What we do and don't know about the FBI search of Trump's home

Getty Images

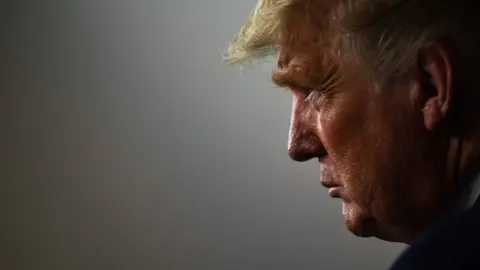

Getty ImagesWhen Donald Trump's Florida home was searched by the FBI, it unleashed a political firestorm unlike anything in recent memory.

The story is complicated and many questions remain. Here's what we know so far.

Why did the FBI search Mar-a-Lago?

In short, because the US Department of Justice suspects the former president may have committed a crime.

The department is conducting a criminal investigation over the improper removal and storage of classified information.

On 8 August, FBI agents gathered evidence as part of this investigation into whether Mr Trump improperly removed government records from the White House and took them to his Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago.

It's worth noting here that US presidents must transfer all of their documents and emails to a government agency called the National Archives once they leave office.

And earlier this year, that agency said it had retrieved 15 boxes of papers from Mar-a-Lago which Mr Trump should have handed over when he left the White House. That discovery is what triggered the ongoing investigation.

In the affidavit released on 26 August, officials said there was "also probable cause to believe that evidence of obstruction will be found at the premises".

That is key, because to obtain the search warrant, prosecutors had to persuade a judge that they had probable cause to believe a crime may have taken place.

What did the agents find?

Thirty-three boxes worth of material, according to a detailed inventory made public in September.

The FBI seized 18 documents labelled top secret, 54 marked as secret and 21 deemed confidential. Agents also found 90 empty folders marked classified or for return to government staff.

The cache also included files marked "TS/SCI", a designation for the country's most important secrets that if revealed publicly could cause "exceptionally grave" damage to US national security.

The classified materials were also mixed inside boxes with personal items such as books and clothing, according to the inventory.

EPA

EPABut the court records do not indicate what information these documents contain and there is much we do not know about them.

For example, other materials taken include a binder of photos, a handwritten note and unspecified information about the "President of France".

It is also not clear why these files were taken to Mar-a-Lago in the first place.

What has Trump said?

The former president has been vocal about the FBI search and has repeatedly denied wrongdoing.

Following the release of the detailed inventory, his spokesman said at the raid had been a "smash and grab".

Mr Trump has previously said the documents taken by the agents were "all declassified" and had been placed in "secure storage" - although the affidavit revealed that the justice department had warned Mr Trump his storage was not suitable for classified material.

Mr Trump also said he would have turned the files over if the justice department had asked for them.

However, the New York Times reported that the department had actively sought additional documents from Mr Trump in the spring that it believed may have been in his possession. It said it was not clear why the recovered files were not handed over at this time.

Mr Trump has also offered shifting explanations as to why the documents were at Mar-a-Lago. He has suggested that evidence may have been planted and insisted they were declassified.

It is questionable whether it matters - in a legal sense - whether the documents were declassified. More on this later.

So how does classification work?

There are three main categories of classified material - confidential, secret and top secret. These are given depending on the extent to which officials deem the public release of the material would damage national security.

When materials are classified, they are marked as such and only certain people - those who have passed the relevant level of security vetting - should be able to view them. There are also rules dictating how classified information is transported and stored.

Some senior officials do have the power to declassify documents. The president, too, has the authority to do this, but would usually delegate the task to those who have direct responsibility for the material.

It's worth noting that documents related to nuclear weapons cannot be declassified by the president, as they fall under a different law, according to a security specialist who spoke to the Washington Post.

As the BBC's US partner CBS reported, the president cannot declassify documents by simply saying so. A written memo would usually be drafted and signed by the president, before a consultation process takes place with the relevant agencies.

Once a final decision is made, the old classification level would be crossed out and the document marked as "declassified on x date".

It is unclear whether Mr Trump followed the typical process with the documents recovered from Mar-a-Lago.

Does it matter if the documents were declassified?

In a legal sense, probably not.

That's because prosecutors are investigating three potential crimes. These are:

- Willful retention of national defence information

- Obstruction of federal investigation

- Concealment or removal of government records

Crucially, none of the three criminal laws in question actually depend on whether or not the files were declassified.

This means it is uncertain whether Mr Trump's argument about declassification would hold up in court or even be considered relevant by a judge.

There are also elements of this story beyond declassification that could prove relevant. There are laws designed to prevent national security documents from being mishandled, for example, while the Presidential Records Act dictates that presidents risk committing a civil offence if official records are not preserved.

What will happen next?

Judge Aileen M Cannon, a Trump appointee, has appointed Raymond Dearie as an independent legal official known as a special master to review the seized evidence.

Mr Trump's team argued that a special master is needed because some of the materials are protected by executive privilege, which allows presidents to keep some communications a secret. The justice department, in turn, argued that an independent arbiter is unnecessary as most of the evidence has already been inspected by investigators.

Mr Trump, meanwhile, has not been charged with wrongdoing. It remains unclear whether charges will be brought as a result of the investigation.