How Japan’s tsunami-ravaged coastline is being transformed by hope

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIwate and Fukushima Prefectures were ravaged by the 2011 tsunami that precipitated a catastrophic nuclear disaster. Now, this tragic, beguiling region is welcoming travellers back.

Hope spiralled tender as a rice shoot along the resurrected Sanriku Railway Rias Line in north-eastern Honshu. Summer's blooms spilled from pots on station platforms; storybook houses peeped from the forests' folds; a man knelt beside the ice-blue river and cleansed a fistful of spring onions. Rice crops flashing by in the valleys were ripe for the harvest: their imperial yellow shimmer filled the windows as my friend and I rattled along this once-moribund coastline.

On 11 March 2011, communities along the north-eastern seaboard of Japan's biggest island, Honshu, were swept from their moorings when an earthquake measuring 9.1 on the Richter scale precipitated a tsunami of monumental proportion. Seawater barrelled into the saw-toothed shoreline, upturning infrastructure, buckling forests, flushing lives from every crevice. When the oily tide receded, little but splintered flotsam remained.

Such devastation is familiar to this country located atop a fault-line; the archipelago nation has endured too many natural disasters to remember – most recently, in January 2024, a 7.6 magnitude earthquake in the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture. But remembrance is the ritual whereby the Japanese make sense of their fate. In Honshu, a purpose-drawn map demarcates the numerous "disaster memorial facilities" strung out along the 500km stretch of coastline affected by The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011. Obscured from view below the railway line are cairns erected by earlier generations to warn of nature's ferocity.

"Don't build homes below this point," reads one inscription. "No matter how many years have passed, be alert for tsunami."

That volatile ocean was a sea of tranquillity as we rambled northwards from the city of Kamaishi to Namiitakaigan, a seaside hamlet four hours north of Sendai in Iwate Prefecture. Here, flowers trailed from the cottage gardens abutting Namiitakaigan Station; a cenotaph 266m uphill from the beach was looped with Japanese script: "This is where the tsunami reached."

Getty Images

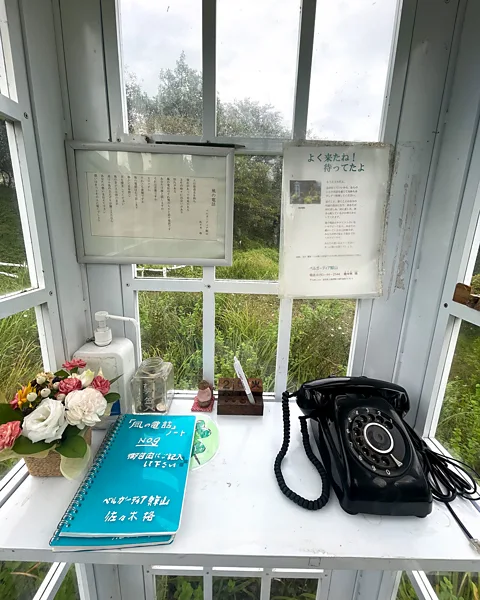

Getty ImagesWe'd been drawn here by a story: in a beautiful garden on a nearby hill stands a phone box where people commune with the dead. Before the disaster, Namiitakaigan resident Itaru Sasaki created a metaphorical connection with his recently deceased cousin by placing a disconnected telephone inside a British-style phone box. Here, he explained in a 2016 episode of This American Life, he could speak to his cousin, his thoughts "carried on the wind". As stories of Sasaki's ritual spread, those affected by the tsunami – and other tragedies – arrived to seek their own solace on "The Phone of the Wind".

RAIL JOURNEYS

Rail Journeys is a BBC Travel series that celebrates the world's most interesting train rides and inspires readers to travel overland.

Though thousands of people have trod the path to Sasaki's garden, we were its sole visitors that day. Birds flitted between frothy crepe myrtles and maple leaves slowly changing colour; it was a poignant setting in which to meditate on loss: so electric with life, so hefted with sorrow. I closed the phone box door behind me, lifted the receiver and silently communed with the loved ones I'd lost.

The mood lifted on the way back into town: we met a woman pushing a pastry cart from door to door, and bought two of her custard-filled doughnuts.

"Oishi! (Delicious!)" we said, skipping down the hill.

Second-hand memory assailed us once more on the road leading to Minshuku Takamasu, our lodging for the night: "Tsunami Inundation Section," a sign said. But proprietor Yasuko Nakamura's face was wreathed with a smile as she welcomed us in. Only the roof of her elevated ryokan was damaged by the tsunami, she communicated through gestures and a translation app and my friend's rusty Japanese.

“I was at my home in Trono [an hour’s drive inland] when it came,” she said.

Catherine Marshall

Catherine MarshallAnd though foreign guests are now rare, Nakamura was busy enough with her long-term lodgers: high school boarders, a fisherman-diver who made his living from the bay, a builder working on the reconstruction of the nearby town of Otsuchi, which we'd passed through on our way here. Half of its dwellings and most of its commercial properties were wiped out by the tsunami. The builder's efforts would help to make Otsuchi stronger, he said, as Nakamura served the fruits of that once-vengeful sea for dinner: wakame (seaweed) salad, grilled saba (mackerel), miso broth bobbing with a delectable but indeterminate ingredient.

"What is it?" I typed into her app.

"It’s made by kneading fish," she explained, her Japanese script blooming as graceful as the kaiseki bowls she'd laid before us.

How to get here

Japan Rail's JR East Pass goes from Tokyo to Kamaishi on the Tohoku Shinkansen and JR East Line. From Kamaishi, take the privately owned Sanriku Railway Rias Line to Namiitakaigan (tickets are available at the station). The line continues south along the coast from Namiitakaigan to Ofunato, where the BRT transfers passengers to Rikuzentakata and Kesennuma. From here, use your JR East Pass to travel to Sendai on the Kesen-Numa Line and onwards to Futaba and Iwaki on the JR Joban Line.

The fisherman-diver, we learned, owned an apple orchard in his home prefecture, Aomori. It snowed a lot there, he said, climbing out from an imaginary drift. Mercifully he wasn't diving off Namiitakaigan when the tsunami swelled forth. We shuddered collectively at the thought: there was no need to translate such imagined terror.

Next morning, we accepted a parting gift from Nakamura: delicately painted jars filled with sake.

"Famous sake, from Kamaishi," she said.

From Namiitakaigan, the train rumbled south along a coastline lapped by gentle waves. It was impossible to reconcile this scene with the images of 2011, when railway tunnels flooded, girders buckled and Koishihama Station was washed clean away. Now, scallop shell wreaths overflowed from an alcove on the station's reconstructed platform; a group of pre-schoolers alighted here with their teachers and affixed their own shell-adorned pennant to the shrine.

"A prayer," said a woman on the train who had intuited the question in our eyes.

Catherine Marshall

Catherine MarshallBut elementary tributes soon transformed into elegant homages. At our next stop, Rikuzentakata, the Hiroshi Naito-designed Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum plugged the shoreline like a brilliant white tombstone. The sky danced on the pool of reflection through an aperture in the portico ceiling; in the wings leading off it, we heard survivor testimonies, watched multimedia displays, pondered objects recovered from the deluge: a crumpled fire truck, a child's mud-spattered keyboard, a bus stop folded like origami. Remembrance gave way to deep reflection in the exhibits addressing bureaucratic shortcomings, outlining mitigation strategies for future disasters, expressing gratitude for the world's outpourings of assistance and sorrow.

"It is wisdom passed down to future generations," said guide Satoko Kinno.

We had a bus to catch, but Kinno urged us to climb the seawall overlooking the fledging forest fringing the bay – a replacement for the centuries-old pine plantation that once girded the city against the ocean's vagaries. The Miracle Lone Pine Tree was the plantation's sole survivor. But lethally poisoned by saltwater, it died in 2012; was it finished off by grief, I wondered? Now preserved with chemicals and supported by a steel rod, this monument loomed above the flattened landscape, a powerful symbol of resilience. Nearby, the tsunami-dashed ruins of Rikuzentakata Youth Hostel slumped over a pond as though mourning their own reflection.

From the seawall we looked back at the museum, which from this angle appeared to have been sliced from the bedrock. The masterpiece was enfolded in the tidy green skirts of Takata Matsubara Tsunami Reconstruction Memorial Park.

Beyond it, Rikuzentakata arose anew from the slurry.

The railway line south of the city - dismantled, too, by that wall of seawater - was still awaiting repairs. We caught the replacement Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) to Kesennuma, and the train onwards to Sendai. Here we boarded an empty carriage on the JR Joban Line bound south for Fukushima Prefecture. Until a few hours earlier, we had no idea where we'd be staying that night. Hotels were sparse along this route, the coastline it traversed still burdened by fallout from the tsunami-triggered nuclear disaster.

Catherine Marshall

Catherine MarshallDarkness had fallen by the time we arrived at Haranomachi Station. Not a soul roamed the streets. The lacquered facade of a ramen bar glowed red, but no one stirred inside. We bought sandwiches from a 7-Eleven and retreated to our room at Hotel Areaone Minamisoma, which seemed bereft of other guests.

As though summoned by us, a shuttle bus was waiting outside the station the next morning at Futaba, located close to the site of the nuclear accident. Radiation levels here are said to have returned to normal. Bright murals flowed across the huddle of buildings still standing in a part of town recast as "Futaba Art District". Acres of wasteland spooled by as the bus driver steered us towards The Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum. There it stood amid a sea of empty lots: a pale edifice of Cubist proportions – a white elephant, perhaps?

But to our surprise it was brimming with visitors, mostly high school students on excursions. I observed them absorbing, wide-eyed, events they were too young to remember. Then I stared for a long time at a model inspired by the Fukushima Innovation Coast Framework, an initiave aimed at re-establishing an industrial base in this decimated region; it depicted Futaba rebuilt as a "city of the future": lush farmland, vibrant streets, a beach filled with holidaying families.

"It's growing step by step," said guide Kenichiro Hiramoto. "Only 70 or 80 [residents have returned] to Futaba Town, but they try to organise their community. Now the trend is newcomers, young people – and, of course, the municipality supports them."

We will visit this city of the future 20 years hence, pledged my friend and I on the train to Iwaki, two-and-a-half hours south of Futaba. Though badly damaged by the tsunami, the city has rebounded. After dinner that night we descended into a basement bar, Burrows, just as it was closing. Owner Kazuya Hanazawa agreed to mix two last cocktails. Shaking, stirring, cutting wedges of lime, he lamented the hundreds of Iwaki residents lost to the tsunami. He spent six months afterwards helping mop up, and made his bartop from wood salvaged from the wreckage.

"Japanese are very tough," he said, pressing his fist to his heart. "I wanted to create a place where people could feel good. It's a small [start], but people from all over – Okinawa, Hokkaido, all of Japan – are coming back to Iwaki."

Hanazawa placed our cocktails before us: vodka concoctions fizzing like daylight in the gloom.

"Kanpai (Cheers)," we three said.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.