Can price hikes by businesses ever be justified?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPeople hate price gouging. Can businesses navigate supply chain stress and changing consumer behaviour without raising prices – and should they?

From eggs to yeast, shoppers around the world have been encountering empty grocery store shelves during the Covid-19 pandemic. Many have changed their shopping patterns as a result, visiting smaller shops, planning shopping trips for off-peak hours, replacing the usual staples, buying as a group or – in some cases – paying higher prices.

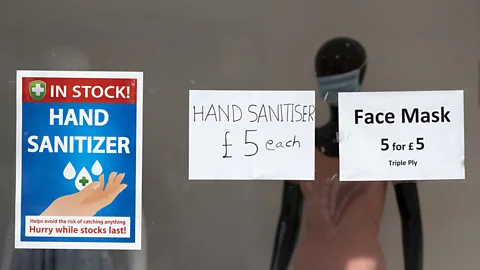

Certain items have surged in both demand and cost. There are reports of small hand sanitiser bottles selling for €10 in Ireland and small boxes of face masks selling for more than $200 in the US. Shoppers in the UK are outraged by increased prices of meat, lentils and rice. But some people argue that price increases during crises, though they instinctively feel unfair and exploitative, might be justifiable.

A key difference is between price increases which reflect the higher cost of doing business during extraordinary circumstances, and price gouging, which is one type of profiteering. Though price gouging isn’t a technical economics term with a precise definition, it’s usually understood to refer to exorbitant price increases of essential goods, often following shocks or in crises.

Yet it can be challenging to identify a reasonable mark-up that reflects businesses’ higher risks and costs, as well as to pinpoint where in the supply chain the cost increases are hitting hardest. This is especially tough amid the explosion in loosely regulated, border-spanning online sales.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFrom price hikes to price caps

The good news for high-income countries is that the food supply system is generally flexible and resilient. “The food supply chain operates on a ‘just in time’ basis,” explains Richard Sexton, an agricultural economist at the University of California, Davis. “The retail food stores have no capacity to hold excess inventories and no interest in doing it.”

The shortages in the early days of the pandemic were mainly due to panic buying, especially of non-perishables like tinned beans. “When we get an unexpected demand spike like the hoarding due to coronavirus or hoarding that might precede a natural disaster such as a hurricane, the supply chain cannot readily adjust to replenish supplies,” Sexton says.

In many cases these delays will be a temporary phenomenon as manufacturers and distributors catch up. Effects on food prices will vary, but some commodities (like sugar) are dropping in price while others (like rice) are increasing, due to changing demand and some countries’ export restrictions. These global food price changes are unlikely to be passed onto consumers immediately.

But retail delays and customer stockpiling (which has subsided in the UK and more widely) mean some goods appear to be in short supply in the short term. This creates conditions in which retailers might put up prices and consumers might be inclined to pay more. One possible response is capping prices for day-to-day essentials.

Sexton is in favour of limiting purchases of some products, something many large supermarket chains have implemented, but price caps are another story. “Price caps – below a price that would clear the market – would only exacerbate shortages.” People would be able to hoard low-cost goods, and suppliers would have less incentive to pump out more low-margin products. Sexton notes that this can be a hard message to swallow: “As a society, nobody wants to see anybody profiteering from an international tragedy, so the idea of limiting that is very appealing. But in a lot of cases, the impact of price increases is to call forth more supplies.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMatt Zwolinski, a political philosopher at the University of San Diego, agrees that higher prices have the vital function of signalling to manufacturers that it’s worthwhile to create more supply. Otherwise it may not be worth disrupting their businesses and taking risks during a health emergency. “Price increases both limit demand and increase supply. And for a lot of goods, that’s exactly what we need,” Zwolinski argues.

When it comes to grocery deliveries, for example, he says we should “pay drivers more, charge customers more and get the supply up to a level where it’s sufficient to meet the massively increased demand”. He believes that this applies even in the case of essential medical equipment like ventilators (although desperate US states have engaged in bidding wars for ventilators and other critical equipment).

In general, many economists believe that price caps aren’t effective, and could even be counterproductive, in emergencies. They might encourage fighting and overcrowding in stores as people compete for scarce-yet-affordable goods. If price hikes lead people to conserve in-demand goods more carefully, price caps can worsen shortages. A black market, with even higher prices, may be likely to emerge.

Yet Nobel Prize Laureate Paul Krugman has bucked this common belief among economists by writing, “if disasters are followed by a free-for-all, with very high prices for essentials, the stakes of inequality become much higher. Those who can’t afford high prices face extreme privation, even death, while those with sufficient wealth face no more than inconvenience.”

This is especially significant for items whose use is beneficial for everyone’s health, not just the individual’s. South Korea, one of the rare bright spots of pandemic response, has reduced the market price of face masks in addition to limiting the number each person can buy. This has required a high level of coordination to avoid rationing, a government push to ramp up production of masks, and pharmacies willing to lose money on the sale of an important public good.

So price caps can promote public health. But, unless governments are willing to provide substantial support, they may not be able to keep businesses afloat.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTough decisions facing small businesses

It’s at the small business level that fluctuations in both supply chains and consumer patterns can be felt most keenly.

Janine Tozer runs Not Just Pets, two pet supply shops in Frome and Bath, in England. She explains that some items “are becoming almost impossible for us to purchase from our suppliers”, and sales have suffered as a result. So far, though, supply prices haven’t increased significantly, and her business is somewhat fortunate in that there are plenty of substitutes for customers’ first-choice items.

Tozer understands businesses’ temptation to raise prices of sought-after products as a buffer against all the uncertainty. That uncertainty – about when government support will kick in, about whether people will once more buy the pet accessories that generate greater profit than pet food, about whether customers will return after lockdown finally ends – is the hardest part.

As infection rates climbed across the UK, some MPs and councils investigated reports from residents of price spikes in local retailers. Some have been named and shamed, particularly on social media. Andrew Goodacre, CEO of the British Independent Retailers Association (Bira), says he has no support for businesses that are seen to be exploiting consumer demand.

But naming and shaming isn’t a structural response. Bira’s members have a cash liquidity problem that ripples up and down the supply chain. Many hardware stores, for instance, which are considered essential businesses in the UK, can’t afford to pay for delivered supplies due to plummeting sales, and thus manufacturers can’t guarantee further supply. The government support to small businesses will help, but not all businesses will be able to hold on until then – or survive even with the assistance.

Consumer anger might be reduced if retailers better explain the reasons for their price hikes, if any. Tozer acknowledges that if wholesale prices were to rise substantially, without a good explanation from suppliers, she would have to pass on some of those higher prices to consumers. She would prefer to limit quantities per customer rather than raise prices, but in any case she would inform customers of the reasons for pricing changes, rather than letting them assume the worst.

“We always try to convey anything that changes within the business to our customers,” Tozer says. “I think being transparent is the only way to go especially in the current situation because people want to know what’s going on.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShaping regulation – and reputation

Yet all the transparency in the world may not be enough for consumers worried by the state of their finances. People are instinctively repelled by anything they perceive as price gouging, and moral psychology research suggests that this is a powerful feeling.

Apsana Begum, a member of parliament representing the densely populated East London area of Poplar and Limehouse, says she’s heard plenty of people vent about high prices. Especially in the early days of the crisis, it was hard for people to pay two or three times the normal prices for toilet roll and hand wash at smaller businesses. “This was actually causing a lot of anger locally, and understandably so.”

Begum is sympathetic to the small businesses struggling to keep the lights on and applauds the many traders that have not sought to profit from the emergency. Some butchers, especially, report increased prices from suppliers and are just trying to pay the bills. Other costs that may have increased, for retailers of all sizes, include hazard pay and more overtime for existing staff, the hiring of temporary employees, higher transport costs and purchases of more protective and cleaning equipment (even though some governments are covering portions of these expenses).

Yet Begum believes that overall the government needs to do more to safeguard a sense of community responsibility among retailers. Last month she tabled an early day motion (a motion submitted for parliamentary debate) calling for stronger government action against price hikes. Begum urges more analysis of how businesses in different categories, including suppliers and wholesalers, are affected by the crisis. Also helpful, she says, would be further resources directed to the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), which is fielding complaints from consumers and pleading with businesses not to price gouge.

Nicole Kar, head of UK competition at the law firm Linklaters, believes that this motion could lead to action if it’s accompanied by a groundswell of people complaining on social media, consumer advice organisations campaigning and – especially – further government consideration of “wartime” measures against profiteering. In many countries, she explains, price gouging is not in itself illegal. In the UK, only monopolistic practices or collusion between businesses would typically be illegal.

France has capped retail and wholesale prices of hydroalcoholic gels for sanitising hands. China has prohibited unnecessary stockpiling of some protective medical equipment and food. Australia has made it illegal for retailers to purchase items like goggles and resell them for a mark-up of more than 20%. US states have a patchwork of laws, but California’s anti-price gouging statute limits price increases to 10% if a state of emergency is declared.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesKar says that so far South Africa has gone furthest. Its government has calculated an unfair or excessive price as being higher than cost increases and an average mark-up between December 2019 and February 2020. A “dominant firm” that contravenes these laws could face a fine of 10% of annual turnover, or a representative could face up to 12 months in prison. This kind of government action is ultimately more effective than the slow case-by-case process of regulators receiving and responding to complaints. “We haven’t seen any actual enforcement at the moment,” Kar says of the CMA in the UK, which is likely to resort to writing warning letters and making examples of high-profile profiteers.

It’s often very difficult, however, to identify exactly where in the supply chain the price increases are stemming from, and it’s especially hard to police online sales – where price hikes have been noted by consumer groups. These price gouging laws and warnings also typically won’t apply to the small businesses where many of the price hikes have been seen, because the laws often focus on “dominant” companies, as in South Africa. Agricultural economist Sexton explains of smaller firms: “They’re being squeezed more by the shortages than the big supermarkets, simply because they’re less important customers for the distributors.”

Some business owners, meanwhile, might argue that if they are working harder to serve communities despite potential health risks, they perhaps deserve to earn a bit more and potentially pay their staff more. As has been pointed out, those currently keeping nations running are often on the lowest incomes.

Overall, economists and others, including the people interviewed for this article, tend to agree on one point: price gouging comes with significant risks to reputation. While this is especially likely to keep large chains in check, smaller businesses can’t afford to let their reputations take a dive either. As Tozer of Not Just Pets puts it: “I just wonder… if you’ll retain the custom in the future if you do this, because people might see you as being unscrupulous.” She believes that to keep customers in the long run, it’s important to avoid raising their ire.

Surely customers would agree with that as well.