China Mac: From attempted murder to leading a protest movement

China Mac

China MacIn July, an 89-year-old Chinese woman was walking through her neighbourhood in Brooklyn, New York, when she was slapped and set on fire.

The two people made away on foot as the elderly woman rubbed her back against a wall to put out the flames. News spread of the attack and it didn't take long to come to the attention of China Mac, a Chinese-American rapper from New York.

Mac, real name is Raymond Yu, decided enough was enough.

"That was home, this was right here, this is Brooklyn. I was watching the clip of her speaking in Cantonese and that's my language. I was hurt, I wanted to do something about it," he says.

Attacks on East Asian people living in the US have shot up during the coronavirus pandemic. Stop AAPI Hate, a group which records reports of Covid-19 discrimination directed at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the US, received 2,808 incidents of self-reported cases from the start of the pandemic to the end of the year.

"I saw a comment saying: 'I bet China Mac isn't going to do anything about this', and I was like 'I actually would, and I am going to do something about this,'" he says.

Mac arranged They Can't Burn Us All protests across the US in a stand against the rise in anti-Asian racism. Leading a protest movement was just the latest step in a remarkable journey for Mac, a former gang member who was once jailed for attempted murder.

China Mac

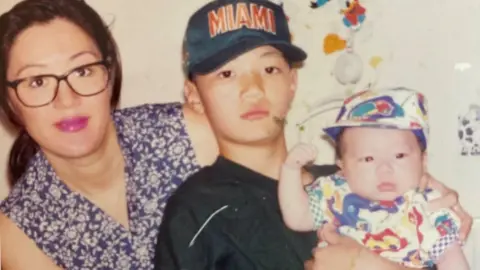

China MacChina Mac was born in the early 1980s in New York to Chinese parents. His father, known locally as Fox, was a high-ranking member of the Flying Dragons gang, notorious in New York for trafficking heroin and its bloody turf war with their Chinese-American rivals, the Ghost Shadows.

"I saw the respect he got. I saw the admiration and fear people had of him. I saw things happening in Chinatown, dead bodies. I had to be very careful where I walked. I remember certain places I couldn't go to," Mac recalls.

Mac describes his early life as a "bubble" in Chinatown. His father wasn't around a lot and his mother, who spoke little English, had to raise Mac mostly on her own while working two jobs.

"I wanted to know him … but I felt like he never really wanted to be with me," Mac says of his father.

A lot changed for Mac when his father was arrested, becoming a federal informant and passing over information about Johnny Eng, or Onionhead, the leader of the gang.

China Mac

China Mac"My father told on him. I remember the shift in the attitude towards me and my mother. Before it was like 'this is Fox's son' and people would open the door for me, I felt like royalty. But after that situation I felt the difference. My mom was scared to walk in certain places, she was always on alert," he says.

"I remember seeing that and I didn't fully understand, but as time progressed I understood the kind of position my father put us in."

By the age of seven, Mac's mother was struggling as his behaviour deteriorated, and he was placed in a group home. This was a world far detached from the isolated upbringing he'd had in Chinatown. He soon realised that the only way to survive in a chaotic environment full of competing children was to fight.

China Mac

China MacIt was here that he discovered hip-hop, realising it was a way to fit in. He spent hours memorising the lyrics to the likes of KRS One, Mobb Deep and LL Cool J. Mac would often recite lyrics in rap battles with other kids.

"I plagiarised it and I was rapping to people. They were like 'Whoa that's crazy' until they realised I was plagiarising, that didn't last too long," he laughs. "But it was the feeling ... and I was like 'that's the response I need, that's what I want.'"

Mac eventually moved back in with his mother before running away. It was then, at the age of 12, he was recruited into the Ghost Shadows - the rivals of his father's former gang. Mac was soon deeply involved in the life that came with being a Ghost Shadow. He was in and out of juvenile detention centres as a teenager for various violent crimes, including robbery and assault.

Then in November 2003, Mac was involved in an incident that would change the course of his life.

China Mac

China MacMac walked into a club in Chinatown and spotted MC Jin, a fellow Chinese-American rapper who was making waves in the world of hip-hop.

One of Mac's friends mentioned that Jin had allegedly disrespected one of their friends. Mac and his friend cornered Jin and a tussle broke out between the two groups. During the altercation someone shouted that one of Jin's associates, Christopher Louie, had a knife, Mac says.

Mac then pulled out a gun, aimed it at the back of Louie's head and pulled the trigger. The gun jammed. He shot a second time and a bullet hit Louie in the back.

"I remember the gun jamming but I wasn't fully in control. While I was doing it, it was a blur, but I do remember what happened. Something else took over me," Mac says.

He left the club and spent the next year on the run.

Mac spent the year moving between New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Detroit and Kalamazoo in Michigan. He spent a period living in student houses at Albany University and Georgia Tech, committing robberies and petty crime to get by. Then, one day, somebody passed him a copy of Blender magazine featuring an article about the shooting and Mac's mug shot.

Mac tried to flee to Canada, but was spotted at the border. The game was up.

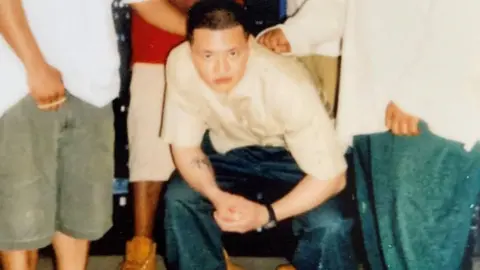

He was taken to Rikers Island, one of the country's most infamous prisons.

"Rikers Island was a zoo. It was dangerous there. My classification was super high. I was in the housing areas where everyone was facing life, murder charges, big charges," he recalls. "I understood Rikers Island. I was fighting all the time, cutting people, always in trouble. It's the culture, we would fight over anything."

Facing life behind bars, Mac saw little point in changing his behaviour.

But when the trial came, his lawyer delivered a presentation about Mac's life and how he was a product of his environment. The judge handed him an 11-year jail term.

China Mac

China MacOne day a few years into his sentence, Mac's mother came to visit him in Sing Sing jail, where he was then incarcerated. She cried throughout the visit, while Mac helplessly tried to comfort her. Back in his cell, Mac broke down in tears. A prisoner sweeping the floor outside leaned on the bars to the cell.

"He said: 'I saw you on the visiting floor and I saw your mother.' At the time he had 27 years in prison," Mac recalls.

"He said: 'I remember when that happened to me, my mother has passed away since then. I just want you to know this doesn't have to define you. This doesn't have to be your last stop. You can turn this into more prison time, or you can use this as a university. You have all the time in the world to learn about whatever you want to learn, to fix whatever you want to fix."

Mac decided it was time to make a change. He started to read and enrolled in every program he could. He even featured in the HBO documentary University of Sing Sing.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMac was eventually released in 2013. He launched a record label, Red Money Records, and opened a pet store that his mother now runs. He started dropping freestyle raps, including one called 0 to 100 that went viral.

After getting recalled to jail for just over a year for violating his probation curfew, upon his release his music started getting more traction. He even recorded a song with one of his heroes, Method Man from Wu Tang Clan. He released his debut album MITM in 2017.

Mac started branching out as his social media following grew to hundreds of thousands. His YouTube show, Mac Eats, where he takes viewers on food tours of New York, was a big hit with fans. An interview with Mac and Jin, where they discuss the night of the shooting for the first time, racked up 1.5 million views.

Then Covid came.

China Mac

China MacSoon after Covid-19 was detected in Wuhan, China, racist abuse started to get hurled at many Asian-Americans. Many accused then-President Donald Trump of adding fuel to the flames with incendiary language, including calling it the "China virus" and "kung flu".

In California, an elderly man collecting cans was threatened with an iron bar as he wept, and a teenager was taken to hospital after being physically assaulted. In Texas, an Asian family, including a two-year-old and six-year-old, were stabbed in a supermarket.

"I was just seeing things online. Videos were being circulated and I saw the man with the cans in San Francisco. I did a video saying that we will raise money for the man. I wanted to do something about it," Mac says.

Then the elderly woman was attacked in Brooklyn. He felt it was time to stand up.

Mac arranged They Can't Burn Us All protests with actor and producer William Lex Ham. Rallies took place in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, with many Asian-Americans turning out. Mac said he took inspiration from the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Philip Ha

Philip Ha"People had to sacrifice, people had to stand up, people had to fight, people had to be uncomfortable. Imagine what Martin Luther King felt at that time? Imagine what Malcolm X felt?" he says.

"Asian people don't have that, there's not enough of it, we haven't had that fight yet. I'm not saying there weren't Asian people who were a part of that movement, there were. But it wasn't the majority. We haven't really stood up and fought for our own yet."

Mac says it was time to use his fight for a positive cause.

"We're not going to take it and we're ready to fight. You're not going to do this to us. That's something I learned in prison, I learned to stand up for myself," he says.

Although the They Can't Burn Us All movement has been a success, Mac admits it could have been better organised.

Despite leading a protest movement, Mac emphatically refutes the suggestion he's now a political activist. "I'm not an activist man. I like to go to the strip club. I like to be in the hood. I'm not built for the political s---," he says.

"But I am built to fight for my people."

China Mac

China MacLooking to the future, Mac says he finds himself in "difficult times", without elaborating. He says he wants to keep bettering himself and "his people".

"I don't know what's going to happen tomorrow. All I know is that I can stay the course," he says.

The next day, Mac wiped his Instagram and deleted most of his music from YouTube. In a post, titled I QUIT MUSIC, he said that he had "reached his ceiling". This week, he travelled to San Francisco Bay Area and took to the streets after reports of more attacks on the Asian community.

Whether Mac heeds calls from his fans to return to music remains to be seen, but whatever he chooses next, his journey has been an extraordinary one.