Japanese internment camps: How a long-lost kimono unearthed a family secret

BBC

BBC Eighty years ago, the US government began rounding up Japanese Americans, forcing them to live in prison camps for the remainder of World War Two. Now the younger generation is fighting to make sure this dark chapter is not forgotten, writes Elaine Chong for the BBC.

When Shane "ShayShay" Konno's grandfather passed away in 2013, the family went back to the house to sort through all of his belongings. In the garden, the storage shed was so full that only one person could squeeze in at a time. As the nimble teenager, it was Konno's job to go inside and pass out the bulkier items to family members who took things back into the house.

Buried deep in the farthest shelf was a beige, cardboard suitcase with a "University of Michigan" sticker on the lid. Opening the suitcase, Konno saw there was some fabric inside, "Oh, a fancy tablecloth," Konno thought.

Once inside, Konno pulled the fabric up to pull it out in front of everyone - it was a kimono, a traditional formal Japanese robe.

Everyone was taken aback by the gleaming royal purple fabric, and how it caught the light with white, peach blossoms hand-embroidered with silver thread.

"I'd never seen a kimono with my own eyes, let alone touched one," Konno, who uses they/them pronouns, told the BBC.

In total there were seven silk kimonos in the suitcase. No one in the family recognised them, which meant the treasures had been secretly kept in the suitcase all this time.

When Konno examined the suitcase more carefully, under the University of Michigan sticker was an unfamiliar name: "Sadame Tomita" crudely written with white paint, along with five digits underneath, 07314. Someone had deliberately covered them up with the sticker.

"That was your grandmother's Japanese name," said Konno's uncle suddenly. "And this was her family's registration number for the camps."

Konno had never met their Japanese grandmother, as she had died before they were born. She was Nisei, a second generation Japanese American who had been a teenager in the incarceration camps. After the war, she went by a Western name, Helen.

It was the one suitcase she was allowed to bring into the camps, Konno later learned. She'd kept it her whole life.

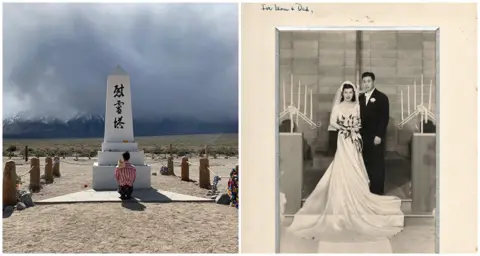

Konno Family

Konno Family

Her husband, Konno's grandfather, had also been a teenager when he was interned at the Camp Amache Relocation Center in Colorado. They met after the war.

Konno says that while they wanted to learn more there and then, they felt discouraged from bringing up the subject in the past.

"My grandmother kept secrets even from her own children. Why would someone cover up their own name? Why hide these kimonos?"

Konno says they are not the only ones with these questions.

At a candlelight vigil for Stop Asian Hate, amid the rise of anti-Asian attacks in the US last summer, Konno could tell that there were other Japanese Americans present, and there was something they wanted to get off their chest.

"The first question we asked each other was: 'What camp were your family interned at?'" Konno says.

"The second question was: 'How much did your family tell you?'"

"I never got the chance to talk to my grandfather about his experience while he was alive," Konno says. "If I ask (my aunt) questions, she is adept at changing the subject. My dad and uncle think digging up the past won't really change anything. Out of respect to my family, I don't press them for answers."

Some of the Issei, first generation Japanese immigrants, and Nisei kept their experience in the camps a secret as they didn't want to pass on painful memories to the next generations. The Japanese term shikata ga nai translates to "it can't be undone".

Konno's dad and his siblings are Sansei, or third generation.

"For Dad's generation, it's not hard for them to not ask too many questions. The trauma happened to their parents. To them, this isn't a piece of history that you can read," they say.

That's why Konno says it's up to them, the Yonsei or fourth generation, to keep this legacy alive.

"I'm of the generation that's far enough away to look at the past differently - and also shout about this injustice."

Konno Family

Konno Family

On 19 February 1942, two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, US President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorising the "evacuation" of Japanese Americans from communities along the west coast, ostensibly to safeguard against spying.

In actuality, the laws were motivated by racism, war hysteria, and fear. No Japanese American was ever convicted of treason or a serious act of espionage during World War Two.

Canada, Mexico and several countries in South America also had similar programmes.

Between 1942-1946, about 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated from their homes to live in government-run camps.

Thousands were children and the elderly. Several prisoners were shot and killed by guards.

More than half were US citizens - anyone with more than 1/16 Japanese ancestry was eligible for internment, which meant that if you had one great-great grandparent who was Japanese, you could be rounded up from your home and sent to live miles away.

In a matter of months, 10 camps were built in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas.

While they were under construction, families were often sent to makeshift "assembly centres" - temporary housing located on fairgrounds with horse stables around the racetracks.

Each family was assigned a horse stall to sleep.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Konno's grandmother was sent to San Mateo Race Track.

"The horses had only been moved the day before, because the smell was so bad," Konno would later learn. "By the time they were relocated, the camps must have seemed nice in comparison."

It wasn't until 1988, almost 50 years later, that US President Ronald Reagan issued an apology and reparations of $20,000 each (about $40,000 or £30,000 today) were paid to more than 80,000 interned Japanese Americans or, in some instances, their heirs.

Brian Niiya, who teaches about the history of the camps at the University of California-Los Angeles, says that at the time, the Japanese American community was happy about the apology and the settlement.

"It was such a longshot, and people never thought they would see this in their lifetime," he told the BBC.

But the complicated legacy of the camps means that there is still a lot of work to be done. "A lot of people still don't know about the history of the camps, but progress is being made," Mr Niiya says.

California has recently passed legislation about putting ethnic study programmes in high schools, where this history will be taught. Textbooks specifically on this history are being published, various National Parks Services are erecting memorials, and screenings of films about the camps on the anniversary help too. In Mr Niiya's current class, several of his students are embarking on their own projects about their grandparents who survived the camps.

"We hope that by the 100th anniversary, every American will know about the camps," he says.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Konno has taken it upon themselves to learn about this legacy. When they found their last name in a book about the camps, they felt pride at first that their ancestor had done something worthy of being recorded.

"My family wasn't just a part of the Japanese American community, but they were helping to lead too," they said. "When I read the full passage, I felt quite sick."

Fearing they would be seen as foreign, some communities burned their Japanese belongings to blend in more.

Their great-grandfather, Konno learned, had visited a nearby Japanese community to convince them to cull their artefacts, destroying family photographs, letters, and documents with Japanese writing.

A thick Japanese dictionary took a week to burn. Sashimi knives and kendo equipment were also added to fires because people thought that the authorities might regard them as Japanese weapons.

Konno realised "my own family helped make that horrible decision to destroy these sentimental items - and it was all for nothing because they were forced into these camps anyway".

The destruction of their Japanese culture would affect generations to come. Konno's grandparents spoke Japanese, but after their experience in the camps they decided to not teach her children the language.

"Grandma thought speaking Japanese wouldn't set her children up for success in America."

Now, Konno is trying to recover generations of lost knowledge. "I can empathise with the choices my grandparents made, they did what they thought would protect us," they said.

Konno family

Konno family

In 2019, Konno asked a friend with a car to make a special pilgrimage. "I wanted to finally go to Manzanar."

Now a museum run by the National Park Service, Manzanar was the first Japanese American internment camp built in the US. Located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California, most residents came from Los Angeles, about 230 miles (370 km) away.

Even though Konno had seen photographs of camps in the past, it was still a shock to see the conditions, recreated for historical education, in real life

Families were housed in long wooden barracks, dividing the rooms with bed sheets. Even with some semblance of privacy, people would still be walking through other people's areas where they slept.

White sheets swayed, with the wind rattling the wooden walls and dust coming through the cracks. "They would have to sweep the room twice a day to get rid of the dust," Konno was told.

The camps were surrounded by 8ft-tall barbed-wire fences that curved inwards at the top. There was no getting out.

Konno's grandmother and her two sisters were teenagers while at the camp. She was incarcerated from the ages 15 to 18, three sisters sharing space with their parents in the makeshift room.

The communal bathrooms were open plan, rooms with shower heads and toilets with no walls, affording no privacy. Women would patiently queue outside to let the person before have their own private time, which meant people would shower at weird times all night long.

Looking outside of the barracks, Konno saw remnants of the Japanese Zen gardens.

"They were trying to make this hostile prison just a bit prettier for themselves."

Konno translates the Japanese term gaman which means "to endure seemingly unbearable hardship with dignity".

"In these camps, Japanese American families were treated as less than human. But they still tried to respect and help each other in this horrible place," says Konno, bitterly.

What they didn't realise was that years ago, their father had also visited Manzanar, stopping by after dropping them off at university.

"He went to Manzanar on the drive back, absorbed everything, and kept it quiet to himself," Konno says, amazed.

Now Konno understands that the previous generations pay respect in their own way.

More recently, after Konno began their own search for answers, Konno's father and uncle made a detour to drive to where their paternal relatives had been temporarily imprisoned at the Merced Assembly Centre.

The camps have been long razed to the ground, but the fairground still stands. A statue of a little girl sitting atop of a pile of suitcases serves as a memorial to the families who had been imprisoned there.

On a wall behind her, the individual names of the 1600 Japanese Americans, including the babies born into the camp, have been engraved in stone. Konno's father and uncle stopped to find their family name and took photos to send to Konno.

Konno family

Konno family

Looking back, Konno wonders if part of the reason it took them so long to start this research was because they assumed their questions would not be welcomed. But what they've learned is that the other generations had the same questions too.

"Opportunities to have these conversations 80 years on are vanishing, I feel that it's even more urgent now to find things out for myself, not just hear second-hand stories," they said. "Adding more to my life to-do list."