Three police killings in the US: Is there a better way?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSince the April conviction of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, police officers in the US have killed at least 83 civilians, almost two per day.

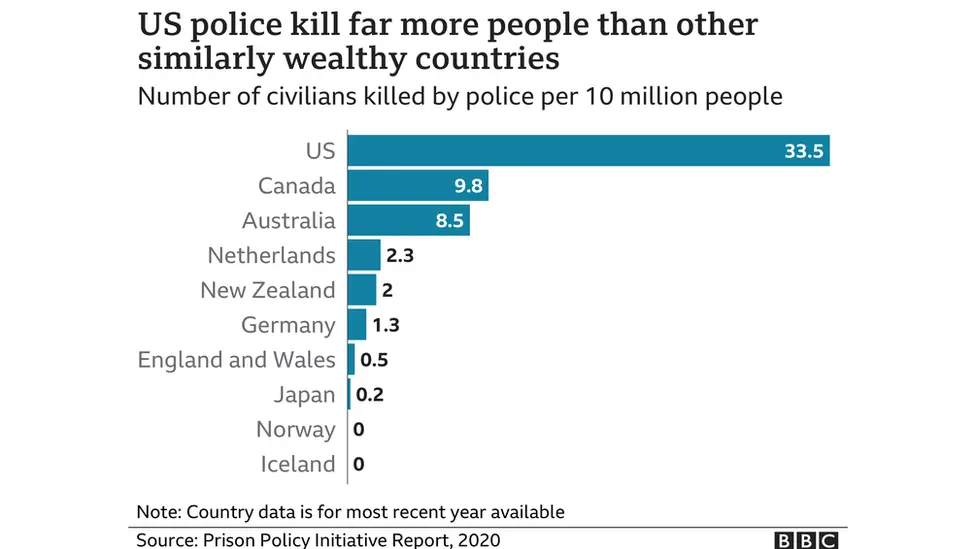

On duty officers in the US kill civilians at a rate of 33.5 people per 10 million annually, according to advocacy group Prison Policy - a higher rate than most wealthy nations.

More police are killed on the job in the US as well, due in part to the proliferation of guns. In 2020, 42 police officers were fatally shot while on duty, according to the Council on Foreign Relations.

But that number is a fraction of the number of civilians killed by police.

In the wake of Floyd's death and a string of other high-profile police killings, campaigners are calling for major reforms to the way police approach interactions with the public they serve.

"Police have lost the benefit of the doubt," says Kirk Burkhalter, a New York Law School professor and 20-year veteran of the city's police department. There is now a blanket assumption that in every case of deadly force, police have done something wrong, he says.

The BBC spoke to Burkhalter and another former officer, Ron Johnson from Ferguson, Missouri, about three civilian deaths at the hands of police.

In each case, they explained how an officer's training should have steered their response, and what might have gone wrong.

Ma'Khia Bryant, 16, Columbus

What happened?

In April, police were called to the city's southeast side after reports of a disturbance. Footage from the day shows Officer Nicholas Reardon arrive as Bryant lunges at another young woman with a knife in her hand.

Officer Reardon shouts "get down" as he approaches, draws his gun and fires several shots, fatally injuring the teen, who was black, less than 10 seconds after he exits his squad car.

Reardon has been placed on paid administrative leave while an investigation is conducted by the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation.

'There's got to be a better way'

Reardon was met with a chaotic scene - a "complete melee", Burkhalter says. There was a crowd of bystanders, many of them shouting. Body camera footage appears to show a girl fall to the grass after being shoved by Bryant before she is kicked by another bystander.

But the commotion alone does not warrant deadly force, says Johnson, a former Missouri State Highway Patrol captain who led the police response in Ferguson following unrest after the death of Michael Brown, an 18-year-old shot by a police officer in 2014.

"It is never too late to try to talk somebody down," he says. When using force "you always start at the bottom tier and work your way up".

Johnson, who now offers leadership training, says in the wake of Bryant's death he received calls from school teachers across the US saying they deal with scenes like this "every day".

"I think sometimes when we train, we forget about the other [non-violent] tools," he says.

"But stepping away from policies and procedures, from a human standpoint, for a life to end in 10 seconds and five seconds in these encounters, it's tough," Johnson says. "It makes us think that there's got to be a better way."

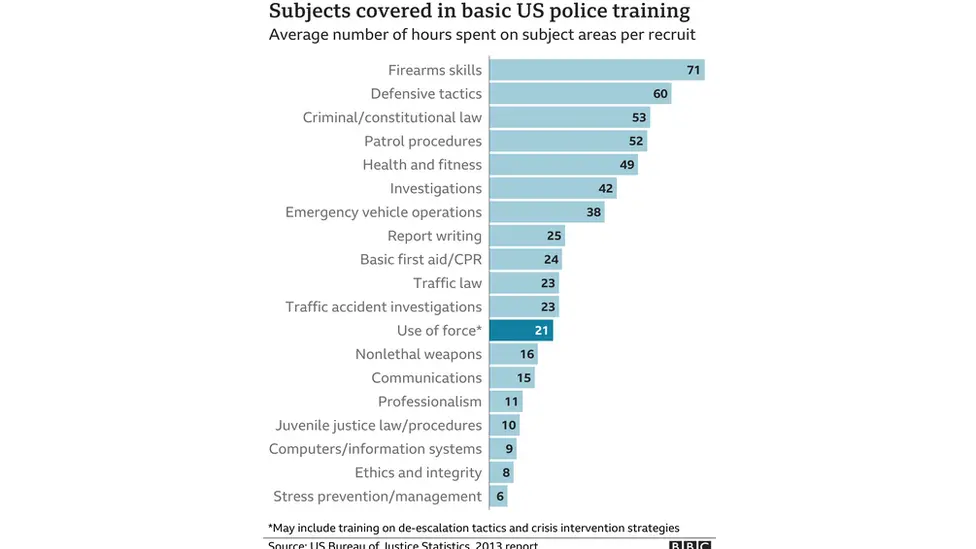

According to a 2013 report (the most recent available) from the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, police academies on average spend the most time - 71 hours - on firearm skills, compared with 21 hours on de-escalation training and crisis intervention.

Burkhalter, like Johnson, described Bryant's death as a "tragedy", but both stopped short of saying the officer acted contrary to police training.

"Faced with someone using deadly physical force against another. What should he do?" Burkhalter says. "This officer was damned if he did, damned if he didn't."

Burkhalter ruled out trying to shoot to injure.

"Hitting a small moving target like that is almost impossible," he says. And a taser would likely have been be "ineffective" in stopping Bryant because of her movement and proximity to the other girl.

"If the police used force every time they were justified in doing so, you would have people dying at the hands of police every single day, multiple times a day," Burkhalter says.

Of those killed by police, black people are more than three times as likely as white people to die during a police encounter, according to a 2020 study by Harvard University. That black people face outsized odds that deadly police force will be legally "justified" against them is a serious problem, says Burkhalter. "Police exercise restraint quite often when it's not a person of colour. And that's where the community loses trust in the police."

Adam Toledo, 13, Chicago

What happened?

In March, officers responding to early-morning reports of shots fired in Chicago's Little Village neighbourhood ended up chasing two suspects down an alley.

Authorities said that one of them, Adam Toledo, was holding a gun as he ran. Body camera footage from the scene follows officer Eric Stillman as he pursues Toledo and shouts for the boy to drop the gun.

According to analysis of the footage, Toledo appears to discard something behind a fence before turning and lifting his hands. In that moment, Stillman shoots him - 19 seconds after the officer exited his squad car.

The body camera footage appears to show that the boy was not holding a weapon in the moment he was shot.

Stillman was placed on administrative leave for 30 days. He has not been formally charged.

A 'split second' decision

Stillman's attorney has said that the officer's actions were consistent with the Chicago Police Department's use of force guidelines and with the law.

According to Burkhalter, he may be right.

Getty Images

Getty Images

There is no national standard for police departments' use of force, but most derive their policies from Graham v Connor - a 1989 Supreme Court ruling that examined police use of deadly force.

According to the unanimous decision - quoted by Derek Chauvin's lawyer at his trial - the "reasonableness" of force "must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight".

This means that an officer's perception of fear could effectively override the actual presence of danger.

So while it is not a crime to own or carry a handgun in Illinois, and Toledo may not have been holding a weapon when he was shot, the use of force could still be justified, Burkhalter says, "by the officer's fear that he could be shot".

"How can we predict whether or not someone is going to use that weapon against you?" he says.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Burkhalter also emphasised that what we see from the body camera footage, days and weeks after the shooting, may not have been clear in the moment.

"It's difficult to know what the police officer saw," he says of the case. "We can all freeze the video and see his [Adam Toledo's] hands are clearly up. His hands are empty. But can the brain really process that information in the way that we all can? I don't know."

But both Burkhalter and Johnson say that even if a shooting were legally or procedurally justified, that does not necessarily mean it should have happened.

"Just because policy says you're justified, or you're authorised, it doesn't mean we're doing the right thing," Johnson says.

Tony Timpa, 32, Dallas

What happened?

In August 2016, Timpa called police from a parking lot. Timpa, who was white, told the dispatcher he was schizophrenic, off his medication and needed help.

Officers arrived to find him agitated and handcuffed by security guards. Body camera footage - released after a three-year legal fight - shows that the officers pinned him face down on the ground for more than 13 minutes.

Timpa pleaded with the officers - Kevin Mansell, Danny Vasquez and Dustin Dillard - to let him go, saying at one point "you're going to kill me". The video shows police mocking Timpa even after he stops moving or making any noise.

Paramedics arrived but were unable to revive him.

The coroner's report found that he died "as a result of sudden cardiac death due to the toxic effects of cocaine and the stress associated with physical restraint". The death was ruled a homicide.

The officers - Mansell, Vasquez and Dillard - were indicted by a grand jury in 2017 on charges of misdemeanour deadly conduct. But these charges were dismissed in March 2019 by the local district attorney. All three officers have returned to active duty.

'Recipe for disaster'

What should the police have done with Timpa?

According to Burkhalter, they should not have been there at all.

People dealing with mental illness may lash out at those around them, Burkhalter says, including officers at the scene, potentially giving police justification to use deadly physical force.

In this case, police argued that Timpa was being aggressive and that force was used to keep him away from a nearby street busy with traffic. The officers pinned Timpa in the so-called prone position - the same one used on Floyd - and placed a knee on his back.

At some point, officers zip-tied his legs.

"It sounds like they [police] were using a technique they would use with someone who was resisting arrest," Burkhalter says of the encounter. But to respond to someone in mental distress "requires extensive medical training" not typically covered by police departments.

Between 2015 and 2020, nearly a quarter of all people shot by police officers had a known mental illness, according to data compiled by the Washington Post. And a study last year from the Treatment Advocacy Center found that those with an untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter than other civilians.

Campaigners say it is a failure of policy.

Law enforcement, they argue, are ill-equipped to address mental health crises and should be replaced with social workers, counsellors and medical professionals.

In response to criticism last year, the International Association of Chiefs of Police said that while police are often "the only ones left to call" in these situations, mental health experts are "more appropriate and safer for all involved".

Burkhalter would agree. Sending an armed officer to a health crisis, he told the BBC, is like "launching a guided missile" and being surprised when it explodes.