Inside Italy's secret mosaic school

Alamy

AlamyHidden in a quiet Italian town is one of the world's most unique art schools – and a rewarding destination for curious travellers.

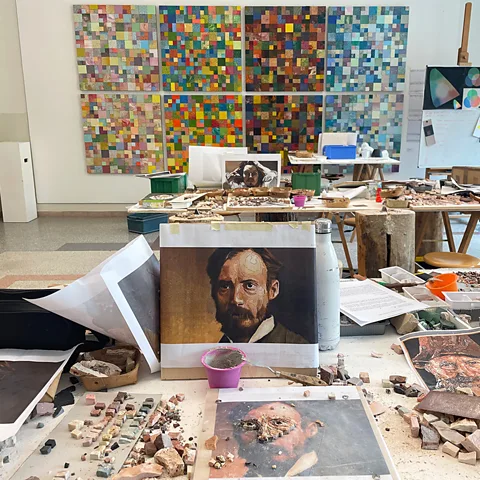

Walking the corridors of the Scuola dei Mosaicisti del Friuli (Friuli Mosaicists School) on a Friday morning, the first thing I noticed was the silence. I had expected the chatter of students, the hum of conversation between teachers, the shuffle of footsteps. Instead, the air was still, broken only by the occasional tap of a hammer and the delicate click of tiles sliding against tiles.

The second thing was the mosaics – everywhere. In the entrance courtyard, where a full-scale tessellated version of Picasso's Guernica greets visitors. In the hallways, where tiled reproductions of artworks like Michelangelo's Pietà and the Virgin and Child from Istanbul's Hagia Sophia line the walls. Mosaics climbed across flat surfaces and curled around corners, turning the entire building into a living archive of pattern, precision and patience.

Those same qualities were on full display inside the classrooms where students sat bent over their workstations, eyes locked on the fragments beneath their fingers. Mosaic, I would learn over the course of my visit, demands this kind of concentration: a craft shaped not just by hand and material, but by a collected atmosphere where meticulousness can thrive.

The school has been nurturing this kind of dedication for more than a century. Founded in 1922 in Spilimbergo, a small town of medieval lanes, a stately castle and Renaissance palazzi in Italy's north-eastern Friuli-Venezia Giulia region, it was originally created to provide formal training to local artisans and preserve the area's ancient mosaic tradition — one that dates to the Roman Empire and has left its mark on everything from Byzantine basilicas to modern monuments.

Marianna Cerini

Marianna CeriniToday it's the only academic institution in the world entirely devoted to the mosaic arts. Students of all ages, from high school graduates to mid-career creatives, come from across the globe to enrol in its rigorous three-year programme, during which they learn historical mosaic techniques – from intricate Greco-Roman patterns to luminous Byzantine compositions — before experimenting with more contemporary, freeform designs.

In recent years, the school has also become a destination in its own right, drawing design-loving travellers intrigued by the singular world of mosaics to explore its grounds on both public and private tours. Some 40,000 visitors do so annually, making the Scuola Mosaicisti one of the most visited sites in Friuli.

Plan your trip:

How to visit: The school is open year-round and welcomes both guided and independent visitors. Entry costs €3. Daily tours (including weekends) can be booked via the Spilimbergo Tourist Office.

Want to learn?: Short mosaic courses (four-days to a week) run throughout the year. Designed for beginners, they offer a rare hands-on experience. A minimum of five participants is required. More info here.

Where to stay: Try Relais La Torre, a charming B&B in Splimbergo's old town. The three-star Hotel Consul is another central option, with nine rooms and studios plus a restaurant serving traditional Friulian fare.

How to get there: Spilimbergo doesn't have a train station. Rent a car from Venice or Trieste – each just around an hour away.

While around 40 students are admitted to the three-year programme each year, no more than 15 complete the full curriculum, earning the title of maestri mosaicisti (mosaic masters). Of those, only a select group of six go on to do a fourth year – a sort of master's degree – to further sharpen their skills.

"It takes a lot of hard work and discipline to become a maestro mosaicista," said Gian Piero Brovedani, the school's director. "This is an art that's both humbling and exacting. It teaches you to slow down, pay attention and find beauty in repetition."

Marianna Cerini

Marianna CeriniIndeed, mosaic-making is an incredibly precise specialty. It requires the artist to painstakingly place together hundreds, sometimes thousands, of small pieces called tesserae (which can measure as little as 0.5cm) to form intricate patterns and lifelike scenes. Made from marble, glass, smalto (opaque glass tiles) and even shells, these tiny inlays demand thorough craftsmanship and an intuitive sense of rhythm and placement.

As Brovedani noted, it's also deeply collaborative. Mosaicists generally work solo on sections of large compositions, but the true effect of that work emerges only when viewed in unison. "It's a craft that asks you to 'erase' yourself, in a way," said third-year teacher Cristina de Leoni. "One tile on its own doesn't say very much, but together with others, it creates an artwork. There's no ego in mosaic-making."

Glancing at the craft's rich history – which dates to Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BCE and stretches across countries and cultures, from the Greeks to the Maya, the Byzantine Empire to the Islamic world – it's easy to see her point. There are no Giottos or Raphaels in the mosaic arts, no singular Mona Lisa. Instead, this expressive form has always relied on anonymous virtuosity, walking a fine line between art and artisanship.

That's been all the truer in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, where mosaicists never stopped honing the craft, even as it slipped from the spotlight from the Renaissance onwards. With its abundance of stones from the Tagliamento (Friuli's main river) and close cultural ties to Venice – a city long at the epicentre of European art and craftsmanship – the region quietly became a stronghold of mosaic tradition, its skilled artists sought after across continents. In the 19th Century, Friulian artist Gian Domenico Facchina even helped usher mosaics into the modern era, devising the rovescio su carta (reverse on paper) method to assemble panels off-site – a game-changer for scale and speed. The foyer of Paris' Opéra Garnier was the first to showcase it.

Marianna Cerini

Marianna CeriniSince then, Friulan mosaicists – most trained in Spilimbergo – have made their mark worldwide: from Rome's iconic Foro Italico sports complex to the New York City subway station at the World Trade Center; from the dome of Jerusalem's Church of the Holy Sepulchre to Tokyo galleries. These works are proof of a tradition that continues to evolve, tessera by tessera.

"The duality of mosaics makes them endlessly fascinating," said Purnima Allinger, a third-year student who left a marketing career in Berlin to pursue mosaics. "It's a precise and meditative-like craft, but also expressive and emotional like art. You're always shifting between the two – it keeps you completely engaged."

Amos Carcano, a maestro mosaicista from Switzerland, agrees. "You work with your hands, but you're also constantly inventing, playing with texture, colour and patterns. Contemporary mosaics push those boundaries even further. It's a tradition, but it's also wide open."

Carcano is currently one of 10 alumni working on one of the school's most ambitious pieces yet: a 1,265-sq-m mosaic floor for the courtyard depicting Friuli's native flora and fauna – a project set to take more than a year.

It's not just maestri who create for the school. All those mosaics I saw as I toured the premises? They are by past and present students. "We think of the school as a bottega – a workshop," says Danila Venuto, who teaches mosaic history. "And in a workshop, you learn by doing. It's only natural that the students are put to work as soon as they start learning the ABC of mosaic. This is a craft that's mastered and kept alive through making."

Marianna Cerini

Marianna CeriniAnd increasingly, you can learn even as a visitor. The school offers corsi brevi – short courses ranging from four-day intensives to week-long programmes – to give travellers a hands-on introduction to the art. Meanwhile, the tours include access to an archive of more than 800 mosaic works and the opportunity to glimpse into the classrooms where students and maestri work side by side. Leading each visit is usually one of the 79 guides that have specifically been trained by the school, or, for a more local flavour, Spilimbergo's volunteer city guides, who often pair the experience with a stroll through the town.

The experience doesn't stop at the school gates. Spilimbergo itself is full of mosaics: decorating the interiors of its imposing Roman-Gothic Duomo, embedded in shopfronts, woven into restaurant floors and tucked into hidden corners of the old town. On its main thoroughfare, Corso Roma, mosaic shops and showrooms display beautiful creations from the school's alumni for purchase; while on the outskirts of town, Fabbrica di Mosaici Mario Donà, a historic family-run kiln that moved from Murano to Spilimbergo in 1991, can be visited by appointment to see where the enamels for the mosaics are made.

Travel just a little further and you'll reach the source material that has long shaped the school's practice: the grave – smooth, river-washed stones carried by the Tagliamento. Nearby lies the Magredi, a stark plain formed by gravel brought in by two local streams, the Cellina and the Meduna. Though it may look barren, it teems with a variety of flora and fauna, from wildflowers to birds of prey – the very subjects featured in countless Friulian mosaics, including the school's soon-to-be-completed outdoor floor.

"People from Spilimbergo – and from Friuli at large – are very proud of this centuries-old tradition," said Venuto. "Mosaic-making is part of our cultural DNA, a true Friulian legacy."

And in this corner of Friuli, if you're curious, you're welcome to be part of it.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.