If your boss asked you to take a polygraph test, would you?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a workforce that's filled with employers wanting to keep tabs on you and track your data, just how far could they go? And how comfortable would you be with it?

In the widely-watched hearings last week on the confirmation of US Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, the word “polygraph” came up more than once.

US President Donald Trump has nominated the senior judge for a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court – America’s highest court, with the final word on controversial topics ranging from abortion to gay marriage. But sexual assault allegations have slowed his confirmation. It’s been during Senate committee hearings that polygraphs have been mentioned.

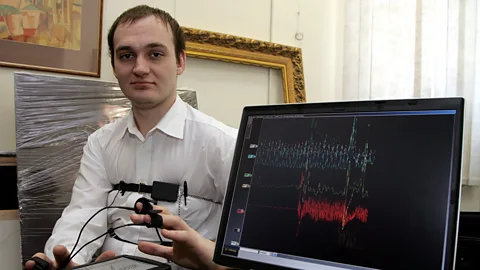

These are the “lie detector” tests that are supposed to flag when someone’s fudging the truth, based on physiological reactions that might be triggered as they’re being asked questions, like a spike in blood pressure.

Polygraphs have come up because Dr Christine Blasey Ford submitted to a polygraph test following her accusation that Kavanaugh assaulted her when she was in high school. Kavanaugh, who denies the allegation, has not yet taken a polygraph test.

Polygraphs are often used in the US in criminal investigations or in intelligence gathering by the police or government agencies. The Kavanaugh hearings, meanwhile, have been described by senators involved in the hearings as a high-profile “job interview”.

In many countries, administering polygraph tests as part of a job interview process or in other contexts is illegal. But hypothetically – in a world full of data trackers and employers scrutinising your every move – if your potential new boss asked you to complete a polygraph test, would you? If they’re looking for the absolute best person for the job, beyond a shadow of a doubt, why not?

What’s the big deal if you’ve got nothing to hide?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIs it even legal?

That depends on where you live.

In many countries, it isn’t. In the US, for example, they’ve been prohibited in the private sector workplace since 1988 under the Department of Labor’s Employee Polygraph Protection Act. (There are exceptions, of course, especially if you’re interviewing for a position in the government, security or intelligence communities.)

In other places, there aren’t laws in place to protect employees from polygraph screenings, as in South Africa. They’re also allowed in job applicant screenings in Israel. Meanwhile, Kenya’s using them as part of its plan weed out corrupt politicians.

Polygraph tests have existed since 1921, and are still widely used.

“They can be very helpful in identifying issues and concerns that warrant further investigation and follow up,” says Jeffrey Feldman, a professor at the University of Washington School of Law in Seattle. “A negative result might not prompt you to throw out the candidate, but it reasonably would prompt you to investigate further.”

But whether or not polygraph tests are illegal in the workplace doesn’t really get at the bigger issues that could make them problematic in such a context, experts say.

“Basically, if you are hooked up to a lie detector, it is likely to signal to a potential employee that your employer does not trust you,” says Andre Spicer, professor of organisational behaviour at the Cass Business School at City University London. Applicants stand to lose “their dignity and sense of trust in their future employer”.

RIP, trust?

Doug Williams is a former police officer and certified polygraph administrator in the US who says he’s administered over 6,000 polygraph tests. He’s written a book and taught classes on how to beat a polygraph test, and even served two years in prison in 2015 for being caught in a sting operation when he helped undercover agents beat a lie detector test.

Why has he taken such a defiant stance against polygraph testing? To help people protect themselves, he says.

“It’s a multi-billion-dollar scam and it destroys [the] lives of literally millions of people,” he says. It’s “no more accurate than the toss of a coin”. Besides the manual he wrote, he says the internet is awash with tips on how people can relax themselves to control the physiological responses that supposedly hint when someone is lying, such as a racing pulse or sweating.

But in his decades of giving polygraph tests and studying them, Williams says the device is little more than a tool to intimidate people, which could lead to problems if they ever ended up in a workplace.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s “a psychological billy club [truncheon] that coerces and intimidates a person into a confession. It scares the hell out of people,” he says. “I would never work for a company that requires polygraphs, because they’re starting the entire relationship off as an adversarial proceeding.”

So, are bosses using polygraph tests more as an assessment tactic rather than a way of finding truthful answers to difficult questions? Or is it more a measure of whether candidates can handle this kind of extreme stress?

Susan Stehlik is a professor of management communication at New York University. She likens office polygraphs to a “stress test” for young applicants she observed as an independent consultant for a major hedge fund.

“They’d say to a student, with four or five senior people in the room, give me the square root of 563,000,” she says. She says their rationale was: “’Well, if you’re going to be a trader, you need to know numbers.’”

But Stehlik says such an obscure trial doesn’t actually give any clues about how people will perform on the job.

Williams thinks the only thing an office polygraph could prove, besides whether someone is nervous or embarrassed and has a fast heart rate and fails the test, would be whether someone is a hardened liar who could pass the test without moving any needles.

A toxic work environment

Stehlik likens an adoption of polygraph screening to the widespread mandatory drug tests in the cocaine-fuelled 1980s, a big push by then-US President Ronald Reagan. She thinks it’s crucial for businesses to ask themselves: why are you doing this? Because there was one problem employee? Will everyone have to take it?

“It’s just adding more to the distrust we have between employer and employee,” she says. Moreover, she adds, what do you do with the people who fail? Rehab? Fire them? A slap on the wrist?

These kinds of tests could allow managers to exercise more control over potential workers, says Dan Cable, professor of organisational behaviour at London Business School.

“It gets squirrely when you start asking people about the life choices that they’ve made that aren’t work-related.

“You don’t know what they’re going to ask you,” Cable says. “It’s like Meet the Parents. The surprise attack part of it is the big difference,” he says.

But the polygraph can actually help employees in some cases, says Australian Polygraph Services director Steve van Aperen. In Australia, workplace polygraph tests are legal in most states – but only if the employees consent.

Most people might think of a lie detector test being used by bosses to unearth criminal or unethical behaviour, it can also protect workers from false allegations.

“I get more calls from employees who say ‘look, I’ve been falsely accused of this, it’s not true – I want to tell the truth,’” says van Aperen.

Studies show that if you refuse to reveal information about yourself, it could backfire. A 2015 Harvard University study showed that in seven experiments in which participants in an online survey were presented with questionnaires from hypothetical mates and employees who withheld unflattering information about themselves – drug use, bad grades, sexual history – the participants judged them more harshly than those who confessed to bad behaviour “across decisions ranging from whom to date to whom to hire”.

The study showed that it might be human nature to be more suspicious of people reluctant to divulge personal details than of people who disclosed bad behaviour up front. “When faced with decisions about disclosure, decision-makers should be aware not just of the risk of revealing,” the study says, “but of what hiding reveals.”

How much should employers know about you?

We live in a world where your boss can track your every move and monitor your data. Some people may feel they have nothing to hide – they may not care about their privacy or about taking a lie detector test. They might shrug and think, I really need this job.

But it’s worth considering what would happen if polygraph tests at work became more widespread.

“If most employees agree to take a lie detection test, then there would naturally come to be some suspicion of those who refuse to take it,” posits Nick Bostrom, ethics professor at the University of Oxford. “Refusal would send a bad signal – it suggests you have something to hide.”

As for the results themselves? There’s no hard data on the accuracy or success rate of polygraph tests. Many courts don’t allow the results to be submitted as evidence.

“Polygraph tests are quite unreliable, but a weak clue might be better than no clue” in the minds of some employers, Bostrom says. “Results need to be combined with other sources of evidence, and not trusted blindly.”

--

Bryan Lufkin is BBC Capital’s features writer. Follow him on Twitter @bryan_lufkin.

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, please head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

{"image":{"pid":""}}