Are community currencies a better way to shop?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCurrencies like the Bristol Pound support local retailers and build a sense of community, proponents say – and now some are going digital.

“Bristol Pounds stand for so many things that we do. It just made sense,” says Stacey Fordham, standing amid artisan cooking oils, natural wellbeing products and dispensers for pasta, grains and pulses at her zero-waste shop, Zero Green in Bristol, England.

Her store is one of around 500 businesses in the city that accept the Bristol Pound, Britain's largest community currency.

What’s a community currency? It’s a special, local currency that can only be used within a certain locale at shops or other businesses that have signed up to accept it as an alternative to the official, national currency, with the goal of encouraging spending in the local economy. This can either encompass a whole town, or in the case of a currency like the Brixton Pound, just one London neighbourhood, and can be bought at a rate equivalent to the national British pound. There are thousands of community currencies in the world and the concept has been around for decades, and in the past couple of years, they’re becoming more popular as more have become digital.

Norman Miller

Norman MillerCommunity currencies are seen by proponents as an innovative tool to help local trade flourish against the trend to globalisation. Other benefits can include providing a method for people without access to paid employment to earn 'money' through charitable or other community work, as well as providing a medium for a specific town or region to express its individual identity in a way national currencies do not. But community currencies have yet to really infiltrate the mainstream – sometimes stymied by a naïve attitude to running costs, or failure to provide digital forms that chime more with modern ways of spending. Now, however, various currencies are tackling these issues in different ways worldwide.

Each community currency reflects a desire to handle community-based transactions in a different way. The UK's current wave of community currencies sprang from the anti-globalisation Transition Network movement in 2006, inspiring the 2007 launch of the Totnes Pound in the market town in Devon in England. The impetus continues today, with new city-based currencies mooted for Glasgow, Cardiff and Birmingham, all in the UK.

For Fordham, the Bristol Pound helps forge a special link with local communities while boosting business. Though each community currency reflects its locale, a common aim is to support local economies by providing a currency that, because it only has value within that community, circulates around that community rather than flowing away. 'Keeping money local' is a core theme; multiple studies have shown that local independent retailers recirculate far more money into their communities than chains (2.6 times the amount, according to one Canadian study).

While some community currencies must be purchased at local issuing points using the national currency, others give citizens a chance to 'earn' income through good deeds like charity work – something which helps explain why these currencies have often flourished in areas and at times where many were jobless.

“There is a strong relationship between unemployment and the size of complementary currencies,” says German economist Christian Gelleri, who founded the community currency called Chiemgauer that can be used in in Germany’s Bavaria region. “One successful example in 2019 was the Sardex in Sardinia, with more than 3,000 businesses and a turnover of nearly €50m ($54.7m, £44.4m). The unemployment rate there was 15%. We had €6.3m turnover in [the currency] Chiemgauer, with an unemployment rate of 1.9%.”

Oli Scarff

Oli ScarffLocal culture, local needs

It’s not just about local economics, however; community currencies can play an important role in celebrating local culture. In Brixton, south London, for example, around 150 outlets take colourful Brixton Pound notes bearing diverse icons with ties to the community. David Bowie emblazons the Ten Brixton Pounds in his Aladdin Sane persona, basketball star Luol Deng (who grew up in Brixton) gazes from the Five, while the Twenty honours World War Two secret agent Violette Szabo.

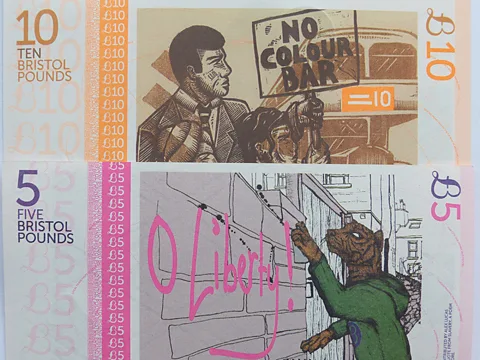

Commissioned artwork full of local references has also been a feature of the Bristol Pound since its 2012 launch; its current One Pound note, for example, bears local Bristol artist Radley Cook's illustration of fierce 2011 protests against a supermarket chain opening in one bohemian neighbourhood. In the medieval English town of Lewes in Sussex, 60 miles (96km) south of London, community currency notes celebrate historical events like the 750th Anniversary of the Battle of Lewes, but also the opening of the Depot art-house cinema, plus a 2013 music festival appearance by British rock band Mumford & Sons.

Because only the Bank of England is permitted to print legal tender in England (with Scottish notes issued by banks there), community currency bank notes are technically vouchers that local retailers can agree to accept. They are also legally required to expire after a certain date; the current edition of Bristol Pounds, for example, will expire on 30 September 2021. This spurs fresh designs, while encouraging people to spend rather than hoard.

In some places, community currencies can also be used to better distribute spending across periods of time. Kenya's hyper-local Bangla Pesa is used in just one area of Mombasa to even out buying power in a place where disposable incomes can fluctuate widely – for example, just after pay day, as seen in this BBC report from 2018.

Each business in the currency network received 400 Bangla Pesa, which they agreed to use for local goods and services. These are then used to continue to make local transactions when Kenyan shillings are in short supply. So a bicycle operator in a trading dip can still buy groceries using Bangla Pesa, and the grocer can use them for something else another time.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe world’s longest-running community currency – Switzerland's WIR (Wirtschaftsring-Genossenschaft; ‘wir’ also being an abbreviation for ‘we’ in German) – also has its roots in hard times. Created in 1934 as war loomed and Swiss unemployment surged, the WIR today has more than 50,000 members (17% of the total number of Swiss businesses) with annual revenues of €1.5bn. A 2009 study illustrated how the WIR provided extra local economic stability during national recessions – simply put, when individuals found themselves short of Swiss francs, they could continue buying products from businesses who accepted the WIR.

Can they go mainstream?

Community currencies come and go all the time. So why don’t more cities and regions around the globe use them? After all, some local currencies have also now added a convenient digital element – the Bristol Pound, for example, now also has associated Google and Apple payment apps to complement the physical bank notes.

One problem that has felled some community currencies is finding a suitable way to cover operating costs. The WIR solves this via a transaction fee – 0.06% for members and double for non-members – paid in Swiss francs, plus interest on loans taken out in WIR. Canada's Calgary Dollar funds itself by paying its employees partly in Calgary Dollars, as well as receiving fees from government and businesses.

In the US, however, the annual $300,000 cost of keeping Philadelphia's Equal Dollar in circulation eventually led to its closure in 2014 – albeit after an impressive 19 years paying locals in exchange for goods, services and labour.

Cost aside, some might argue that community currencies will always have a limited reach; that they principally appeal to a more privileged section of a community with ideals and resources to seek out places to spend 'local money' rather than opting for the convenience (and potentially lower prices) of the nearest chain outlet.

Easy-to-use digital versions of community currencies – like- the option added by Calgary in 2018 may, however, provide a vital new boost. “Calgary is proud of our beautiful printed currency – but since the launch of the digital currency the convenience of making payments from mobile device apps is proving far more popular,” says the currency manager Gerald Wheatley.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn England, the northern city of Hull created the world's first digital-only local currency in 2018, inspired by blockchain technology. HullCoin is earned via 'good works' with local organisations, then redeemed for discounts of up to 50% on goods and services. Retailers can re-issue HullCoins to employees or loyal customers – or donate them back to community groups for re-issue.

Diana Finch, who oversees both the Bristol Pound banknotes and the digital Bristol Pay complement introduced in 2018, says the community currency has “achieved a lot in raising awareness of the problems associated with a globally dependent economic structure”. It’s also been a great learning opportunity for those working in the field of alternative currency and economic systems, she adds.

As for Stacey Fordham, the Bristol Pound continues to embody more than just a novel way to do business. “It has to do with being part of something that links so many people in Bristol. Taking the Bristol Pound brings like-minded people to the shop. And it's a wide range.”