The curious origins of the dollar symbol

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite its ubiquity, the origins of the dollar sign remain far from clear, with competing theories touching on Bohemian coins, the Pillars of Hercules and harried merchants.

As we head into 2020, we're running the best, most insightful and most essential Worklife stories from 2019. Read all of the year's biggest hits here.

The dollar sign is among the world’s most potent symbols, emblematic of far more than US currency.

It’s shorthand for the American dream and all the consumerism and commodification that comes with it, signifying at once sunny aspiration, splashy greed and rampant capitalism. It’s been co-opted by pop culture (think Ke$ha when she first started out, or any number of fast-fashion t-shirts) and borrowed by artists (Salvador Dali fashioned a moustache from it, Andy Warhol rendered it in acrylic and silkscreen, creating an iconic body of work that itself now sells for $$$).

You might also like:

It’s used widely in computer coding and it provides money-mouth emoji with its dazed eyes and lolling tongue. Yet despite its polyglot ubiquity, the origins of the dollar sign remain far from clear, with competing theories touching on Bohemian coins, the Pillars of Hercules and harried merchants.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe dollar’s baby sibling, the all-but-worthless cent, is logically represented by a lowercase ‘c’ with a line through it, but there’s no ‘D’ in the dollar sign. If you had to find letters lurking in its form, you might spy an ‘S’ overlain with a squeezed, bend-less ‘U’ providing its vertical strokes. In fact, this accounts for one of the most popular misconceptions about the sign’s origins: it stands for United States, right?

That’s what writer and philosopher and famed libertarian Ayn Rand believed. In a chapter in her 1957 novel, Atlas Shrugged, one character asks another about what the dollar sign stands for. The answer includes these lines: ‘for achievement, for success, for ability, for man's creative power—and precisely for these reasons, it is used as a brand of infamy. It stands for the initials of the United States’.

It seems that Rand was wrong, not least because until 1776, the US was known as the United Colonies of America, and there are suggestions that the dollar sign was in use before the United States was born.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe British pound sign has a history going back 1,200 years, when it was first used by the Romans as an abbreviation for ‘libra pondo’, the empire’s basic unit of weight. As any amateur astrologer will tell you, libra means scales in Latin, and libra pondo literally translates as ‘a pound by weight’.

In Anglo-Saxon England, the pound became a unit of currency, equivalent to – surprise, surprise – a pound of silver. Vast riches, in other words. But along with the Roman name, the Anglo-Saxons borrowed the sign, an ornate letter ‘L’. The crossbar came along later, indicating that it’s an abbreviation, and a cheque in London’s Bank of England Museum shows that the pound sign had assumed its current form by 1661, even if it took a little longer for it to become universally adopted.

The dollar, meanwhile, has a far shorter history. In 1520, the Kingdom of Bohemia began minting coins using silver from a mine in Joachimsthal – which roughly translates from German into English as Joachim’s valley. Logically if unimaginatively, the coin was dubbed the joachimsthaler, which was then shortened to thaler, the word that proceeded to spread around the world. It was the Dutch variation, the daler, that made its way across the Atlantic in the pockets and on the tongues of early immigrants, and today’s American-English pronunciation of the word dollar retains its echoes.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite the currency’s relative youthfulness, however, there is no straightforward answer to the question of where the dollar sign sprang from. Nobody seems to have sat down to design it, and its form still fluctuates – sometimes it has two lines through it, increasingly just the one. Not that there aren’t plenty of competing hypotheses. For instance, circling back to the idea that there’s a U and an S concealed within its form, it’s been suggested that they stand for ‘units of silver’.

One of the most esoteric origin stories links it back to the Bohemian thaler, which featured a serpent on a Christian cross. That itself was an allusion to the story of Moses winding a bronze snake around a pole in order to cure people who’d been bitten. The dollar, so it’s said, derived from that sign.

Yet another version centres on the Pillars of Hercules, a phrase conjured up by the Ancient Greeks to describe the promontories that flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. The pillars feature in Spain’s national coat of arms and, during the 18th and 19th Centuries, appeared on the Spanish dollar, which was otherwise known as the piece of eight, or peso. The pillars have banners twined around them in an S-shape and it doesn’t take much squinting to see a resemblance to the dollar sign.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe most widely accepted theory does in fact involve Spanish coinage, and it goes like this: in the colonies, trade between Spanish Americans and English Americans was lively, and the peso, or peso de ocho reales, was legal tender in the US until 1857. It was often shortened, so historians tell us, to the initial ‘P’ with an ‘S’ hovering beside it in superscript. Gradually, thanks to the scrawl of time-pressed merchants and scribes, that ‘P’ merged with the ‘S’ and lost its curve, leaving the vertical stroke like a stake down the centre of the ‘S’. A Spanish dollar was more or less worth an American dollar, so it’s easy to see how the sign might have transferred.

As with everything American at the moment, there’s a partisan dimension to the debate about the dollar sign’s ancestry: for duelling political reasons, one faction favours the idea that it’s homegrown, another that it was imported.

It’s certainly ironic – though hardly surprising – that a symbol so intrinsic to America’s national character might have its roots in another country altogether. But regardless of how it came to be, it is certainly an American invention: he may not have been its sole creator, but the correspondence of Irish-born Oliver Pollock, a wealthy trader and early supporter of the American Revolution, has led him to be often cited by historians as its originator.

Getty Images

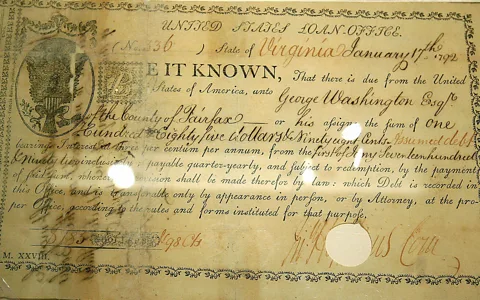

Getty ImagesAnd as for the first printed dollar sign, that was made on a Philadelphia printing press in the 1790s and was the work of a staunch American patriot – or at least a vehemently anti-English Scotsman – named Archibald Binny, who’s today remembered as the creator of the Monticello typeface.

Of course, if you really want to tumble down a rabbit hole of mysterious symbolism, try looking into the origins of the design of the American dollar bill. Eye of Providence, anybody?