Orris: The world’s rarest perfume ingredient

Kokophotos/Alamy

Kokophotos/AlamyA scent with few natural analogues, orris is exceedingly rare; the fact that people continue to seek out this fragrance despite its high cost speaks to its enduring appeal.

imageBROKER/Alamy

imageBROKER/AlamyAncient Greeks and Romans bottled it as essential oil. Innkeepers scented their linens with it centuries ago. Today, orris can be found throughout the world: as a flavour in tinctures, medicinal syrups and spice mixes; as a base note for aromatic spirits and cosmetics; as an iconic fragrance in perfumes and potpourris. And it can cost more than gold.

Shades of raspberry, violet and pepper make up this rare scent, which is distilled from the root of the iris – not the slender ‘Siberian’ iris typically found in florist shops, but the ‘bearded’ iris, the type famously painted by Vincent van Gogh. These flowers grow widely in Tuscany, where they are cultivated and sold in shops as giaggiolo, from the Italian for iris flower.

Elisabetta Abrami

Elisabetta AbramiThe history of this rare essence begins where it was first harvested: the Italian countryside. Just beyond the tiny village of San Polo (about a 30-minute drive from Florence) sits the Pruneti Farm. Surrounded by steep hillsides purpled by blossoms, the mill has been operational for nearly two centuries. Today, brothers Paolo and Gionni Pruneti are dedicated to preserving the traditional methods of orris extraction, a costly, labour-intensive process passed down from generation to generation.

Aside from extra virgin olive oil, the Pruneti farm is renowned for orris, even in a farming town famous for its iris products. Each spring, Italy’s Chianti region turns shades of periwinkle and white as blooming irises dot the landscape. San Polo even holds an annual iris festival to celebrate the flower, which has for centuries featured prominently on the Florentine coat of arms.

The resin extracted from the roots of these flowers – orris butter – is exported all over the world for use in cosmetics, perfumes and powders, making production here a unique cottage industry, one that in many ways resists mechanisation.

imageBROKER/Alamy

imageBROKER/AlamyThe iris flourishes in May. Seeing all these hectares of farmland turn blue is really marvellous,” said Gionni.

imageBROKER/Alamy

imageBROKER/AlamyThe farm’s stony soil and temperate climate provide ideal growing conditions for the iris florentina, which flourishes in the warmth of the Mediterranean. But years must pass before orris can be bottled, powdered or made into perfume.

At Pruneti, iris roots are left underground for four years, while a variety of ‘grubbing operations’ take place: flowers in various cycles of growth are bedded, weeded, cut and harvested, allowing for year-round production of orris. Harvest takes place in the summer months, from June to September, when the flower’s rhizomes, or bulbs, are dug up from the earth with a two-pointed hoe. Odourless when first extracted, the bulbs are cleaned, hand-peeled with a curved blade and then either left to dry in the sun or readied for distillation. A small portion is left attached to the stem of the plant, which is then replanted.

These dried iris bulbs must be protected day and night against fungus and insect attack, which would destroy the producer’s valuable harvest. As they mature, the rhizomes develop a violet-like aroma, as well as natural fixative properties that can prolong other scents.

Elisabetta Abrami

Elisabetta AbramiNothing about the cultivation of orris at Pruneti is remotely industrial. Much of the work is done by hand, in small batches, with basic tools. That might account for the aromatic’s historical significance, and its current value as a precious commodity: high-quality orris can fetch more than 50,000 euros per kg, and it takes half a ton of orris root to produce a single kilo of essential oil.

Orris cultivation also requires a considerable workforce. For years at the Pruneti farm, that meant involving the entire family: adults tended the garden or hauled plants to farmhouses (with the help of donkeys), children peeled bulbs as they would potatoes, aunts and uncles drove tractors through the pasture or ground up the dried iris roots.

Today, the brothers make use of newer technologies, but continue to be guided by centuries-old production methods. They are particularly interested in early recipes that promote the flower’s herbal properties. Indeed, orris was first used as both a perfume ingredient and as a medicinal nostrum, sold in a medieval apothecary not far from where Pruneti farm now sits.

Alessandro0770/Alamy

Alessandro0770/AlamyWe spent so much time together, telling stories as we worked. Those three months side by side every day made us richer,” Gionni recalled.

Darryl Brooks/Alamy

Darryl Brooks/AlamyOfficina Profumo-Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella contains a storied history of aromatic riches. At the 400-year-old apothecary (some say it is the oldest still-operating pharmacy in the world), elaborately decorated rooms are filled with cabinets containing various tonics and jars of fragrant potions first brewed by an ancient order of monks.

The Dominicans, an order devoted to charity, devised herbal recipes here as early as the 13th Century, when poet Dante Alighieri was penning his illustrious Divine Comedy. Friars transformed the Santa Maria delle Vigne church into a monastery, and eventually a pharmacy, where they concocted medicinal remedies and perfumes, adding alcohol to the mixtures to keep scents from turning rancid. In fact, this enterprise’s manufacture of perfumes might be what attracted the patronage of its most famous customer: Catherine de’ Medici.

Fototeca Storica Nazionale/Getty

Fototeca Storica Nazionale/GettyWhen Catherine de’ Medici arrived in Paris, newly married to Henry, Duke of Orleans (and future King of France), she brought with her a trove of goods from her native Florence: various cooking utensils and techniques, powders and pomades, ballet slippers and high-heeled shoes, and a vast collection of herbs and spices. Her personal perfumer, René le Florentin, made the journey as well, and in 1612, de’ Medici commissioned a scent to commemorate her arrival: Acqua della Regina. Delicate, subtle and complex, ‘Water of the Queen’ was characterised by notes of citrus and bergamot.

The young queen’s sinister reputation – an interest in potions and occult arts, and even a penchant for murder – seems to have followed her through history (some blamed the death of her known enemy, Jeanne d’Albret, on a pair of poisoned gloves). Regardless, medieval Florentines were so taken with de’ Medici’s beauty regimes that concentrated perfumes (blossoms steeped in alcohol and fortified with musk or opopanax, a type of resin) quickly became fashionable throughout the city.

Artisans scented leather gloves with jasmine, violet, iris and orange blossom; noblemen hung sachets of potpourris and burned incense throughout the court. Preparations called vinaigres de toilette were wafted under royal noses to prevent a fainting spell or to ward off bad odours (of which there were many).

Elisabetta Abrami

Elisabetta AbramiCatherine de’ Medici might be considered the official sponsor of our pharmacy,” said Gianluca Foà, chief commercial officer of Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella.

Elisabetta Abrami

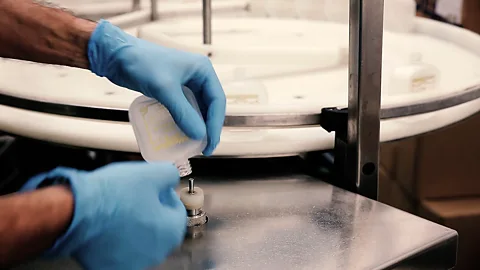

Elisabetta AbramiToday, Santa Maria Novella still sells traditional elixirs as well as more contemporary skin-care products and fragrances. Dried iris bulbs are transported from Chianti here in large casks, then pulverised into a powder and mixed with water and alcohol to extract an absolute, a stronger version of the plant’s essential oil. From distilled iris bulbs at long last comes orris butter: a waxy, yellow-coloured resin with an earthy sweetness that’s hard to replicate. This ingredient is used in countless products, including toothpaste, whitening powder, soap and perfume.

To that end, the pharmacy’s fixtures retain the spirit of the past: a simple apparatus used for distilling dried iris roots still sits beside old containers once used to hold ancient formulas and emulsions. Faded recipes line the walls, revealing that orris’ incomparable essence was once used as a treatment for various ailments, including bronchitis, liver disease and edema. Most remarkable, however, is that the provenance of its iconic botanical has not changed.

Of course, the factory relies on modern technology in order to meet consumers’ demands; over the years, Santa Maria Novella has expanded its operations across the globe, with locations in Paris, New York, Los Angeles, Tokyo and Paris. The factory can turn out 500 bars of soap a day in any one of 25 varieties (tobacco, almond and violet scents are popular), but each bar must be aged and hand-chiselled into its final shape.

Elisabetta Abrami

Elisabetta AbramiThe use of this ingredient makes the difference between artistic perfumery and industrial perfumery,” said Foà.

Florilegius/Getty

Florilegius/GettyOrris is a floral scent: versatile, tenacious and slightly feminine. Its incredible potency means that only a few drops of distilled orris absolute are needed, fanning the top notes of a perfume’s composition or flavouring botanical spirits like gin. But the language of smell, like the practice of perfumery itself, is often obscure. What, exactly, makes orris’ aroma so enchanting?

Perfumes are derived from countless natural materials – woods and mosses, resins and balsams, grasses and spices, flowers and animal by-products – many of which have been used for thousands of years. While perfumery is an ancient art, its aromatic qualities were not formally classified until the 20th Century; suddenly, a mysterious fragrance like orris could be described according to its key olfactory characteristics. Though these descriptions will only ever approximate the true scents they describe, perfume accords help us understand what distinguishes one note from another:

- Citrus: light, fresh bouquets such as orange, bergamot, neroli and tangerine

- Fougère: recalls damp green spaces and scented forests such as juniper, lavender or pine

- Aromatic: herbal notes that exude a piquant quality, like thyme, sage and rosemary, as well as tea leaves

- Floral: succulent aromas such as jasmine, tuberose, gardenia, phlox and honeysuckle

- Woody: variously austere or tarry in scent, these include cedar, fir, oud, palo santo, neem and vetiver

- Oriental: vanilla, patchouli, cinnamon and myrrh

- Amber: a golden resin derived from desert plants with warm, sweet notes

- Chypre: a leathery, lingering profile most commonly found in oak moss, as well as lichens, bamboo and buxus

With advances in extraction, more modern perfume variations have also emerged, such as ozone (a clean, androgynous smell), gourmand (scents with edible or dessert-like qualities) and green (vegetal, sharp scents). Changes in consumer taste have given rise to stranger varieties still, including brick, vinyl, lava, asphalt, rain, gunpowder and mushroom.

Throughout history, orris, however, has often played a role in fragrance, managing to enter compositions as wide-ranging as light eaux de cologne and as intoxicating as the white floral scent of a highly concentrated parfum.

Allstar Picture Library/Alamy

Allstar Picture Library/AlamyIn a world dominated by factory farming, chemical additives and synthetic ingredients, orris is exceptional: hand-harvested, painstakingly aged and nearly impossible to duplicate. Even trace amounts of this exquisite material allow for a wide range of applications, from perfume to beverages to medicine, making Florentine orris butter a much sought-after product.

The exotic bird of the floral world, orris still conjures images of nobility, of ancient traditions both secular and sacred: daubed on a royal wrist, splashed into a gin-gimlet, rubbed as an unguent on aching limbs or crushed into a fine powder that smells of violets, white flowers and the history of an entire region.

(Text by Adrienne Bernhard; video by Elisabetta Abrami)

The World’s Rarest is a BBC Travel series that introduces you to unparalleled treasures found in striking places all across the world.