Canada election: What you need to know about the campaign

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCanadians are going to the polls on Monday to vote in an early general election. Can Prime Minister Justin Trudeau manage to win his sought-after majority?

For the second time in two years, Canadians are voting in a federal election.

Mr Trudeau launched the campaign mid-August, two years ahead of schedule as he seeks a third term in office.

The campaign was a five-week sprint as all the party leaders made their pitches to voters, whose turn it is now to cast their ballots.

Here is what you need to know about the campaign.

It's a tight race between two frontrunners

Mr Trudeau said the election was necessary because it was a "pivotal moment" for the country to choose the next steps in the pandemic recovery.

Over the summer, opinion polls also indicated his Liberals were in a good position to win a majority of seats in the House of Commons.

The last time Canadians voted federally, in October 2019, the Liberals only had a narrow election win.

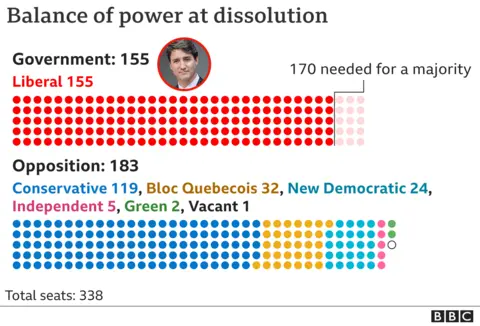

Mr Trudeau, the 49-year-old leader of the centre-left party, formed government with a minority, meaning he had to rely on opposition parties to help him pass his legislative agenda.

Soon after Mr Trudeau's August election call, support for the Liberals began to fall even as the fortunes of the Conservatives, the main opposition party, rose.

New Conservative leader Erin O'Toole is running in his first federal campaign at the helm of the centre-right party. He begins the race as an unknown to many Canadians, but his pitch to moderate voters helped him gain traction.

A few factors were an early drag on the Liberals' popularity.

Canadians questioned the need for an election as the pandemic engulfed the country once more. Old political scandals also dogged Mr Trudeau on the campaign trail.

From early September the two parties have been locked in a statistical tie for first place, each at about 30% support in national polls, indicating another minority government is likely.

That means each party's ability to get their voters to the polls will be a crucial factor in the final results.

It's 2019 all over again

Polling suggests that Canada's main federal parties are ending this short campaign in roughly the same place they did two years ago.

In that election, Mr Trudeau's Liberals won the most seats despite losing the popular vote to the Conservatives.

The Liberals currently have the lead in vote-rich regions like the provinces of Quebec and Ontario, giving the party a potential advantage, pollsters say. The Conservatives have the upper hand in traditional strongholds like Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The left-wing New Democratic Party (NDP), led by Jagmeet Singh, is polling slightly higher than in 2019, making the party a potential kingmaker in the next parliament.

The People's Party of Canada (PPC), a relatively new federal party that received only 1.6% of the vote share and no seats, last time around, has seen a surge in support.

Its populist leader, a former Conservative member of parliament, has tapped into a vein of anger over vaccine mandates and lockdowns measures. The PPC is now hovering at about 6% support.

With support spread across the country, it's not predicted to win any seats but the PPC could siphon voters from the Conservatives.

In the campaign's final days, both Mr Trudeau and Mr O'Toole warned supporters who might be flirting with the NDP or the PPC that it could split the vote in key ridings (constituencies).

The pandemic casts a shadow

Over 27,000 Canadians have died from Covid. Some provinces have been hard hit in the latest surge, especially in Alberta, where hospital intensive care units are close to being overwhelmed.

Alberta has declared a public health emergency and began re-imposing health measures lifted early in the summer.

That's become an issue on the campaign trail, with Mr O'Toole's past praise for how the province handled the pandemic coming back to haunt him.

Meanwhile, Mr O'Toole has attacked Mr Trudeau for his pandemic election call, saying the decision was "selfish" and "un-Canadian".

Vaccinations have also been a hot topic over the past weeks.

Canada has one of the world's highest vaccination rates - over 80% of eligible Canadians have received at least one jab - and provinces have begun to implement vaccine passports.

Mr Trudeau has made his support for mandates a wedge issue. A Liberal government would require Covid vaccinations for bureaucrats, transport workers and most domestic air and rail travel by the end of October - something the Conservatives don't support.

The Liberal leader has been followed across the country by aggressive anti-vaccine protesters.

While Mr O'Toole wants to ensure Canada reaches a 90% vaccination rate, he has faced repeated questions over why he won't disclose whether all his candidates have received the jabs.

Affordability (and all the other campaign issues)

Pandemic management was not the only subject to dominate the campaign trail.

All the main party leaders spoke frequently about affordability. Higher petrol, housing and grocery bills are part of a recipe for economic anxiety among voters.

Stretched household budgets, rising inflation, housing costs, and childcare were front-and-centre.

Party leaders also sparred over healthcare, climate change, and gun control.

They were sometimes distracted from their carefully crafted messages by outside events.

In August, it was Afghanistan. Mr Trudeau called the election the same day the Taliban entered Kabul as American troops pulled out of the country. The Liberal leader was forced to defend Canada's widely criticised efforts to evacuate its citizens and allies.

The health crisis in Alberta has made the final days of the campaign challenging for Mr O'Toole.

In Quebec, controversy over a question during a televised national leader's debate about two provincial laws - one that limits public servants who hold positions of authority from wearing religious symbols at work, another that strengthens language laws in the province - shifted the race in that crucial battleground.

It gave the Bloc Quebecois, which only runs candidates in the province, a mid-campaign boost when leader Yves-Francois Blanchet took issue with the moderator calling the laws "discriminatory".