Death row: The secret hunt for lethal drugs used in US executions

BBC

BBCWhen the supply of drugs used for lethal injections began to run out, a couple of prison guards in the US had to go out and find another source.

For over 20 years, Randy Workman was the man who walked people to their death.

As a senior corrections officer in the state of Oklahoma, he personally participated in 32 executions in various roles, including escorting prisoners, selecting executioners and sourcing lethal injection drugs.

"You could tell the moment they expired. You watch enough of them, you can just tell immediately they were gone," he told the BBC.

But his job took an unexpected turn in 2010, when Hospira, the maker of the drug sodium thiopental, stopped production in the US due to an unspecified issue with obtaining raw materials.

The drug, which renders a person unconscious and suppresses the nervous system, was one of three drugs in a cocktail widely used in executions, and the oldest drug to be approved for capital punishment.

The company tried to move production to Italy in 2011, where capital punishment is illegal, but the country refused to allow it unless Hospira could guarantee it wouldn't be used in executions.

So it became Mr Workman's job to find the drug from alternative sources.

It wasn't easy.

"You felt isolated because you felt like the world was mad at you," he said.

"It made you feel like you're doing something wrong. If you believe in the death penalty, we're really not."

At one point, Mr Workman was able to make connections with a drug company in India that looked like it would be able to deliver a supply unimpeded, but he abandoned the idea when he found the company didn't have the approval process used in the US.

It meant he couldn't guarantee what the drugs would do, if used.

"That was a scary thought. You don't really know what you're getting into and really can't take chances on the process," he said.

In the state of Arizona, prison boss Carson McWilliams was also on the search for lethal dugs.

He had been calling around US based pharmaceutical companies asking if they had any drugs left over from previous shipments.

"I probably contacted every drug company there was that I knew of. Most of them wouldn't even talk to me."

When none did, he too turned to the India supplier. In his case, he did order a few shipments, as did the Texas Correctional Department.

It was vital to procure the drugs, Mr McWilliams said, because in Arizona when a warrant for execution is issued, a penitentiary has 31 days to fulfil it before the warrant expired, at which point they would have to start the process again.

"That clock starts ticking. You're under the gun to make it happen. So you have to be creative and do what you got to do to make it happen," he said.

But when the drugs arrived in the US, federal officials confiscated them, putting Mr McWilliams back at square one.

'A secret and important mission'

That's when he made a connection with a pharmacist in England who could supply sodium thiopental. At that time, supply of the chemical was legal.

"It felt good because we know what these drugs are and we've used them before. And so we feel really confident that these drugs are fine," he said.

But the supplier wasn't a big drug company. In fact, Medhi Alawi operated out of an address which apparently also operated as a driving school in Acton, London.

Hundreds of vials of white powder had been parcelled into a cardboard box and sent off to Carson McWilliam's office in Florence, Arizona, making him one of the last suppliers in the US.

Word got round with prison authorities across the country, and soon emails were flying around between correctional officers, requesting access to the drugs ordered from the UK.

"May have a secret and important mission for you," read one email between Scott, the boss of San Quentin Correctional Department, and his officer, Tony.

"I might need one of your SoCal guys to go to Florence, AZ and pick up a quantity of the drug and drive it to SQ."

The exchange happened in McWilliams's office.

The men who came, he says, "might have been in a rock band as opposed to being a couple of people coming over from California department of Corrections… they had real big beards".

Afterward he received an email from the California team: "You guys in Arizona are life savers - Buy you a beer next time I get that way."

Mr McWilliams thought they had cracked their hunt for life-ending drugs but most of the shipment from London was confiscated by the US Food and Drug Administration because of licensing issues.

Some vials of the drugs, however, had already been used to carry out executions in Arizona and Georgia.

Testing the untested

In 2011, the UK made it illegal to export drugs for use in capital punishment.

Without a steady supply of sodium thiopental coming from the UK, the search continued for years. Controversially, some states even tried different drug combinations in executions.

Joel Zivot, an associate professor at the Emory University School of Medicine who has campaigned against lethal injection procedures for the past decade, said drugs and other medical tools should not be used in executions.

"No serious pharmaceutical company is producing medicines with execution in mind. When the Department of Corrections uses medicine to kill, it is a misuse of that product," he told the BBC.

He said that rather than end production of drugs that have other therapeutic purposes, governments ought to step in and pass regulations that restrict how these drugs are used.

Some, including Mr McWilliams, who supports the death penalty, thought that the new drug combinations had different effects than the original formula.

"The original drug cocktail that people use - everyone knew it worked well and there was no issues with it. Some of the other drugs weren't quite as effective, so that did cause executions to last longer," he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLawyers for convicted murderer Joseph Wood sued to halt his execution over concerns about the supply of the drugs used in Arizona. The Supreme Court eventually allowed his execution to go ahead in 2014, but the procedure took almost two hours and resulted in him being injected 15 times.

That led Arizona to temporarily halt executions to review the state's procedures. Capital punishment only restarted in the state in 2022.

Charles Ryan, director of Arizona's department of corrections, said in a statement after Wood's execution: "Once the inmate was sedated, he did not grimace or make any further movement." He said he "was assured unequivocally that the inmate was comatose and never in pain or distress".

Also in 2014, the execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma failed and he died shortly after of a heart attack. Some blamed a previously-unused drug cocktail that was used, while reports also suggested a problem with the IV used to administer the drug.

The failure was condemned by the UN and President Barack Obama, and helped shine a harsh light on capital punishment in the US - the only democracy in the western world to still carry out executions. Many have argued the use of newer drugs and combinations of drugs violated the US constitution's prohibition against "cruel and unusual" punishment.

But despite concerns, the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld the legality of the death penalty - and the use of lethal injection drugs.

Decline in death penalty

Today, the death penalty continues, but it has declined steadily, and concerns about the methods used remain.

Oklahoma is one of just five US states to have actually carried out an execution in 2023.

Right now, there are approximately 2,400 prisoners in US penitentiaries on death row. At the time of writing, 20 prisoners had been put to death in 2023, down from its modern-era peak in 1999 when there were 98 executions carried out by 20 states across the US.

More than 60 global pharmaceutical companies won't allow their drugs to be used in capital punishment.

Without reliable access, five states - Idaho, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Utah and South Carolina - have passed laws to allow prisoners to choose to die by firing squad as an alternative.

Deborah Denno, a professor of law from the Fordham Law School in New York City, says the difficulty of obtaining lethal injection drugs is one of the reasons for the decline in the number of executions.

She said executions have always had an "element of secrecy associated with them. But that secrecy became more pronounced" after drug shortages became widespread.

Some states even brought in laws to keep information about what drugs were being used a secret, like Georgia's Lethal Injection Secrecy Act in 2013.

This raised concerns, she said. Although she does not oppose the death penalty, she is critical of the methods currently being used.

"They will say that they have secrecy as security issues to protect what goes on inside a prison. But there's absolutely no reason why we can't know what kinds of drugs are being used."

Paul Cassell, a Professor of Law at University of Utah who supports the death penalty, said the drug issue has been seized upon by campaigners.

He believes the shortage of lethal injection drugs is "used as a kind of choke point to block the death penalty".

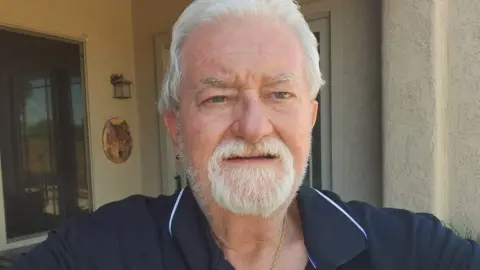

Randi Workman

Randi WorkmanBoth Randy Workman and Carson McWilliams are now retired.

Mr McWilliams was involved in 29 executions while working for the corrections department.

"I didn't grow up thinking, hey, this is what I want to do for a living. It's just what happened to my job."

Mr Workman still lives near the Oklahoma State Penitentiary on a small farm, about two hours outside Oklahoma city.

It's a quiet spot, and a world away from the high security jail filled with 1,200 inmates where he spent his working life.

He is happy in retirement, relaxed and cheerful. He loves his wife and his goats, but he's also held onto some memorabilia from his time working in corrections, including a knife confiscated as prison contraband.

Reflecting on his years spent hunting down life-ending drugs, Mr Workman said "it was a horrible problem. It was like dealing with a dope dealer".

He supports the death penalty, but was "ready to get out of it" and now does pastoral outreach in prison.

"I don't like watching people die. I don't care what they've done. They're still people," he said.