The new island solving a Nordic housing crisis

Copenhagen City & Port Development

Copenhagen City & Port DevelopmentThe city of Copenhagen often tops global rankings for quality of life. But its growing popularity has put a strain on housing supply, so city planners are working on an bold solution.

Benoît Derrier

Benoît DerrierAccommodation availability and affordability is a major issue in Denmark. The average household spends more than a quarter of its disposable income on housing costs, one of the highest proportions in the western world, according to the OECD.

Rents and mortgage costs are especially high in Copenhagen, driven up by more than 10,000 people a year moving to the city to work or study, both from elsewhere in Denmark and around the world. The current population is around 780,000 and predictions suggest it will increase by a further 100,000 by 2025.

Copenhagen City & Port Development

Copenhagen City & Port DevelopmentPlanners propose building a new island, Lynetteholmen, close to the city centre to try and address the housing crunch. The island will provide 35,000 new homes, with at least 20% earmarked as affordable rental housing for students and lower earners. Cycle paths, a new subway line and a highway will connect the island to the mainland.

Lynetteholmen will also mitigate the effects of rising sea levels due to climate change, planners say. By increasing the land mass around Copenhagen, and thanks to strategically designed banks on the island, it will help prevent flooding in the city centre.

Construction is expected to start in 2035 after a long public planning process and be complete by 2070. The project is set to cost $3bn (around 20bn Danish kronor). It will be financed by the City of Copenhagen and the Danish government, although politicians say they will source the money by selling land and housing, rather than asking taxpayers to contribute.

(Reporting by Maddy Savage, video shot and edited by Benoit Derrier)

Benoît Derrier

Benoît DerrierLynetteholmen is set to be one of the biggest urban development projects since the 1990s, but some are concerned about packing too many residents into the city centre and say further regeneration will be needed on the outskirts too as Copenhagen’s population swells.

Professor Ellen Braae, an architect and urban development professor at the University of Copenhagen, says while she’s “excited” about the project, she believes it could pose infrastructure challenges; although the goal is sustainability, many residents are likely to be affluent car-driving commuters. She also feels diversity should be prioritised, so the island does not become an enclave for higher earners.

There are also mixed views on the impact Lynetteholmen will have on the Refshaleøen, a hub for artists, foodies and innovators which will be connected to the new island via a bridge. Braae fears its identity could change if investors home in and the vibe becomes more corporate.

But others believe it could boost the local economy. “For us as a business, [it] would be one of the best things that could happen,” says gourmet fast food stall owner Dragos Sintimbrean, 29. “And citizens need a place to live!”

Benoît Derrier

Benoît DerrierAlthough Lynetteholmen is the biggest and most complex project of its kind in Danish history, it’s not the first time Danes have created artificial islands to live and work on. One of the trendiest districts in the city, Christianshavn, is a man-made island that was commissioned by King Christian IV in the 17th Century. It was built on top of thousands of wooden poles.

Many other parts of the capital were also created by building up from the seabed, including Islands Brygge, a harbourfront area in the centre, Kalvebod Brygge in the former meatpacking district, Vesterbro and large parts of Nordhavn in northern Copenhagen. More recently, Peberholm island was created as a crossover point for part of the Öresund bridge, which connects Copenhagen to Malmö in southern Sweden.

The first phase of Lynetteholmen’s construction will involve putting an iron cage on the seabed to mark the island’s perimeter and filling it with soil dug up during other infrastructure projects in Copenhagen .

Benoît Derrier

Benoît Derrier“I think it makes a lot of sense. If you look back in Copenhagen’s history, a lot of the islands have been built – we just don't realise it anymore. And I think I would rather have them building a new island than tearing down the old historic buildings and building new apartments.”

Mikkel Moller Jensen, digital sales manager.

Benoît Derrier

Benoît DerrierDenmark has a reputation for innovative architecture and green city planning. Copenhagen mayor Frank Jensen argues that engineers, architects and city officials will keep sustainability in focus while working on the Lynetteholmen project.

“It’s very important for me that we will have a Metro line to the new island. And then we will make it a bike-friendly area of the city like other parts of Copenhagen.”

The Danish capital already has 375km of cycle tracks; traffic lights are programmed to favour cyclists during rush hour. Planners will also prepare for more futuristic types of transport like autonomous boats and self-driving cars.

“You have to have a master plan, of course, but you have to make it flexible to adapt for changing elements when it comes to technology, energy supply and standard of living,” says Soren Tegen Pedersson, director of planning for Copenhagen City Council.

Benoît Derrier

Benoît Derrier“I think it’s a nice idea, but I don’t buy it. I don’t believe the politicians when they say the new island will be for everyone. I can’t see how – when other housing is so expensive – that this is going to be an affordable price. There’s so many people that want to live in Copenhagen.”

Stephanie Norholm Nielsen, nursing student.

Benoît Derrier

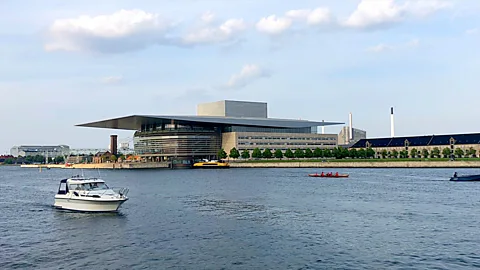

Benoît DerrierAs well as being an increasingly popular place to live, Copenhagen is also a magnet for tourists, who come to visit attractions such as the Little Mermaid statue, the opera house and the colourful 17th Century townhouses along Nyhavn waterfront.

According to figures from the city council, the majority of Copenhageners support increased tourism and 81% of locals believe the city should continue to be promoted to attract more visitors.

The city’s mayor says that building Lynetteholmen fits into a wider strategy designed to get visitors to explore different parts of the Danish capital when they visit.

“With growing tourism, we need to invite the tourists – the guests in our city – to go to new spaces, new places like the coming Lynetteholmen.”

URBAN POWER Architecture & Urban Planning

URBAN POWER Architecture & Urban PlanningThere are also plans to build nine other islands in an industrial district around 10km south of the city centre. The idea is to form what has been described by supporters as a “floating Silicon Valley”, designed to attract companies in the tech, pharmaceutical and life sciences sectors. These islands will be given the collective name Holmene.

The project was officially launched by the Danish government in January 2019 and will be overseen by the local municipality, Hvidovre, rather than Copenhagen City Council.

Planners hope the new islands will create around 12,000 jobs and encourage more sustainable housing in the area. But while there are hopes that construction could get going as early as 2025, so far few companies have signed up to take part in the project.

Benoît Derrier

Benoît Derrier“We want to be a city that is inclusive, with all kinds of opportunities… We are building a city for tomorrow.”

Soren Tegen Pedersson, director of planning for Copenhagen City Council.