Does the skyscraper still have a future?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesChina has restricted construction of very tall buildings, calling them vanity projects. It comes at a time when offices across the globe are filled with empty desks and some workers are wary of sharing hermetically sealed spaces. So does the skyscraper still have a future, asks author Judith Dupré.

Ninety years ago, after the world had survived a global pandemic and was on the brink of a devastating economic downturn, the skyscraper's golden age dawned.

Its breakout stars - the Chrysler and Empire State buildings - were the tallest structures ever built and captured the public's imagination.

The Chrysler's spire, secretly assembled inside the building, emerged in a legendary coup, winning the tower the coveted title of "world's tallest" in 1930. A year later, the Empire State took the title, but the enormous building was slow to lease, so slow that it was called the "Empty State Building" until King Kong, a 1933 film about a lovesick gorilla who scales the building, premiered and filled its floors.

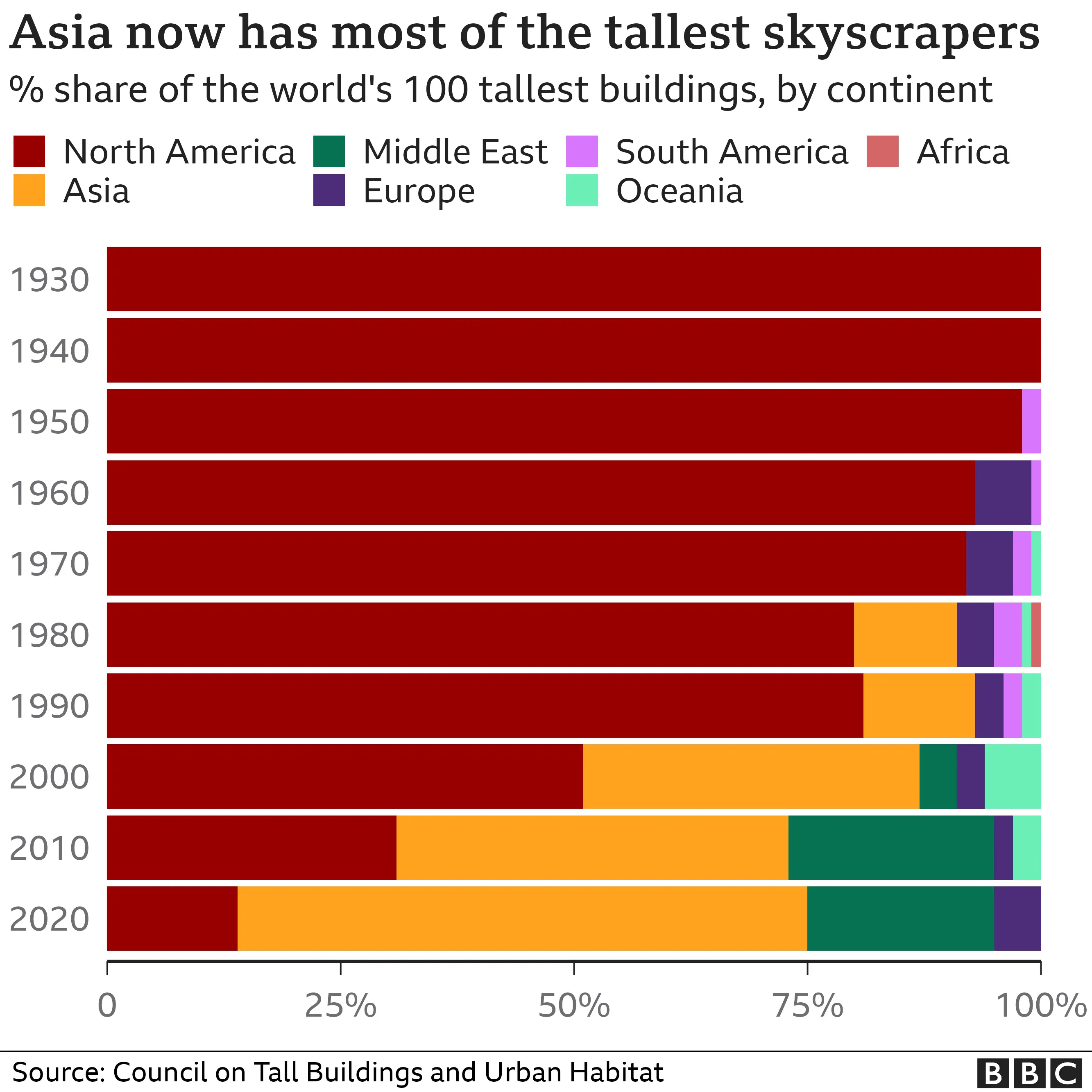

Skyscrapers' second golden age has been under way for the last 20 years, although construction everywhere has slowed or paused. There was a 20% decrease in the number of tall buildings completed globally in 2020, compared with the previous year, according to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. This is most evident in China, where, until recently, towers were going up at a breakneck pace.

So will a post-Covid world still be building skyscrapers?

They've been written off before. After 9/11, the tall tower was declared dead, a wildly premature prediction. More skyscrapers have been built in the last 20 years than were built in the century previously, and they are safer, stronger, and greener than ever, thanks to the rigorous building standards that were adopted globally following the attacks on the Twin Towers.

A nation's fortunes can pivot on its claim to the title of "world's tallest." Just as Petronas Towers put Kuala Lumpur on the map, the Burj Khalifa, the tallest structure on Earth, transformed Dubai from a remote desert outpost into a prosperous global destination.

Such towers also spur new development. "Burj Khalifa anchored a 300-acre parcel of many, many buildings, and it worked," says Adrian Smith, a founding partner of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, whose high-performance towers include the Burj Khalifa and Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia, which is set to become the world's tallest when completed.

Still, designers are questioning the formula: high density populations + high land values = high buildings - that once drove construction. There has to be a good reason to build a 500-metre building, says Kamran Moazami, a managing director of WSP, whose portfolio includes the tallest building in London (The Shard), the tallest in the US (One World Trade Center) and tallest in Asia (Shanghai Tower).

"You have to ask what is the best possible, most economical way to build. Extreme height can create a destination, as in Dubai, but is not needed in well-known cities like Shanghai or Manhattan. Today, an iconic tower is judged not only on its appearance but on its carbon use."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut, icon or not, not everyone is a fan of skyscrapers, particularly the glassy new ones.

They cause "aesthetic pollution," says architectural critic David Brussat. "Somehow, as architecture grew taller, it grew smaller. People are depressed by the boring urban canyons they must walk to get to work." Earlier skyscrapers, he says, were designed at street level to delight passersby, and they invited a "reciprocity in civility that was important to everyday interactions".

Covid upended everything that makes urban life desirable - vibrant public places, mass transit connectivity, and easy access to restaurants, museums, and clubs. But now cities are coming back, some more quickly than others, and the people who build skyscrapers predict that they will be back too, just not quite like they were before.

"The pandemic showed that neighbourhoods with a diverse mix of residential and office buildings were able to weather a prolonged shutdown better than others," says Scott Rechler, chair and chief executive of RXR, one of the largest owners, managers, and developers of real estate in the New York region.

"It spurred structural shifts in the office market with more companies seeking newer, trophy buildings, what the industry refers to as a 'flight to quality,' and older office buildings becoming competitively obsolete." Older buildings are being converted to new uses, he adds, like residential towers, making business districts more diverse.

"By no means is the office market dead," says Rechler. "Talent has come back to New York City. They want to live and work here. The demand for 21st Century, highly amenitised office spaces is as high as ever."

New York City's aggressive public health response, which has yielded an 87% general vaccination rate and a 90% rate among the building trade unions, has helped meet that demand, he says. And the spaces inside the office buildings are also changing according to post-pandemic needs - more fresh air, sunlight and open spaces.

More are being designed for collaboration, rather than side-by-side desks, says Moazami. "Demand won't lessen, but the way an office is populated will be different. You can no longer assume a Monday-to-Friday schedule for all employees. You may need more space for fewer people."

Urban demand for outdoor areas has skyrocketed.

For the ultimate outdoor experience, there's City Climb in Manhattan, the world's highest external building climb. The fearless (and harnessed) can scale the exterior of 30 Hudson Yards, a 387-metre tower, when City Climb opens in November.

Climb Images

Climb ImagesSkyscrapers live in big cities, so their future depends on workers returning. Not everyone wants to come back - working at home in yoga pants has its advantages -but underlying, elemental forces make a return inevitable.

We are a social species. Pre-pandemic studies showed that emotional isolation - loneliness - can cause mortality risks as high as those posed by smoking. Moreover, magic happens when human beings, especially creative ones, work in proximity. "We now know that remote work is productive, but people need to come together to collaborate," Moazami said. "You move, you absorb, you learn."

There are other costs to working remotely, particularly in industries that are highly visual and spatial. "Communication by computer can be challenging, in terms of giving direction and controlling the work product. Clients find it hard to understand a building model seen on a screen," says Smith.

Historically, crises have sparked innovation. For tall buildings, the post-pandemic era could be different, if China, the leader in skyscraper construction, is any gauge. To put its explosive growth over the last two decades into context, consider this: worldwide, there are 115 "supertalls," buildings over 300m (984ft). China has built 85 of them.

China is hunkering down, using strategies that will fill its vacant skyscrapers, recover its economy, and bolster its Covid-bruised national identity.

In 2020, following a string of earlier construction rulings, the government announced sweeping height and design restrictions on new skyscrapers. In a lateral move, they prohibited "copycat" buildings, replicas of Western landmarks like the Eiffel Tower, the Kremlin, and others that are found throughout China.

In July, bans tightened again, now aimed at height: new buildings taller than 500m were prohibited and those taller than 250m were strictly limited. Most recently, China has banned buildings taller than 150m in cities with fewer than three million inhabitants. This has had financial repercussions, particularly for Western architectural firms, which have built many of China's supertalls.

"China has overbuilt in every sphere - residential, office towers, satellite cities - projects that didn't have to be built, but were to keep their population working and grow productivity," says Smith, whose firm has designed five major skyscrapers in China.

The government recognised "they'd better start building towers that make economic sense and can be rented. In other words, they began thinking like a US developer." Skyscrapers cannot grow an economy, they can only meet an existing need. That said, eight of the 10 tallest buildings now under construction are in China.

Skyscrapers convey power, economic might, and technical prowess - attributes that are irresistible to nation builders.

The pandemic has compelled more expansive thinking about tall buildings and the people who work in them, calling for flexibility, adaptability, access to nature, and towers that conserve more and consume less.

Judith Dupré is the author of Skyscrapers, A History of the World's Most Extraordinary Buildings, and many other books on the built environment