapa in Spain, they're eating a dish from the post-Civil War era. If you go deeper, that dish itself can be talking about social and political situations in Spain, war and the hunger of low-income families in a much deeper way."

At their core, however, Andrés says his restaurants should be an oasis for diners. "The word [restaurant] has many origins, but one of them will be from 'restore' or 'restoration'. You went to the restaurant to restore yourself, sometimes physically, emotionally and spiritually in the old days. I believe in certain ways restaurants are that still today."

Andrés also sees food as a powerful vehicle for change. Outside the kitchen, he found a calling in the development of WCK following the massive 2010 earthquake in Haiti, which killed more than 200,000 people. Already chairman of Washington DC non-profit DC Central Kitchen, Andrés saw an opening to create an international organisation focused on direct aid through food.

"I'm a very impatient guy, and I don't like to see the things on the side-lines. I like to be in the game – boots on the ground," he says. "[In Haiti], we saw the devastation in an already very poor country, and I said, 'let me go not so much to help, let me go to start learning', and slowly I began learning that it doesn't require more than just the willingness to make it happen."

Since 2010, WCK has served more than 350 million meals around the world by partnering with on-the-ground organisations, and activating a network of local restaurants, food trucks and emergency kitchens. In 2019, Andrés was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian work.

The key to making a difference, says Andrés, is having the confidence to believe you can make an impact in a time of need right where you are – and seizing the opportunity. "You don't need to go to another continent, you can do it in your own country," he says.

Simply, he believes any step towards action creates a tangible impact. Since childhood, he's seen the fruits of even the smallest moves. "I think all my life I've been very lucky. My mom, a nurse, was always like, 'let's help everybody'. I mean, everybody," he says. "We'd be helping a family going through a hard time, helping a friend because he got injured ... Anything we do, even if it's very little, is more than absolutely nothing."