Can festive cheer boost your language skills?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMaking yourself understood in a second language could be all about getting rid of anxiety, writes Joseph Pearson.

If you’re failing to make yourself understood in another language this holiday season it appears a drop of Dutch courage may not be such a bad idea.

A recent study from the University of Maastricht suggests an alcoholic drink – and the increased confidence that goes with it – can actually improve your performance in your second language.

Slurring your words?

A group of fifty Germany exchange students studying in the Netherlands were given either a vodka mixed with bitter lemon, or a glass of water. Once blood alcohol content levels had peaked – at about the same level as would be expected after drinking a pint of 5% strength beer – they were asked to argue for or against, animal testing in Dutch for a few minutes with an experimenter. The conversation was then recorded and their performance analysed by native Dutch speakers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe results were a surprise to the Maastricht team: They showed that those who had drunk a low dose of alcohol had higher ratings when arguing in a foreign language than those who drank water.

“We started out doing this research with the presumption that people would only subjectively perceive they would get better [at speaking foreign languages], and that the objective data would tell them no they don’t,” says Jessica Werthmann, co-author of the study. We were surprised that it turned out to be exactly the opposite”.

The results underline something many expat workers know from their own experiences with colleagues. As Kate Price, a Brit living in Berlin, explains about speaking German: “There is definitely a parabola – one drink, getting more confident; two drinks, feeling eloquent; but three drinks, probably starting to slide down the other side of the curve”.

The study’s authors are cautious, however, about drawing broad conclusions. This is a small study, whose findings need to be replicated. Werthmann questions whether they would obtain the same results with languages not as closely related as Dutch and German.

“What we did find is that alcohol had the greatest effect on pronunciation,” she explains. “We joked… maybe drunk Germans just sound more like Dutch people.”

But a similar experiment carried out in the 1970s asked English speakers to perform a pronunciation test in Thai, a language they had no experience with. The results also underlined that one alcoholic drink can lead to better pronunciation of a second language.

Anxiety

While alcohol diminishes concentration, cognitive skills and motor skills, it simultaneously decreases inhibitions. And anxiety is often what leaves many people tongue-tied when they are trying to speak a foreign language.

“One possibility is that [our results] are due to the tension-reducing effects of alcohol,” says Fritz Renner, another co-author of the Maastricht study. “People might just be a bit more relaxed about speaking a foreign language and feel less anxious”.

Getty Images

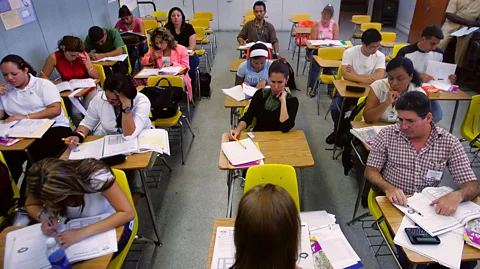

Getty ImagesAntje Rebecchi, a German-language lecturer at New York University Berlin, has taught foreign students in the German capital for fourteen years. She believes anxiety plays a decisive role.

“Anxiety is the biggest problem facing those learning foreign languages,” she says. “People do not want to lose control, make mistakes, and be embarrassed. It’s a question of insecurity. Many people think the strange sounds they produce in a foreign language make them sound silly. If you create a relaxed atmosphere in the classroom where you can laugh at yourself – through singing songs, playing games, or having fun – then language learning improves. And you can have this kind of fun without alcohol!”

So, alcohol reduces anxiety a little, but does it also make you braver? The Maastricht study looks at “Dutch Courage” after all. Renner says that, surprisingly, does little to increase confidence levels.

Before drinking, the group of students were asked to self-evaluate their confidence levels, and those who had drunk alcohol did not say they felt braver. They probably only felt less anxious.

Getty Images

Getty Images“We started with the idea that people only think they are getting better but actually they get worse,” says Renner. “In the end, we added a question mark behind ‘Dutch courage’ to the title of our study. The study is not showing that people get Dutch courage, it’s rather showing the opposite. Their self-perception is not affected by alcohol consumption.”

In other words? Language performance improved, probably due to a reduction of anxiety levels – but confidence levels, strangely enough, did not increase.

Not a performance enhancer

The authors of the Dutch study are quick to say, however, that alcohol should not be regarded as a performance enhancer. It is something Jonathan Howland, professor of emergency medicine at Boston University Medical Center, who has authored dozens of studies on alcohol in the workplace, agrees with.

Howland’s research has looked at the effect of intoxication on performance. One study looked at how maritime cadets simulated the piloting of a merchant ship while under the influence of alcohol. Howland associates the term “Dutch courage” with fooling oneself.

“In our studies on maritime cadets, two things happened,” he says. “One was they did a lot worse when drinking than under placebo condition. And number two, those who received alcohol actually thought they were doing better than they were. That’s the ‘Dutch courage’ thing. ‘Dutch courage’ means, in my mind anyway, that the alcohol makes you feel that you are doing better than you are.”

Renner, from the Maastricht study, meanwhile does not want too much to be made of the study’s connection between alcohol and performance. “We don’t want to downplay the established negative effects of alcohol consumption,” he says. “They definitely outweigh any potential positive short-term effects that we find under controlled lab conditions. The message is not that alcohol is a performance enhancer for a language. It’s much better to study harder, to go out there and speak to locals in a bar – with or without alcohol.”

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, please head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

{"image":{"pid":""}}

Battlefield linguistics

Dutch courage is an expression originating from the Anglo-Dutch wars of the 17th Century relating to alcohol’s effect in improving confidence levels. British soldiers fortified themselves with the local spirit – jenever, or gin – when going into battle against their Low Country enemies. Not only did gin make them feel braver, but it created the illusion of warmth during winter battles.