Life after Guantanamo: 'We are still in jail'

BBC

BBC

Mansoor Adayfi knew next to nothing about Serbia when a delegation from its government came to visit him in 2016, in his 14th year in the prison at Guantanamo Bay.

The only thing Adayfi did know was that Serbian forces had massacred Bosnian Muslims in the Balkan wars of the 1990s. All of the prisoners set for release from Guantanamo that year knew this part of the history, Adayfi said, and no-one wanted to go to Serbia.

By that point, Adayfi had been in Guantanamo all his adult life - picked up in Afghanistan aged 19 and held without charge until he was 32. The previous year, the US had officially downgraded its assessment of him to acknowledge that it was unclear whether he had ever been connected to al-Qaeda, and he had been cleared for release under a complex system of classified deals to resettle detainees abroad.

Adayfi wanted to go to Qatar, where he had family, or to Oman, which had gained a reputation at Guantanamo for treating former detainees well. But when the time came for his delegation meeting in the designated room in Camp Six, Adayfi found a Serbian team waiting for him. He listened to them, he said, then gave them a polite no.

"I told them thank you very much, but I know the history."

According to Adayfi, the head of the delegation assured him that Muslims were welcome in Serbia. The government was going to treat him like a citizen, they said - help him finish his education, give him financial assistance, and arrange for a passport and ID. They were going to help him start over.

After the meeting, Adayfi told the US officials at Guantanamo that he did not want to go. But they were frank about the extent of his influence on the process, he said.

"A state department envoy came to see me after the delegation meeting and she said, 'Mansoor, you have no choice. You are going to Serbia.'"

Getty Images

Getty Images

Adayfi is 39, charismatic and quick to smile, with a childlike quality he attributes to being locked away at the moment he was becoming an adult. His long journey to Belgrade began in Yemen, where he grew up in a rural village without running water or electricity. As a teenager he moved to the capital Sanaa to finish school and study computer science. According to his account, he travelled to Afghanistan in 2001 for an assignment as a research assistant, arranged by an educational institute in Sanaa.

Four months after Adayfi arrived, the US invaded Afghanistan and began hunting for members of al-Qaeda. Leaflets were dropped from planes promising large cash rewards for turning people in. Adayfi says the car he was travelling in in northern Afghanistan was ambushed by militants, just days before he was due to return to Yemen, and he was taken captive and handed to the US.

Adayfi's first stop was an American black site, where he says he was stripped naked, beaten, interrogated and accused of being an Egyptian al-Qaeda commander. From there he was flown, hooded and shackled, to Guantanamo Bay.

His 14 years in the notorious prison are recounted in Don't Forget Us Here, a memoir published late last year. It chronicles torture, psychological abuse, and the death of his brother and sister while he was incarcerated. He taught himself English from scratch in the camp, as well as some computer science and business theory. But the story ends shortly after his release, as he lands in Belgrade in the dark one night in July 2016 and is taken by the secret service to a small apartment in the city centre, where he later found surveillance cameras, he said. Adayfi stayed awake that first night, wondering what lay ahead of him.

"I was exhausted but I couldn't sleep, hungry but I couldn't eat," he said, sitting in his current Belgrade apartment late one night in February. "There was loneliness in Guantanamo, but this was a new kind," he said.

What came next is what Adayfi calls "Guantanamo 2.0" - an isolated and restricted existence in Serbia, which he is not allowed to leave and where he says he is followed by police who warn off anyone he tries to befriend.

Half a dozen former Guantanamo detainees across different countries - all released without charge - described similar experiences: lives in limbo; limited by a lack of documents, police interference, and travel restrictions that confine them to a country or even a single city, making it hard to find work, visit family or form relationships.

"Welcome to our life," Adayfi said. "This is life after Guantanamo."

The resettlement deals spread the former detainees across the globe - to Serbia, Slovakia, Saudi Arabia, Albania, Kazakhstan, Qatar and elsewhere. Some had the relative good fortune of being repatriated to their home nations, including the UK, others were sent somewhere alien.

Adayfi was barred from returning to Yemen, where his family lives, because the US congress decided it was a security risk to return detainees to what it deemed unstable countries. Yemen has also refused to grant Adayfi a passport, and so has Serbia, so he is effectively stateless, marooned in Belgrade.

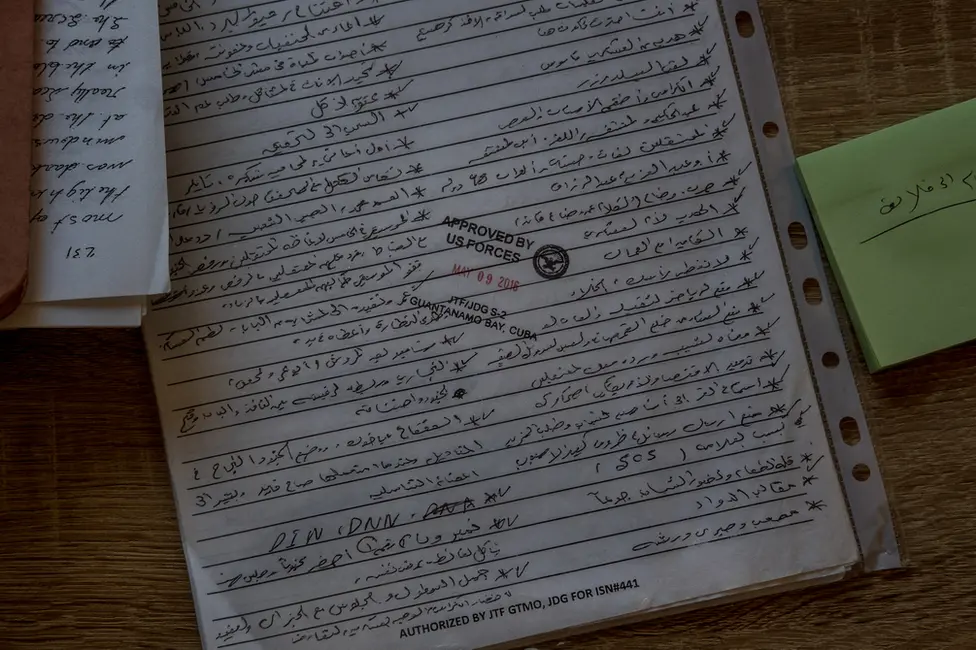

The deal that took him there, like a lot of things about Guantanamo, remains shrouded in secrecy. "I don't know anything officially, because the United States does not tell the lawyers anything," said Adayfi's lawyer, Beth Jacob, a New Yorker who has now represented nine Guantanamo detainees pro-bono. "Most of the information I have about my clients I cannot share with them because it is classified as secret, and what I have is heavily redacted - five-page documents with a few words floating in a sea of blackness."

The US state department told the BBC that it obtained assurances from all third countries that the former detainees would be treated humanely, as well as "security assurances designed to mitigate the threat a former detainee may pose after transfer" and a "framework to facilitate a detainee's successful reintegration into society". The state department had on occasion assisted with the costs associated with supporting former detainees, a spokesperson said - though the amounts involved and the duration of the assistance remain unclear. Serbia's government did not respond to the BBC's questions.

To Adayfi, the resettlement deal feels like an invisible net. He is not sure where it begins and ends. He cannot leave Serbia because he has no passport, and he cannot leave Belgrade without applying for permission in advance. He is followed by police, he says, and has found listening software installed on his government-issued phone. He is not allowed to drive, so he rarely attends Friday prayers anymore because it involves a long round trip by bus to the nearest mosque. He has a residence permit, and he has received financial assistance for rent and further education, but it is difficult to find work because he cannot explain away the 15 years he spent in Guantanamo, so he struggles to make ends meet. He lives in an apartment found for him by the government in a suburb of the city where there are few other Muslims and no places to buy halal meat. He mostly eats at home alone, and to break his loneliness he takes the bus to a nearby shopping mall and wanders around.

When he passes young families there, Adayfi often stares for too long. "I cannot help myself," he said, one day, on a circuit of the mall. "I feel like a shell, empty within."

Shortly after he arrived in Belgrade in 2016, Adayfi gave his first interview to US media and told them he was unhappy about his new life. In response, a widely-read Serbian tabloid published a full-page story referring to him as an "al-Qaeda jihadist" and "convicted terrorist" who was ungrateful to his host nation.

Those he has tried to befriend have been warned off by police, he says. He has screenshots of WhatsApp conversations in which people described these interactions to him - from his first solitary visit to a cafe, a few weeks after he arrived, when police apparently questioned a group of Libyans at an adjacent table, to his most recent interaction, last year, when he had coffee with a young Muslim man he met at the mosque.

"They stopped him and asked him, 'Do you know Mansoor from al-Qaeda?'", Adayfi said. "In the end I told him to delete my number. I don't want anyone to get hurt."

After an interview with PBS Frontline in 2018, Adayfi was taken in by police and beaten, he said. Two friends from his language course were also arrested. A woman from a phone repair course he took was confronted by officers after she spoke to him in the library, he said. He still has messages she sent him afterwards, asking why plainclothes police were warning her off.

And so Adayfi spends most of his time alone in his apartment. He rarely engages with his neighbours, and he has been going to the mall less, he said, since he was seen praying in an outdoor area last year and escorted off the premises by police.

"After a while you give up, you withdraw," Adayfi said. "But it means you are isolated. I mostly live inside my head now."

Adayfi's closest substitute for friends in Belgrade is an international network of former Guantanamo detainees he has helped to connect and which he calls "the brothers", who communicate through various WhatsApp groups or over the phone. The content of the groups is largely apolitical, to avoid putting anyone at risk in their host countries. "We sing songs, tell jokes, share photos, talk to each other about our health. We share memories of Guantanamo - the clothes, the food," Adayfi said. "It helps keep us going."

Among the former detainees Adayfi talks to most is Sabry al-Qurashi, a fellow Yemeni who spent nearly 13 years at Guantanamo before he was forcibly resettled to Semey, a small city on a former nuclear test site in far-eastern Kazakhstan which he is not allowed to leave.

Al-Qurashi was transferred to Kazakhstan in 2014 with four other former detainees, including Asim Thahit Abdullah Al Khalaqi - who died of kidney failure four months after arriving - and Lotfi Bin Ali, who couldn't get the medical care he needed in Semey for a heart condition, and died of heart disease last year after being deported to Mauritania.

With Bin Ali gone, al-Qurashi remains alone in Semey, where he "lives in a state worse than jail", he said. He has written letters to the Kazakh president and prime minister, US embassy and ICRC asking to be set free or sent back to Guantanamo, but received no replies. The Kazakh government did not respond to the BBC's questions.

"Guantanamo was better than here, because at least there I had hope I would one day be in a better place," al-Qurashi said.

"When the government delegation came from Kazakhstan, they told me I would be treated like a citizen of Kazakhstan. But it was a lie. I have no status, no ID, no family, and no friends. I am stuck here and there is no end."

Al-Qurashi is often stopped by the police when he leaves his apartment, he said, and asked to produce ID he does not have. Sometimes he is taken to the police station and forced to wait seven or eight hours until someone from the ICRC comes to get him. He needs specialist medical care for damaged nerves in his face after he was punched by a plainclothes policeman for refusing to remove his jacket one day, he said, but like his old friend Lotfi Bin Ali, he has been refused permission to travel to the capital to get it.

"I went to the police station to ask what happened to the guy who hit me, and they said, 'Shut your mouth, you are nothing here, go home.'"

The incident summed up his existence in Semey, al-Qurashi said - a life lived totally at the mercy of the local authorities, who regard him as a convicted terrorist. "The first pain is the punch," he said. "The second pain is that you have no access to justice. You have no rights."

Al-Qurashi was never charged by the US, which alleged that he was a member of al-Qaeda who attended a training camp in Afghanistan. He was arrested by Pakistani security forces at an alleged al-Qaeda safehouse in Karachi, but he denies he was ever a member of the group.

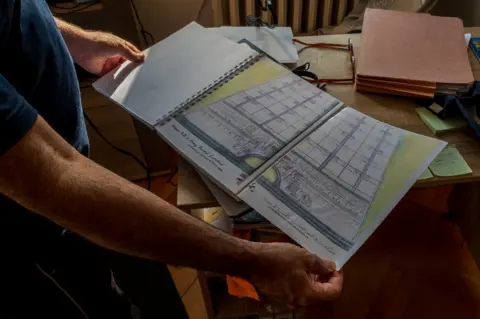

During his detention in Guantanamo, al-Qurashi began painting, producing a large volume of work which was subsequently confiscated. He has tried to maintain the practice in Semey. It is "the only thing that keeps me sane," he said. He is not allowed to order anything online, so his access to paint and canvases is limited. He was asked to contribute work to an exhibition of art by former detainees, but he has no Kazakh ID card and is unable as a result to get the work authenticated as his own and sent.

"I asked the ICRC, should I burn my paintings?" al-Qurashi said. "They told me their only job was to make sure I had a roof and food, and that was it."

Seven years ago, al-Qurashi was married, by family arrangement, to a woman in Yemen, whom he has never met because he is not allowed to leave Semey and she cannot travel to Kazakhstan to live with him. He has pleaded with various Kazakh authorities for permission to leave but his situation remains unchanged. "I have been waiting for seven years for my life to begin," he said.

In total, 779 men passed through the detention camp at Guantanamo Bay. Twelve have been charged with a crime. Only two have ever been convicted. According to a 2006 analysis of US defence department data by Seton Hall University law school, just 5% of the 517 detainees left in the prison that year had been actually detained by US forces. Eighty-six per cent had been detained either by Pakistan or the Northern Alliance militant coalition in Afghanistan, and "handed over to the United States at a time in which the United States offered large bounties for capture of suspected enemies". This was Adayfi's fate, he says - caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. "I was a package deal," he said, "sold to the US and then sold to Serbia".

In a 2007 Guantanamo administrative review board, seven years into his detention, Adayfi stated that he was a "jihadist" and a "son" of Osama Bin Laden, and it was an "honour to be an enemy of the United States". He claims now that the outburst was a protest. The administrative review boards were pseudo legal hearings at which the detainees had no lawyers present.

"We didn't understand the review board, we thought it was another interrogation," he said. "For us, everything was an interrogation. So I thought, today I am going to beat them, I'm going to tell them, I am your enemy."

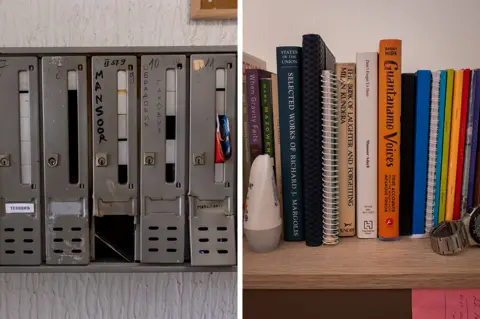

Adayfi had emerged by that point as an informal leader of fellow detainees - organising hunger strikes and other protests. He earned himself a nickname among the guards, "smiley troublemaker". He also devoted himself to education, teaching himself fluent English from scratch, and to writing. He wrote his memoir of Guantanamo twice. The first version, written on contraband pieces of paper, was confiscated and destroyed. When he realised that legal letters were privileged, he sat for hours in the camp classroom, his feet shackled to the floor, and wrote letters, which later became the basis of his book.

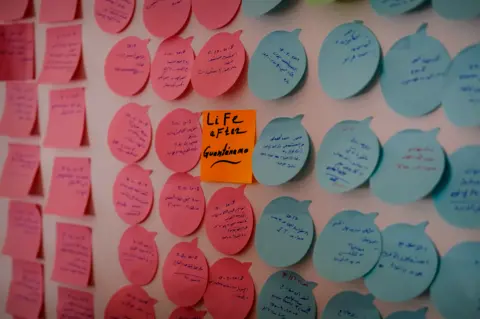

Adayfi is now working on a new book charting the struggles of his post-detention life in Serbia. One wall of his Belgrade apartment is filled with colourful sticky notes describing events that will make up its contents. The notes record interrogations by police, thwarted attempts to make friends and find a wife, and efforts to draw President Biden's attention to his plight. Every day he communicates with other former detainees - more than 100 in total - across various online and WhatsApp chat groups. Many have faced the same sorts of restrictions as Adayfi.

"The United States has created a uniquely terrible situation for these men," said Daphne Eviatar, director of security and human rights at Amnesty USA. "Many of them were tortured and have received no acknowledgement, no compensation, no real rehabilitation," she said. "To then transfer them into another situation where they are restricted, can't travel, can't earn a livelihood, can't move on - it's unconscionable."

To Adayfi, the only path to a new life after Guantanamo is to find a wife and have a family of his own. It is what he thinks about at night when he has run out of distractions. But efforts to meet someone in Serbia have not been a success. His faith dictates that he must marry a Muslim woman and meet her in a traditional way, through her family, but his attempts to integrate into the Muslim community in Belgrade have failed, because of a pervasive fear in the community, he says, of being associated with terrorism.

Adayfi did find a match in 2019, with a woman abroad, he said. She was from a good family, and they communicated for a year while he appealed to Serbian authorities for permission to travel to join her. She was his first love, he said. In the end he begged the authorities to allow him to go to her, he said, but they refused. Eventually, her family ran out of patience and she married another man.

"The worst pain I ever felt was not the black site, it was not the 15 years in Guantanamo, it was when I lost someone I loved," Adayfi said.

"At Guantanamo they torture you but they cannot touch your soul. Love is a pain that touches your soul, and you suffer a lot."

In July 2004, more than two years after the first prisoners arrived at Guantanamo, the Pentagon launched its first formal review of the status of the detainees and cleared 38 men for release with "NEC", or "non-enemy combatant" status. The status effectively acknowledged that the men were not associated with al-Qaeda or the Taliban and had not undertaken hostile actions against the US.

Among the 38 were five Uyghurs picked up in Afghanistan that the US said it suspected were members of the East Turkestan Independence Movement - a small militant group dedicated to independence for the Chinese region also known as Xinjiang. It was unsafe to send the men back to their home nation of China, where Uyghurs are persecuted by the state, so the US struck a deal with Albania to take them. They were finally released in 2006 and landed late at night in the Albanian capital Tirana. Their initial joy at being free subsided when they were taken straight to a squalid refugee camp on the outskirts of the city, where they would spend more than a year.

"It was like another world," said Abu Bakker Qassim, a 52-year-old Uyghur now living a quiet life with his family in a poor and run down suburb outside Tirana. "Five years we were in Guantanamo, in the heat, and suddenly we were in Albania in the deep cold. Every day we dressed heavily and ate tasteless food among the strangers in the camp."

Qassim denies ever being a member of the East Turkestan Independence Movement. He was travelling to Turkey via Pakistan when he was picked up by militants, he said, and handed to the US. Like Adayfi, Qassim and the other former detainees bound for Albania were promised financial assistance, passports, citizenship and apartments that were ready for them, they said, only to discover a very different reality on the ground.

"Guantanamo had six camps at that time, and the refugee camp in Albania was camp seven," said Zakir Hasam, an Uzbek detained in Guantanamo from 2002 to 2006. "There were four or five people to a room, barbed wire around the camp, and we had no money and no good food," said Hasam. "The authorities told us their only job was to keep us safe politically and physically, and that was it."

After a year in the refugee camp, and a series of protests, the former detainees in Tirana were relocated to apartments. They are now further along in their post-Guantanamo lives than Adayfi and al-Qurashi, and in some ways more fortunate. Several have married or remarried. Qassim and Hasam both have children. They benefit from monthly financial assistance for rent and bills and have enjoyed success integrating into their local communities. Their good fortune was to end up in a majority-Muslim country.

But in other ways they live under the same restrictions as the former detainees in Serbia, Slovakia and Kazakhstan. They have no passports or work permits, so they cannot travel or legally earn a living to supplement their modest financial assistance.

"This is not freedom," said Qassim. "Thank God we are out of prison, but we are not free."

Qassim's wife "buys the cheapest vegetables, the cheapest fruits, the ones that are a little spoiled," he said. "We cannot buy in the market because we run out of money in 15 days. So we save wherever we can. We are here alone, we are foreigners, we have no family who can help."

The financial assistance keeps them afloat but it also keeps them in a precarious situation, because it is attached only to the former detainees and not their families. When Qassim's friend and fellow former detainee, Ala Abd Al-Maqsut Mazruh, died from Covid five months ago, his wife Hatiche received a letter from the Albanian government telling her that the assistance would be immediately cut off. She was also told that the government-rented property she lived in with their three young children would be taken back this coming September.

Like Qassim, Ala was released without charge in 2005, after being designated a non-enemy combatant. Hatiche went to the ministry of the interior in person, she said, to plead her case, but wasn't allowed in, and she has not received a reply to her messages. She cannot afford a lawyer. In order to support her three children she will need to find full-time work, while caring for them. Her biggest fear is that she will not be able to shelter and feed her children. Her second biggest fear is that they will persecuted in the future because their father was in Guantanamo.

"I am afraid for my children tomorrow and the day after tomorrow," she said. "I am afraid they will be followed by the stigma of Guantanamo."

The Albanian government did not respond to requests to comment for this story.

"Our biggest problem is we have no ID," said Hasam. "It interferes with every part of life. You have no choices, you cannot choose where to live, you cannot choose to travel to see your family abroad, you cannot choose where to work - everyone asks for ID and documents and your work history," he said.

Hasam goes every week to a sprawling junk market where he looks for electronic and mechanical items he can buy, repair and resell - broken smartphones and laptops, radios, drills, anything he can pry open and restore. But the pickings - and margins - are slim. A two-hour visit to the market one February weekend netted only a single set of damaged speakers.

He wants above all to be able to get a good job, based on his mechanical skills, and provide better for his two autistic children, who cannot currently get proper care. He found out in 2020 that his name was listed on "World Check" - a global database that meant nothing to him at the time but is used by banks everywhere to screen customers for criminal backgrounds. Being listed on the database can limit a person in ways they cannot see, and Refinitiv, the company behind it, doesn't inform those who are listed.

It emerged that year that many former Guantanamo detainees had been added to the database, many to its "terrorism" category despite never having being charged with a crime. Now, with the help of a British legal firm, they are slowly getting small payouts. Hasam got $3,000. Qassim got $3,000. Mansoor Adayfi hasn't received a payout yet, he is disputing the offer. "When you take into account that the lawyers take 30%, it's not much," he said.

Last month, Adayfi was cut off without explanation from the money transfer service Western Union. He had been using the service to send small amounts of money home to his family in Yemen to help pay for his mother's monthly medical expenses, he said, as well as receive donations or payments for work from abroad. Citing company policy, Western Union said it could not disclose to Adayfi or the BBC why he was cut off. A spokesman said the company "takes its regulatory and compliance responsibilities very seriously", and had reached out to Adayfi about his case.

Adayfi is convinced that it is Guantanamo. The long shadow of his extrajudicial detention has been cast over so many parts of his life that he sees it everywhere.

"It follows you every place you go," he said, ruefully. "America punishes you for 15 years, and then the rest of the world punishes you for the rest of your life."

One night back in February, a few days after the 20th anniversary of his arrival in Guantanamo, Adayfi was setting up his apartment to give a video talk to a group of students in the US state of Virginia about the art produced in Guantanamo. He moved his small writing desk in front of his preferred Zoom background - the wall of post-it notes that chart the structure of his new book - and took a silk orange scarf from a hook and tied it around his neck. Orange was the first colour Adayfi saw when his blindfold was removed at Guantanamo - the colour of the jumpsuits the men were forced to wear, that came to symbolise America's human rights abuses at the camp.

He clicked on a cheap ring light he purchased online for these kinds of appearances and it lit up one corner of the apartment. Adayfi rarely turns down an offer to give an interview or talk - he has a book to promote, and he sees it as his responsibility to educate younger generations about Guantanamo. And it brings people into his life, briefly.

Adayfi gave an introductory talk about the catalogue of art produced by Guantanamo detainees and the artists' ongoing battle to take their work out of the prison with them. Then he encouraged the students to ask questions. Many of the school and university age groups he talks to have a hazy understanding of what happened at Guantanamo and how the story began, and Adayfi has to remind himself that most of them weren't born when he was sent there.

Adayfi has probably, by this point, been asked just about every question there is to ask about Guantanamo. But he cheerfully engaged with each one. "At what point did you give up?" a student asked.

"There was no giving up, the moment you give up you have lost," Adayfi said. "We paint and they take the paintings away. We write and they destroy our words. We hunger strike and they break the strike. We hunger strike again. I wrote my book twice. They first time they took it away and it broke my heart. But I wrote it again."

Adayfi completed his manuscript in Belgrade, with the help of an American writer, and it was published at the end of last year. He has also finished a bachelor's degree in business - his thesis an analysis of the successes and failures of former detainees re-entering social life and the labour market wherever they were sent. Guantanamo still circumscribes Adayfi's world - there is hardly anything he does that is not an exploration of or battle with the consequences of his detention.

When the online talk was over, Adayfi clicked off his ring light and rearranged his apartment. It was late at night but he wanted to talk. The conversation turned again to family, and at one point Adayfi began mimicking a father trying to corral his small children and get them to behave. Soon he got carried away with the fantasy, jumping up to chase his imaginary son and daughter around the room, beaming with a wide smile and laughing as he called out their imaginary names. Then he caught himself, and stopped, and sat for a while in silence.

For Adayfi, turning this fantasy into something he can touch will be the only real escape from Guantanamo. Until that day, he is locked in the strange phase of his life defined by his long extrajudicial detention. "No matter what I do, there will be suspicion around me," he said, dejectedly. "People just cannot believe that America would make a mistake."

In April, Adayfi's lawyer received a cryptic email from his government minder, telling her the government was "done with Mansoor" and the "programme was finished". She asked the minder if that meant the restrictions on Adayfi's ability to work, drive and travel would be lifted. He replied to say it would be discussed at the next meeting of officials. Nearly six years after Adayfi was sent to Serbia, it was the first acknowledgement - albeit tacit - that the restrictions against him even existed. They are waiting to hear back.