Flight PS752: Families of victims met with harassment from Iran

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThree years after the downing of Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752 in Tehran, families and friends of those who died are still pushing for accountability. But they have been greeted with multiple hurdles along the way, including threats to their safety.

Reza Akbari is one of many Iranian-Canadians who lost a loved one on 8 January 2020, when Flight 752, destined for Kyiv, Ukraine, was shot down by two anti-aircraft missiles after it took off in Tehran.

All 176 were killed.

As the former president of the Iranian Heritage Society in the city of Edmonton, where 13 of the victims lived, Mr Akbari has pushed for Iran to be held accountable for the deaths.

But ahead of one planned demonstration in October, Mr Akbari felt fearful for his safety.

He had been receiving frightening and suspicious phone calls from strangers. In one instance, he believed he was being followed by two men when he was out walking in a deserted part of town.

While the men only asked him for directions, he took it as a sign that he was being watched by people close to the Iranian government.

"Was it a coincidence? I don't think so," he added. "I thought that was a sign that they could come whenever. That they have eyes on me and have people all over."

Mr Akbari has reported this incident and others to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and he is not the only one.

Several Iranian dissidents have spoken out in recent months about being harassed and intimidated on Canadian soil, saying they have been monitored and followed at protests or have had their social media or email addresses hacked.

Others, like Kaveh Shahrooz, a Toronto-based human right lawyer who sits on a legal advisory committee for families of Flight 752 victims, say their loved ones in Iran have been visited by agents in the country as a result of them speaking out abroad.

Canada's spy agency - the Canadian Security Intelligence Service - confirmed to the BBC in a statement that they are aware that Canadians, especially those in diaspora communities, are being monitored and intimidated by "hostile state actors, including the Islamic Republic of Iran".

"The tactics and tools used for such purposes include cyber espionage and threats designed to silence those who speak out publicly against them," CSIS spokesperson Eric Balsam said, adding that the agency is investigating these incidents.

Iran has been accused of harassing dissidents in other countries abroad, including the US and the UK. Last November, Met Police guarded the offices of Iran International, an independent Farsi-language news channel in the the UK, after British intelligence intercepted discussions of planning actual attacks against dissident journalists. The regime has also harassed BBC Persia journalists in the UK, prompting BBC lawyers to file a complaint to the UN.

In 2021, the FBI said it was looking for a man alleged to have hired private investigators to spy on people speaking out against the Iranian regime in all three countries.

Iran has no formal relations with Canada, and has not commented publicly on the CSIS probe. The BBC has reached out to Iran's foreign ministry for comment.

Hamed Esmaeilion, who lost his wife, Parisa Eghbalian, and their nine-year-old daughter Reera on Flight 752, said he has been the subject of harassment and attacks on social media since he began advocating for his family and other victims three years ago.

He said he believes the intimidation tactics from the Iranian government are part of "a propaganda machine against anyone who is standing in front of them."

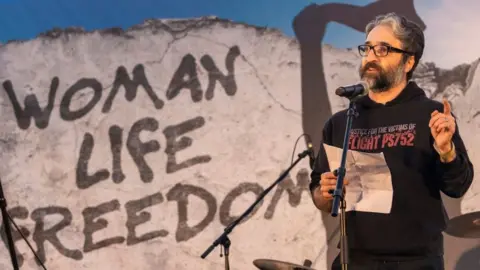

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite these threats, Mr Esmaeilion and others have continued to push for a coordinated international effort to have Iran answer for what happened.

They have also lent their support to Iranians who have taken to the streets by the thousands, calling for freedom and justice, following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini last September after she was detained by Iran's morality police.

"People are recognising more and more that all these crimes are connected," Mr Shahrooz said. "It didn't start with Mahsa Amini, or even the plane. These crimes go back 43 years with the birth of the Islamic Republic."

Of those who perished on the flight, 138 had ties to Canada, including 55 citizens and 30 permanent residents. The dead included 29 children, 53 university students, four newlywed couples, and eight entire families.

Iran's Civil Aviation Organisation has blamed the downing of the plane, which occurred amid heightened tensions in the region following the US killing of top Iranian General Qasem Soleimani in Baghdad, on "human error".

But in a 2021 report, Canada said Iran's government was "fully responsible" for the incident, though there was no evidence to suggest it was premeditated.

In the three years since the tragedy, the victims' families have explored multiple avenues to get answers from Iran, including taking the unusual step last year of filing a case in the International Criminal Court, which does not typically hear from civilians.

In its filing, the families argued that the downing of the plane was a war crime and part of systematic attacks on civilians amounting to a crime against humanity, Mr Shahrooz said. Their case, however, has yet to be heard.

A separate effort to have the International Civil Aviation Organisation probe the incident reached a significant milestone in late December, after the governments of the UK, Canada, Ukraine and Sweden announced they had jointly requested that Iran submit to binding arbitration, arguing the missiles that downed the flight were launched "unlawfully and intentionally".

The Iranian government now has six months to respond, a spokesperson for Canada's foreign affairs ministry told the BBC. If it fails to do so, Canada and the coalition countries will move to litigate the issue before the International Court of Justice.

The move is a big step forward for the victims' families, who say the fight for accountability has consumed their daily lives in the last three years.

"I used to like to travel, I used to go golfing, but I don't enjoy it any more," said Kourosh Doustshenas, a Winnipeg man who lost his fiancée, Forough Khadem, on Flight 752. "What I do now is I want to make sure: could I write another letter to somebody? Did I forget something?"

"On a personal level, I need closure, and the only way I can have closure in my life is if I know the truth."