Hollywood union workers vote to authorise strike

BBC

BBCThe union that represents some of Hollywood's most important workers has voted to approve a strike in a move that could shut down nearly all US film and television production.

Members of the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE), which covers camera crews, prop masters, hairdressers and other craft workers say they are being worked to death with gruelling hours and no guaranteed rest or meal breaks.

Members are demanding better work conditions, as well as fairer pay from streaming services to cover their share of labour.

Over 50,000 workers voted overwhelmingly - 98% in favour to 2% against - to approve a work stoppage. Should they carry out the stoppage, the strike would be the biggest labour walkout in Hollywood since World War Two.

Negotiations between the union and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers broke down last month after the IATSE walked away from a deal.

The deal would have improved wages and rest periods, the Alliance said, and included a nearly $400m (£293m) pension and health plan.

However, with the vote, the union has "spoken loud and clear" said its president Matthew Loeb.

"This vote is about the quality of life as well as the health and safety of those who work in the film and television industry," his statement Monday said. "For those at the bottom of the pay scale, they deserve nothing less than a living wage."

After months of pandemic lockdowns in 2020, Hollywood's film and TV sets have been booming in recent months - and crew members say the hours and demands placed on them have become worse than ever.

Like many around the world, Hollywood's crew members are re-evaluating how and when they want to work.

On the streets of Los Angeles and on social media, Hollywood crew members have been sharing harrowing stories of 15-plus hour days, with claims of working more than 70 and 80 hour weeks.

Some spoke of having "work done" - surgeries to rebuild backs and knees - failed marriages and missed weddings and funerals.

"Fraturdays" are said to be a common occurrence in the entertainment industry - workers start on Monday mornings at 06:00, and on Fridays, start late in the afternoon or evening and work until Saturday morning. It leaves little time to do anything but sleep all weekend.

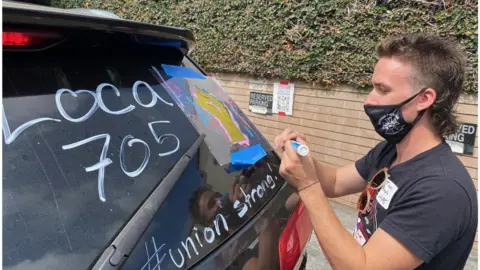

"My hours are insane," sound mixer Thomas Pieczkolon said during a rally on Sunset Boulevard as he decorated cars with chalk "Vote Yes" signs. He works on a $300m show for a streaming service and has to work nine hours most days before they even break for lunch, he said.

Mr Pieczkolon recently worked a nearly 18-hour day on a Monday and his friend Jade Thompson, a costume dresser on the show, fell asleep at the wheel driving home.

"I nodded off and then came to and drifted off to the side and had a panic attack," she said. "It wasn't even the end of the week! It was a Monday."

Workers have claimed that is a common problem - the adrenaline of a long day leaves them and the tiredness kicks in on the drive home.

"Sometimes you don't even realise until you're already in your car on that long ride home by yourself," Ms Thompson said, adding that her colleagues have WhatsApp group chats to make sure everyone gets home safe.

The authorisation vote does not necessarily mean that a strike will take place. Most workers who spoke to the BBC said they hoped it would instead be the leverage their union needed to negotiate better deals.

The last time Hollywood shut down for a labour dispute was the writers' strike in 2007 and 2008 amid the rise of reality TV and the soaring popularity of reality television stars like Donald Trump.

Today, producers are under pressure to make a deal with workers. More than 100 members of Congress have urged them to implement more humane conditions.

The authorisation for a strike could also set up a showdown with streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon, which union members said were taking advantage of their work.

"Streaming companies are getting a discount on our labour," said set decorator Lisa Clark. "We deserve a fair share of that profit - we deserve to be paid at least what we used to be paid when we used to do network television."

Streaming services have transformed the industry with ambitious sets and epic shows and storytelling. Workers love that streaming shows look incredible like feature films, Ms Clark said - but she gets 10 weeks to prepare hundreds of sets which would have taken six months for a feature film.

"It's not a reasonable request," she said.