Coronavirus: Are hospital cleaners forgotten heroes in this crisis?

BBC

BBCCleanliness and hygiene has never seemed of greater concern than it is now. So should the people making sure hospitals are free of germs be getting more of a voice?

On 26 March, Chicago stopped for a moment of gratitude amidst the growing coronavirus crisis. People took to their balconies, porches and rooftops cheering and ringing bells in the dark winter night.

The applause was for the healthcare workers, first responders and service-industry employees on the frontlines of the pandemic who were risking their lives every day to save people from the virus wreaking havoc around the world.

But for hospital cleaner Candice Martinez, 39, the recognition of nurses and doctors has left her feeling empty. "It's disappointing to me that us 'lower level employees' aren't getting any kind of recognition for what we are doing."

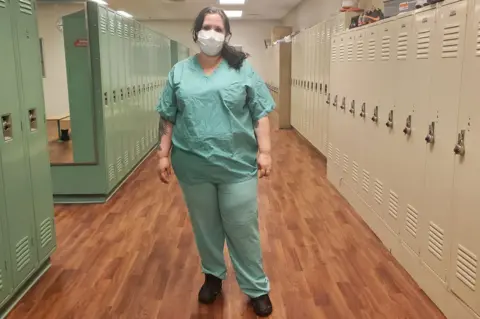

As an Environmental Services Worker (EVS) at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Ms Martinez is responsible for cleaning the rooms while patients are in hospital or after they are discharged or moved. And in the midst of a pandemic defined by the need for cleanliness - it makes sense that the people cleaning the very hospitals where coronavirus victims fight for life are of utmost importance.

Ms Martinez is one of the thousands of essential employees in the city who still have to go to work despite the crisis. And one of the 12,571 cases of Covid-19 identified in Chicago.

"When I got sick I was really scared. I have asthma so I have breathing issues and my lungs are already compromised."

She is one of approximately 33,000 hospital service workers in Chicago, according to a University of Illinois 2018 study, which says they make on average between $26,000-31,000 a year.

"The whole edifice of the hospital system rests on the folks who clean, wash and provide cafeteria services," Dr Robert Bruno, who conducted the 2018 study, told the BBC.

Yet despite their importance, Ms Martinez says that service workers are often the last to learn about new protocols and procedures in the hospital - as may have been the case with coronavirus.

On the frontline in the US

"At the beginning of this pandemic we started raising the alarm bells because hospitals were putting in place work plans but our employees weren't being trained on them," says Anne Igoe, VP of Hospitals for Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

Workers like Ms Martinez are "last on the list," she says. "People overlook them. When coronavirus started in Chicago, nurses and doctors were invited to the morning huddles on new protocols, and that information wasn't always getting to EVS workers," Ms Igoe said.

Ms Martinez's primary responsibility is cleaning rooms after women give birth, work that rewards her with $14.58 (£11.71) per hour.

"We clean and sanitise the room," she says. "We pull trash and clean high-touch spots like light switches and doorknobs."

It's risky business during this pandemic - the virus seems to survive on hard surfaces like door handles for days, and some suggest it's possible it can even survive on clothing and in linens.

Alamy

AlamyMs Martinez, like many other EVS workers, relies on overtime to pay her bills, which can mean starting at 07:00 and finishing at nearly midnight. On these marathon shifts she works at a variety of wards, and she suspects she contracted the virus when a patient room was improperly labelled or a sign cautioning that staff wear personal protective equipment (PPE) was taken down too soon.

"When I started feeling bad a couple of weeks ago I had recently done overtime in the part of the hospital where there was coronavirus. I know that people who were on shift at the same time on the same floor are out sick now too."

She started feeling feverish in the middle of a 12-hour Sunday shift, and then she did something she rarely does - she left work early.

First came the headaches, then the fever, so she called the Covid hotline and got an appointment for a test the following day. With a high fever and a cough, Ms Martinez boarded a bus and then a train for the hour-long journey from her Brighton Park neighbourhood to the testing centre downtown.

Two days later, she received news that she had tested positive for Covid-19.

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

- AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

- HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

- VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- STRESS: How to look after your mental health

Ms Martinez is white but two-thirds of hospital service workers are not. The struggle to protect these low-wage cleaners represents a broader problem, because the virus has disproportionately struck the city's minority communities.

"Chicago's hospitals are being held up, propped up and supported by our most vulnerable, low-wage, low-educated, most-overworked workers who are disproportionately people of colour," says Dr Bruno.

The challenge for workers like Ms Martinez, he adds, is the lack of flexibility that comes with being a low-wage worker which means they have no choice but to return to the place they contracted the virus.

Northwestern Memorial Hospital spokesperson Christopher King told the BBC: "The health and safety of our employees, physicians, and patients is our highest priority. Since the outbreak of Covid-19, we have gone to extraordinary lengths to maintain an environment that protects everyone."

Although it's impossible to know exactly where or how Ms Martinez contracted coronavirus, the hospital has agreed to pay her workers' compensation.

Ms Igoe of the union described the situation for at-risk hospital service workers as chaotic and inconsistent.

"Some EVS workers are called immediately and told they cleaned a room that had a Covid-positive patient, and some are just sent an email which can be problematic if they don't read it for days because they don't have a computer at home."

Many hospitals are trying to limit exposure from infected patients, says Ms Igoe. "Nurses are bringing up more food trays and changing some linens. Housekeeping's main role is cleaning the rooms after the patients have left."

But such efforts may have come too late for workers like Ms Martinez, who says the hospital has asked her to come back to work three days after her symptoms subside.

After over a week off work, she said she is feeling much better and is grateful for the sick leave provided by her employer, but she's not quite ready to go back to work.

"It's going to change my approach when I go back. I probably won't be doing overtime for a long-time because I don't want to be in different parts of the hospital."

And by not working overtime, that means she can expect a lower paycheque.

Days later, Ms Martinez had returned to work, but she fears she may catch it again.