Michigan 'plot': Who are the US militia groups?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe FBI says it has foiled a plot to abduct Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer by six men involved with an armed militia group. The governor had become a target of anti-government outrage after enacting strict social distancing measures since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

The men discussed murdering "tyrants" and trying the governor for "treason", according to court documents. They met repeatedly over the summer for arms training and combat drills, the FBI said, and co-ordinated surveillance around the governor's vacation home.

And they are among a growing number of paramilitary groups mobilising across the US.

So who are militia men, what do they believe and what does the law say?

What are US militia groups?

The term has a complex history.

The Militia Act of 1903 created the National Guard as a reserve for the Army, managed by each state with federal funding, and defined the "unorganised militia" as men between 17 and 45 years of age who were not part of the military or guard.

Today, the National Guard is community-based and are deployed by the governor of its respective state, often for weather-related emergencies or instances of civil unrest, such as the protests against policing practices earlier this year.

Militia groups, in contrast, do not report to a governmental authority, and many organise around an explicitly anti-government sentiment. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), an advocacy organisation, defines current US militia groups as the armed subset of the anti-government movement.

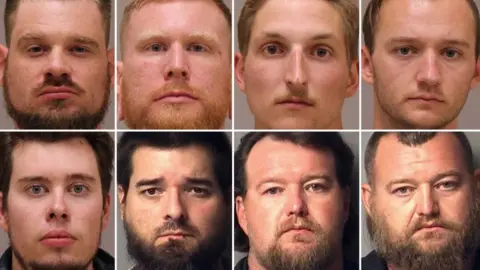

Antrim County Sheriff’s Office

Antrim County Sheriff’s OfficeThese groups engage in military exercises and gun training, and generally believe in conspiracies regarding the federal government.

They focus on protecting second amendment rights - or the right to bear arms granted by the US constitution.

Heidi Beirich, director of the SPLC's Intelligence Project, describes the militia movement as "American, born and bred".

Many of these militia groups hold a "romanticised" view of the US revolutionary era, she told the BBC, with notions that they, like the colonists who fought British rule, are "the ultimate protectors of the nation".

The III% Security Force militia group describes themselves in such a way - a coalition "intended for the defence of the populace from enemies foreign and domestic".

"At such a point as the government intends to use the physical power granted it by those who implemented it against them, it then becomes the responsibility of the people themselves to defend their country from its government," the militia's website states.

While there are militia-type formations in other countries, Ms Beirich says the revolutionary past of the groups in the US has made them more unique when it comes to movements with "conspiratorial ideas of an evil federal government".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat exactly do they believe?

"Their number one issue, no matter what, is about protecting the second amendment," says Ms Beirich.

"These are organisations that believe there are conspiracies afoot to take away their weapons."

Militia are not the same as the white supremacy movement or the alt-right movement, she emphasises.

They are not advocating white rule, for example, though they do share some beliefs with these movements.

Two of the biggest militia incidents in recent years were the Bunkerville standoff - when militia ran federal officials off a rancher's land, believing the government was there to seize cattle - and a similar standoff in Oregon, where militia took over a wildlife refuge in protest of government "interference" in ranchers' lives.

PAUL RATJE/AFP/Getty Images

PAUL RATJE/AFP/Getty ImagesBut in recent years, Ms Beirich says, the militia movement has overlapped increasingly with anti-immigration views.

She notes that those ideas predated Donald Trump's presidency, but his election win emboldened the movement.

"Although these groups have always hated the federal government, they're pretty big fans of Donald Trump, so they're in an awkward position where they support Trump but believe there's a deep state conspiracy against him."

It's a connection that Governor Whitmer referenced this week as she addressed the plot against her, accusing the president of "giving comfort to those who spread fear and hatred and division".

The president argued he should be thanked because federal investigators eliminated the alleged threat against her.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn recent years, militias have begun to work openly with white supremacists, which was rare in the past, Ms Beirich says.

Members of the III% militia, for example, turned up at the far-right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2016.

"That's a toxic brew we have to be concerned about," Ms Beirich says.

And in a report released this week, the Department of Homeland Security said white supremacist extremists remain the deadliest domestic terror threat to the US.

The report echoes testimony from FBI director Christopher Wray in September, saying that "racially motivated violent extremism", mostly from white supremacists, make up the majority of domestic terrorism threats.

How many militia groups are there?

Whenever there is talk of gun control on Capitol Hill, membership rises in militias nationwide.

In 2019, the SPLC identified 576 extreme anti-government groups that were active in 2019, down from 612 in 2018. Of these groups, 181 were militias. Given how secretive these organisations can be, however, that figure is likely an undercount.

"The number of these groups skyrocketed in the Obama era," Ms Beirich says. "Obama never moved on gun control, barely spoke on it, but they viewed him as an existential threat."

A similar situation happened under Democratic President Bill Clinton, she notes. The militia movement views Republicans as a party that is protective of gun rights, unlike Democrats.

In 2008, the last year of Republican President George W Bush's term, the SPLC reported 149 anti-government groups.

The next year, under Democratic President Obama, that number jumped to 512, reaching a peak of 1,360 in 2012.

Is this legal?

Yes, depending on the state in which a militia is located. All states have laws barring private military activity, but it varies when it comes to paramilitary or militia organising.

"There are very few rules in the US about what people with guns," Ms Beirich says. "Many of them frame holding military training exercises as their right with the second amendment, exercising their right to bear arms."

According to a 2018 report by Georgetown University, 25 states criminalise kinds of paramilitary activity, making it illegal to teach firearm or explosive use or assemble to train with such devices with the intent to use such knowledge "in furtherance of a civil disorder".

Twenty-eight states have statutes prohibiting private militias without the prior authorisation of the state government.

"Not all militias are involved in the same kinds of activities," Ms Beirich notes.

"If people are engaged in exercising their constitutional rights under the second amendment in states that don't ban the kinds of activities they undertake, they have every right to engage."