Rocky Bucano on the NYC landmarks that birthed hip-hop

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty ImagesFrom 1520 Sedgwick Avenue to Haffen Park, the pioneering DJ and founder of the Universal Hip Hop Museum shares where to go to see hip-hop's roots.

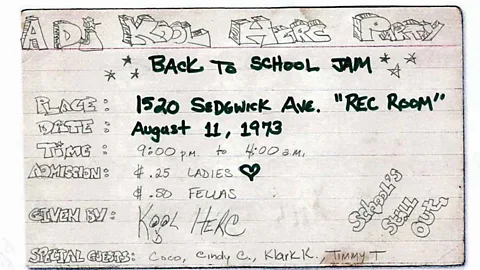

On 11 August 1973, more than 300 New York City teenagers flocked to the West Bronx, packing the rec room of the apartment building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue for what was billed – on handwritten index cards – as "A DJ Kool Herc Party – Back to School Jam". As the crowd poured in, Kool Herc (real name: Clive Campbell) took to his turntables to incite a sonic and cultural movement that had been brewing for decades.

The 18-year-old masterfully stacked identical copies of a single record atop the surfaces of his twin turntables, isolating a syncopated drumming rhythm, a breakbeat named for its ability to grant party-goers an extended dance break. Thus, 50 years ago, by the hand of Kool Herc, hip-hop was born.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile hip-hop has since become a global phenomenon, no other place is as intrinsically tied to the sound, culture and legacy of hip-hop as the city that inspired it – and Rocky Bucano is determined to remind the world of hip-hop's New York roots.

Bucano was a 14-year-old kid in the Bronx when Kool Herc birthed hip-hop, but was instantly hooked. After getting his first turntable, he started spinning under the name Kool DJ Rock and went on to become one of New York's most in-demand party promoters, putting on events that helped launch hip-hop legends like Grandmaster Flash. These days, Bucano is the executive director and founder of the Universal Hip Hop Museum, which he created alongside hip-hop luminaries like Kurtis Blow, Ice T, LL Cool J and Nas to serve as "the official record of hip hop". The museum is currently located in the Bronx Terminal Market, but construction is underway for a new 52,000sq ft space in the South Bronx that will open in early 2025.

Bucano recently shared how the culture of New York City in the 1970s inspired this sound, how hip-hop spread and the New York landmarks where visitors can see where one of the 20th Century's biggest cultural movements took root.

WENN Rights Ltd/Alamy

WENN Rights Ltd/AlamyRocky Bucano's hip-hop hotspots

What do you think it was about New York City that inspired hip-hop?

Hip-hop was started by teenagers – Black and brown teenagers from the South Bronx and other parts of the Bronx. Those teenagers were at the forefront of creating something new by going outside and bringing turntables, microphones and speakers [and] plugging them into the lamp poles to get power because there were no generators back then. And I think a lot of that creativity has to do with their environment.

I would say we were all in high school, and there were no [auxiliary] programmes in the high schools. So, in order for us to express our creativity, some of us took to DJ-ing, some of us took to dance, some of us took to poetry and some of us took to writing on walls in trains – graffiti. And that was really the way for everyone to express themselves. These kids would go out into the world and use their ingenuity to create outdoor block party experiences, and folks from all over would come to these block parties to hear kids playing different music that would not normally be played on the radios. So, this inspired people to come together as a community.

What do you remember about the atmosphere of New York City in the early 1970s when hip-hop first began, especially in the Bronx?

New York City was going through very desperate economic times. Landlords were burning down buildings in the South Bronx to collect insurance money. The city was trying to stave off economic collapse and financial ruin. There was poverty and violence all around, not just in the Bronx. The kids were really trying to escape from all the negative stuff surrounding them and just find peace, because peaceful times bring people together.

Emily Marie Wilson/Alamy

Emily Marie Wilson/AlamyWho were some of the people at the forefront of this movement?

Each neighbourhood really had their own "king" – that was the permanent DJ in that neighbourhood. So, you had Kool Herc, but you also had Grandmaster Flash and you had myself. I started as a teenage DJ. You also had Breakout and Baron who were also from my part of the Bronx, the north-east section of the Bronx. And obviously you had Afrika Bambaataa, who was in another part of the Bronx, and Disco King Mario. So, every neighbourhood had its own unique way of hosting block parties.

What were the sounds and genres influencing hip-hop at the start?

The way they were playing it, they were using pretty much just bits and pieces of disco records that had what we would call "breakbeats". That also allowed the kids that had been listening to the music to create a new dance style called "breaking" [later called "breakdancing"]. Breakbeats were synonymous with the birth of hip-hop because they created that energy.

Randy Duchaine/Alamy

Randy Duchaine/AlamyHow did these teenagers get hip-hop from the parks to venues?

The nightclub scene. Disco Fever was a small nightclub that allowed the teenagers to come in and party. Most of the discos didn't allow teenagers. They wanted young adults that wore shoes and dressed nicely. They didn't want the sneaker crowd. But [future music executive] Sal Abbatiello understood that there was something happening in the streets, and he wanted to leverage what was happening in the streets and bring it into his club called Disco Fever. And he gave Grandmaster Flash [a chance], I think [on] a Tuesday night, just to see how it would go. They saw that Grandmaster Flash could bring in all of these people from all over, and now there was a line to get into the nightclub. So, they kept it going. Disco Fever gave a lot of rappers their first break – Run DMC, Kurtis Blow, The Sugar Hill Gang.

From there, the nightclub scene in New York City was more about big hotel ballrooms and restaurants that would be converted into nightclubs. A lot of the Black and Hispanic people who wanted to party couldn't get into those clubs like Studio 54 and Xenon's – they didn't have that kind of access. So, (the now-closed) Superstar Cafeteria, Frank's, The Cork & Bottle – all of those places – were restaurants that the promoters would rent and then convert into nightclubs after hours. The restaurant would close around 18:00-19:00, and then the promoters will come in around 19:00 and open up the doors at 21:00, and it would be a club.

At the museum, you've highlighted a few places around New York City people should visit to pay homage to rappers who have helped popularise the genre: the new Notorious BIG statue in Brooklyn, the A Tribe Called Quest mural in Queens and the Big Pun mural in the Bronx. What are some other places you'd recommend hip-hop fans visit around the city to see where this sound started?

The definitive places, I would say, are the Bronx River Community Center because that's where the Zulu Nation held so many of their performances. 1520 Sedgewick Avenue obviously is one. Haffen Park is another one up in the north-east section of the Bronx. That's where [filmmaker] Charlie Ahearn brought everybody together to talk about the [world's first hip-hop] film, Wild Style, that he would later produce. That's where they figured out who would be in the movie, and that's where I used to be a top DJ.

Al Pereira/Getty Images

Al Pereira/Getty ImagesFrom DJ-ing to running a record label to heading up the museum, what have been some of the highlights of your career?

Just being able to work with the producers I've worked with. I've been fortunate to work with all different types of producers from Teddy Riley to LA Reid, Babyface and Dallas Austin. And I've nurtured some producers that came out of my own record label, Strong City Records, that I started during the golden era of hip-hop in 1986. So, DJ Jazzy Jay, who worked with A Tribe Called Quest; Diamond D, who went on to produce the Fugees, they both came out of the offices of Strong City Records.

And then being able to work with so many different artists. [Grand Puba] Maxwell, who was a part of Masters of Ceremony, that later became Brand Nubian. Working with Fat Joe early in his career. Just being able to have a lot of different relationships with different people.

But the biggest milestone for me is what I'm doing now with the Universal Hip Hop Museum. I'd call this a hip-hop project, because the museum is dedicated to making sure that the history is preserved, protected, documented and properly celebrated. To me, this is so much more important and so much bigger than anything else that I've ever done in my previous career.

Universal Hip-Hop Museum

Universal Hip-Hop MuseumWhat do you have planned for the 50th anniversary of hip-hop?

We have a great block party on 11 August at Mill Pond Park. Chuck D is performing, The Fearless Four, MC Sha Rock… we have about 20 or 30 different acts that are going to perform.

We've also partnered with Red Bull, and they are hosting a special preliminary for their BC One World Final in New York City where they'll be doing a special tribute to breakdancing, and that's 12:00 to 18:00. And then after that everyone is going to be running to Yankee Stadium for the Hip-Hop 50 Concert featuring Run DMC, Snoop Dog and Lil Wayne, Ice Cube, Remy Ma, Fat Joe, Common, TI and Wiz Khalifa. So that's going to be a great concert.

And on 24 August, we're going to have our inaugural benefit gala at Cipriani's [on] 25 Broadway. We have been hosted by Yo-Yo and Ari Melber, and we have De La Soul performing.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.