Coronavirus in New York: 24 hours on the frontline

AFP

AFPBy last Tuesday, the death toll from coronavirus in New York City had passed that of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

The figure was reached only three weeks after the first coronavirus death in the city.

The outbreak has placed New York at the centre of the global pandemic and put an unprecedented strain on the city's emergency workers and frontline staff.

Over the course of Tuesday, six of those people - two doctors, an undertaker, two senior care home staff and a food delivery worker - kept diaries of their day and shared them with the BBC.

This is their story.

Midnight, Tuesday 7 April

Kathleen Flanagan returns from a late shift at a nursing home. The TV is on in the living room, playing the sitcom That '70s Show. As has become the custom in her household she shouts "Hello" to let her family know that she is home and to make sure they avoid contact with her.

She heads downstairs into the laundry room, takes off her clothes and showers.

Everything she has worn at work must go into the washing machine before she sees her husband and children.

When she heads back up the stairs, she is greeted by a bouquet of sunflowers in the kitchen. A card from her eight-year-old son reads: "Keep kicking butt Mom!"

Two of her three sons are asleep on the couch waiting for her. She cooks eggs and spinach for dinner and shares details of her day with her husband - the good news is that coronavirus patients in one of the centres she oversees are starting to look better, but in another the situation is getting worse.

She opens her laptop to do some work and falls asleep somewhere between 01:00 and 02:00.

01:57

Doctor Jennifer Haythe is woken by a call from the intensive care unit at her hospital, letting her know about a Covid-19 patient whose condition is deteriorating.

The 46-year-old hangs up the phone and tosses and turns in bed, worrying about the patient. She rethinks the plan for them and then is met by the increasingly familiar feeling of loneliness.

Like many healthcare professionals working with coronavirus patients, Jennifer is living separately from her family. She is staying in an apartment in Greenwich Village, while her husband and children are in their house upstate.

Faced with an eerie silence outside and missing her loved ones, she does a deep breathing exercise: "In for four, hold for seven, out for eight." It must work because she falls asleep.

02:00

Outside the city, in the New York state town of Corinth, Faith Willett, a director of nursing at a care home, is woken by a member of staff reporting a high fever. She advises her to self-isolate and contact a doctor as soon as possible.

Faith feels sick and struggles to fall back to sleep. She scrolls through her phone to see the latest news on the coronavirus outbreak, paying close attention to local updates that might be worrying residents and their families.

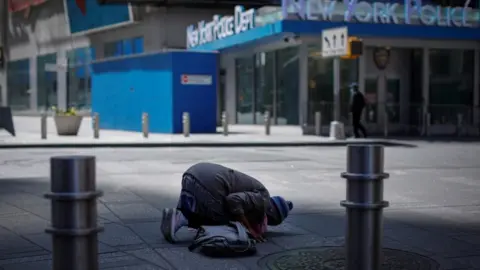

Reuters

Reuters

The news feels so surreal that the 46-year-old nurse wonders if she's asleep. She wakes her husband to ask if she's dreaming. "No, babes, you're awake," he replies. He tells her to get some rest.

After a few hours of disturbed sleep, she wakes to her alarm. She grabs her computer and scans the latest updates from her colleagues. She can breathe a sigh of relief. There are no confirmed cases - for now.

05:00

Funeral director Steven Baxter is already out of the house. His hours have completely changed since the virus struck, as he and funeral workers across New York struggle to keep up with the rising number of fatalities.

The days of wearing a suit to work are gone. He now dons "scrubs" that he can throw out afterwards, without risking cross-contamination. The trainers he wears to work are always kept outside.

He sets off to a nursing home, where he has to collect the body of yet another coronavirus victim. It is the first of several such visits he will have to make that day.

06:30

Back in Greenwich Village, doctor Jennifer Hayth wakes up to her alarm. She opens her eyes with the fleeting hope that the past few weeks have been a bad dream.

She has a shower and gets ready for work. There are no dogs for her to walk, no husband to kiss goodbye and no children to prepare breakfast for.

She heads to a coffee shop where a woman walking her dog notices her doctor's uniform and thanks her. In the cafe, the only other customer - a retired police officer - pays for her coffee.

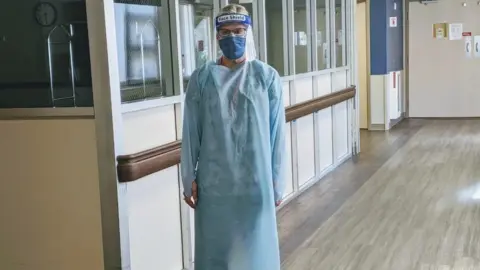

BBC

BBC

The Cat Stevens song Peace Train comes on the radio as she drives to work at Columbia University Medical Center. She hasn't heard it for a while and it makes her feel energised. She looks over the highway at the USNS Comfort - a Navy hospital ship docked in New York City where coronavirus patients are being treated - and thinks to herself that it seems almost majestic.

Arriving at work, she puts on her mask, gown, gloves and other equipment required for working with coronavirus patients and heads over for another day in the ICU.

07:00

Nurse Kathleen Flanagan wakes to a hug from her eight-year-old son. Before she leaves the house, he performs a dance to the song High Hopes by the band Panic! At the Disco.

She listens to it again in the car, applying the lyrics to her own life.

Mama said don't give up, it's a little complicated...

Had to have high, high hopes for a living

As she listens to the song, she passes the traffic light where last month she received a phone call that changed everything. A colleague at a nursing and rehabilitation centre in New York City told her that two residents had fevers and respiratory symptoms - the first signs of coronavirus in any of the six Centers Health Care facilities she oversees.

She was heading to a different centre at the time and was faced with the decision of whether to help remotely or change her plans and put herself on the frontlines of the outbreak. She turned her car around.

Her normal job does not include direct patient care. But three weeks later, she continues to take a hands-on role at the centres with coronavirus patients in spite of the risks.

08:45

At the Glens Falls Center nursing home, Faith Willett has been at work for about an hour and there is already cause for concern.

Before leaving the house this morning, she said her personal mantra aloud to herself in the shower: "We've got this." Like every day in recent weeks, she hoped there would be no signs of coronavirus in the centre.

But as a nurse walked out of a resident's room during the routine morning checks, Faith could tell from her eyes it was bad news - the resident had a high temperature and was getting short of breath while reading her Bible.

BBC

BBC

All the staff at the home know this might end up being the day the virus made its way in. Masks need to be issued and the door to the resident's room must be closed, with only designated caregivers in full protective equipment allowed in.

Faith considers the order.

You should never close a door to a resident's room unless they ask you to - it's a violation of their rights; it's forced isolation; it's mistreatment, she thinks. But she reminds herself that they must go against all their instincts as caregivers to save lives.

A nurse in full protective equipment goes into the room to perform the test. There are tears in the nurse's eyes but they soften as she walks in. She completes the test, packages it and takes it to the lab. Faith admires the woman's bravery for being able to do it.

09:00

Steven Baxter is sorting through death certificates and other documentation at Gannon Funeral Home in Manhattan. The phone line has just opened so he is preparing for another day of calls from families who have lost loved ones to the virus.

The 53-year-old recently converted the chapel in the funeral home into a morgue. He has a rule: the dead need to be treated with respect and given adequate space. But the number of bodies coming in is hard to keep up with.

Later today he will need to take the bodies of eight Covid-19 patients to be cremated, and to chase a supplier about cremation boxes, which are increasingly in short supply.

It will be about three weeks before the person he collected this morning can be cremated - the pandemic has put a strain on the system, creating major backlogs.

All his days are merging into one at the moment. The "removal" this morning was like any other in the time of coronavirus - he put on a respirator and other protective equipment, and used disinfectant spray as he worked to ensure he was safely transferring the body.

09:34

People not directly on the frontline are also performing critical jobs to prevent the virus spreading.

Since the pandemic began, doctor Michael Morgenstern has swapped his subway commute for a walk upstairs. This morning, he logs on to video conferencing platform Zoom for his first appointment of the day.

Many of his patients are elderly and part of his role now is explaining the risks of coronavirus to them, and the precautions they should take.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The first patient wants to go out and visit two other doctors. Michael asks the son, who is also on the call, to try to see if the appointments can be conducted over the phone or through a video platform.

He is concerned about people exposing themselves to the virus and has spent much of his morning up to now working on a petition calling for the public to wear non-medical face masks, in line with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control.

He repeats the mantra "an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure" to himself as he works.

His legs shake as he begins his second appointment of the day. He's nervous about what's happening in the world.

10:00

Faith Willett gets a call from the nurse who fell ill - she can't get tested and has instead been labelled "presumed positive".

Faith is angry about the lack of testing for a frontline worker. She worries that the residents may have been exposed and then finds herself wondering - selfishly, she thinks - if she too might have been.

Five other people working at the home have been tested for Covid-19 because of symptoms - four were negative and the fifth is pending.

Faith and her colleagues all worry about the same thing: they don't want to be the person who brings the virus into the facility.

11:00

At another nursing and rehabilitation home, Kathleen Flanagan has spent much of the morning checking on residents with coronavirus symptoms.

The hospital calls to discuss returning one long-term resident, assuring her that he is alert and responsive.

Two others are at the hospital. One is not doing well. When asked who his next of kin are, she replies: "We are his family."

She urges the doctor to fight for him.

AFP

AFP

11:23

Michael Morgenstern sees his next patient via video call. An elderly person with cancer.

The cancer appears to be spreading but while the patient is continuing with chemotherapy, they are holding off on adding radiation treatment for now because of the Covid-19 risk.

Michael is worried. He advises relatives who are still going outside to consider wearing face masks when they are around the patient.

He continues to see patients and work with volunteers for his coronavirus campaign throughout the morning. One of the patients was born only shortly after the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, he thinks to himself.

12:00

Doctor Jennifer Haythe is carrying out rounds in the ICU. Everyone she sees is a Covid-19 patient. They are all on ventilators.

She passes colleagues but can only see their eyes. In them she sees stress, but also hope and courage.

EPA

EPA

As she attends to sick and dying patients she thinks about what it must be like for them and their families.

"A hospital without visitors. What is that?" she asks herself.

12:30

Sarujen Sivakumar, a 22-year-old Lebanese-born delivery team manager for Eat Offbeat - a catering company led by immigrants and refugees - heads out to work.

Like many businesses across New York, his company has had to re-model amid the pandemic and now sells coronavirus "care packages" of a week's worth of meals and snacks.

As he begins his journey, he is struck again by how quiet the city is. In the six years since he arrived here as a refugee, he has never seen it like this. There are no groups talking to each other, no performers at the subway station. He feels almost as if he is in a video game.

Before the outbreak, he would greet his colleagues with special handshakes and hugs. But as he walks into the kitchen today, he knows he has to keep his distance.

13:00

At the Glens Falls nursing home, it is visiting time.

Faith and her colleagues bring residents into the dining room where there are big windows through which they can see their relatives.

Families wait outside in their cars and take turns coming to the windows. They have agreed to limit their visits to 10 minutes each.

As emotional reunions take place through the glass, Faith observes the range of tears being shed - joy, laughter, sadness and, of course, fear.

13:45

The chefs at Sarujen's company say they are too scared to take the train to work any more, but also worry about how they would survive financially if the company stops running.

Sarujen knows how hard he and others at the company worked to get where they are today. He worries that if it closes, it won't be the same again in the future.

There is little time to talk about it in depth as they have deliveries to get on with.

14:30

Steven Baxter heads to a funeral home to collect the body of another coronavirus victim.

He received a call the previous day from a man whose father had died. He couldn't afford what the company was charging for a cremation and needed someone else to take over.

As he collects the body, Steven is angry about what he sees as exploitation of victims of a health crisis. He believes the price that was being charged is four times the average in the city.

16:20

It's the news everyone had been dreading. The result for the fifth employee tested at Faith Willett's home comes back positive.

She tells herself there's no time to feel - she needs to act.

She begins the difficult process of alerting residents and their families.

AFP

AFP

17:00

While speaking to a patient earlier in the day who was unable to get a mask, doctor Michael Morgenstern shows him how to fashion one out of a T-shirt.

He decides others may also need to see how to do this so shoots a video and shares it online.

18:00

As Sarujen drops off his last package, he gets a call asking him to join a team meeting about the future of the company.

At the meeting, they agree that the delivery drivers will take the chefs to and from work so they can avoid trains.

He is happy that he can continue working but exhausted from stress over the virus and the day's concerns over his job.

20:00

Steven Baxter returns home from the funeral home but his day isn't over.

His twin sons are playing basketball in the backyard. They ask him if he has to shower. When he says yes, they know what sort of day he must have had.

For the next few hours, he deals with calls from more bereaved families. He doesn't have time to speak with his wife, who is also a funeral director.

He falls asleep before his children. He has to be at another nursing home to collect another body at 04:00.

20:22

Jennifer has a hot bath and is ready to crawl into bed. Even though her hours haven't changed, she feels much more exhausted than before.

As she responds to more texts about patient care, she reviews how she feels. Achy, tired, sore throat. She wonders if she should get tested.

20:40

Faith Willett gets a call from a nurse who says she can't do an upcoming shift. She isn't unwell but news has got around about today's positive result at the nursing home.

The nurse's skills and training are invaluable. Faith can't understand the woman's decision, which she sees as jumping ship at a time of crisis.

21:00

Jennifer watches an episode of TV sitcom Friends. It is all she can manage to watch these days - she struggles to focus on anything too heavy.

She has a goodnight FaceTime with her children before turning out the lights. She hasn't seen them in person for eight days.

As she closes her eyes, she makes a mental note: "Thank the cast of Friends when this is over."

22:00

Kathleen Flanagan has been home for about an hour. It was the usual routine - a shout of "hello" to the family again, clothes in the washing machine again, a shower again.

She has time for only one meal a day at the moment. Today it was eggs and spinach, again.

She goes to sleep with The Office playing on Netflix. It is her winding-down time before she has to start again. But her phone stays close in case anyone needs her.

23:58

There are only a few hours before Faith has to start work again. She has been trying to get some rest but is woken by an email reminder from the department of health about an upcoming call about the virus.

There has been no news from her nursing home of new or worsening symptoms. But that doesn't mean she can relax.

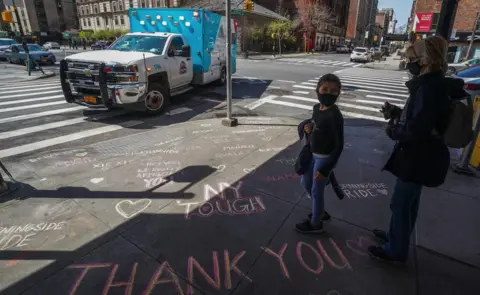

Throughout this day, Tuesday 7 April, another 779 people died of coronavirus in New York state - a new high.

This grim record is surpassed again the next day.

Reuters

ReutersAll images were taken on Tuesday, 7 April