Keeping the lights on in Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan

Ali Al-Saadi/Getty Images

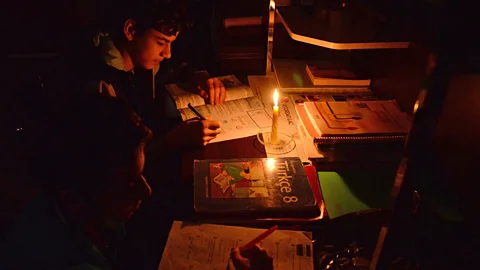

Ali Al-Saadi/Getty ImagesIt’s hard enough to start a business. Now imagine trying to get a start-up off the ground with slow and unreliable internet access, daily electricity cuts, a byzantine system of approvals and even border-crossing security concerns.

This is the harsh reality for many people in the Middle East, where reliable 24-hour electricity and efficient online payment systems still aren’t readily available.

Even a trip upstairs in a lift begs the usual question, “Fi Kahraba? [Is there electricity?],” said Nina El Hajj, who now works at a bank in Beirut, Lebanon, but spent seven years living and working in Canada.

Those who return to the region to start businesses after completing higher education in Europe and the US are frustrated by the slow pace of change in their home states.

“It’s a miracle that things get done,” said El Hajj. “If something is late, people are usually understanding because of the slow internet and power cuts,” that can last at least three hours a day within the city, or longer further out.

Lebanon, for instance, has been making do without round-the-clock power since the end of its civil war in 1990, causing most businesses to rely on expensive, noisy generators for at least three hours per day.

Still, there is hope infrastructure will improve, and thus the prospects for entrepreneurs and businesses.

“I don’t think this can be ignored much longer,” said Jad Chaaban, assistant professor of economics at the American University of Beirut, estimating that regular access to high-speed internet could boost gross domestic product by at least 2%. “It’s just a matter of time that people will rise up for economic reasons.”

A new breed

Surviving in such a challenging business environment has toughened and galvanized a new breed of entrepreneur.

“We’re having to redefine how we do business,” said Fadi Daou, founder and chief executive of MultiLane, a global hardware exporter based in Lebanon. Daou started his company in 2006, after founding several information technology firms in the US. He said that while Lebanon continues to have a strong pool of talent for research and development, there are still significant challenges

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA further frustration is the disparity between different countries in the region; while some struggle to keep the lights on, others have slashed red tape to attract foreign business.

“We recently opened a branch offshore in Dubai. It took me one hour to sign the documents,” he said, compared with Lebanon, where it’s still a “tremendous effort.”

Faced with high import and export fees at home, Daou now outsources most of his industrial production and expansion to the US, Taiwan and China, and keeps only a small team of around 20 hardware designers in Lebanon.

In Iraq, similar challenges are compounded by ongoing security concerns, particularly when it comes to moving goods over the border.

Azzam Alwash, who invests in Iraqi real estate for clients abroad, said that importing household and construction goods such as air-conditioners and marble into Iraq has become more difficult because authorities in ISIS-controlled areas demand bribes from truck drivers carrying cargo. To avoid this, Alwash no longer brings materials through Jordan, but instead sends them through Turkey by plane to Iraq. The added cost is then, unfortunately, passed on to the consumer, he said.

Tricky delivery

Even doing business in more stable countries such as Jordan can pose unique challenges. Eddy Farhat, chief strategy officer for the Amman-based online clothing retailer MarkaVIP, said few people, for instance, use street addresses for deliveries. “You’d be surprised that in Saudi Arabia they have addresses, but nobody uses them,” he said. “If they [live] next to a pizza restaurant, they’ll reference that. When people are entering a shipping address at check-out, it’s not an address I can put on Google maps and find.”

In addition, the company’s cash-on-delivery system — a popular feature for customers who are uncomfortable using credit cards — has taken a toll.

Ilyas Akengin/AFP/Getty Images

Ilyas Akengin/AFP/Getty Images“Today, any e-commerce business [elsewhere in the world] gets money from customers before getting products from suppliers… For us, it’s a completely different beast,” he explained. “When we bring items to customers, they can say no. This affects business by 20%. This causes problems on the balance sheets. We only buy products that our customers order… The ‘cash’ is stuck in the warehouse in form of returned products.”

No credit

A lack of bank financing is another major hurdle. That means that some business owners, such as Moutaz Al-Khayyat, try to run their firms within the confines of an operating budget. After fleeing Syria in 2011, Al-Khayyat re-established his contracting business, UrbaCon Trading and Contracting, in Qatar, where he is now a citizen. He employees 12,000 staff at the head office in Doha and at branches in Egypt, Jordan and Morocco.

Al-Khayyat said banks impose strict rules on the guarantees needed to finance contractors competing for large projects which are “a stumbling block to the implementation of these projects,” he said.

Construction companies also face different standards when they bid on projects in different countries throughout the Gulf region, he said. They face “fierce competition” from foreign companies that get “80% of the infrastructure and construction projects” in the Gulf Cooperation Council, the regional political and economic union, he said.

Why stay?

Still, entrepreneurs like Alwash are determined to succeed. “I’m from this area,” he said. “I can’t give up on Iraq. Giving up on Iraq is like giving up on a dream … There’s huge potential here. A more rational person would have given up a long time ago. But I’m an emotional investor — the worst kind.”

Daou is just as committed to Lebanon. “We have unique products that are developed by engineers in Lebanon,” he said, adding proudly, “They say made in Lebanon.”