Trump lifts restrictions on US landmine use

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUS President Donald Trump has lifted restrictions on the deployment of anti-personnel landmines by American forces.

The decision reverses a 2014 Obama administration ban on the use of such weapons, which applied everywhere in the world except for in the defence of South Korea.

The Trump administration said Mr Obama's policy could put US troops "at a severe disadvantage".

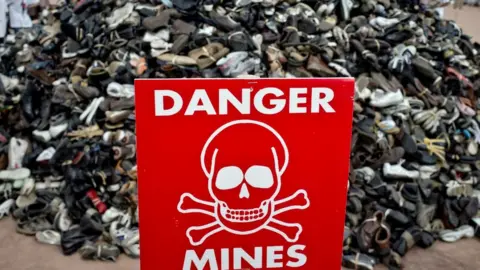

Thousands of people are injured and killed by landmines every year.

US forces will now be free to use the weapons across the world "in exceptional circumstances", the White House said.

The US is not a signatory to the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, which restricts the development or use of anti-personnel land mines.

What has changed?

The Obama-era ban applied to the US military everywhere but on the Korean Peninsula. That exception was made under pressure from military planners, to protect US troops based across the de-militarized zone from the North Korean military.

Mr Obama also ordered the destruction of landmine stockpiles not made to defend South Korea. But the Trump administration has now scrapped that policy, stating that the president was "rebuilding" the US military.

"The Department of Defense has determined that restrictions imposed on American forces by the Obama administration's policy could place them at a severe disadvantage during a conflict against our adversaries," a White House statement said, adding: "The president is unwilling to accept this risk to our troops."

Mr Trump has given the all-clear for the use of "non-persistent" landmines that can be switched off remotely rather than remaining buried beneath the ground.

Why is Trump doing this?

US Defence Secretary Mark Esper said landmines were vital to its military.

"Landmines are an important tool that our forces need to have available to them in order to ensure mission success and in order to reduce risk to forces," he told a press conference.

"That said, in everything we do we also want to make sure that these instruments, in this case landmines, also take into account both the safety of employment and the safety to civilians and others after a conflict."

Rachel Stohl, an arms control expert at the Stimson Center think tank in Washington, called the decision "inexplicable".

"I have no idea if it's posturing or a reality that the US is claiming back the right to use landmines," she told the BBC. "It's inexplicable given all we know about these deadly weapons and the amount of money the United States has spent demining around the world," she added.

Ms Stohl said the decision put lives at risk and was another example of the Trump administration "defining its own rules and ignoring global standards of behaviour".

A risk to civilians despite technical wizardry?

While the Obama administration refused to join the global ban on anti-personnel landmines, it broadly sympathised with the aims of the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty.

Senior military commanders believed the effect of these weapons - denying an area to enemy advance - could be replicated by other weapons less dangerous to civilians once a conflict was over.

Now landmines will be more widely available to US commanders, the argument being that their absence leaves them at a disadvantage in relation to likely adversaries - perhaps a reference to the fact that neither Russia or China have banned or placed any restrictions on such weapons.

The use of antipersonnel landmines by US forces will only be in exceptional circumstances, says the Pentagon, and only "non-persistent types" - ie. versions that disarm themselves after a period, will be used. But campaigners will see this as striking at the international norm outlawing these weapons, and will argue that for all the technical wizardry many mines may still fail, remaining live and risking injury to innocent civilians.

How destructive are landmines?

The use of anti-personnel landmines has been banned by 164 countries, and yet they're still being used in conflicts around the world. There are an estimated 110 million anti-personnel mines still in the ground with more being laid every year.

In 2017, more than 7,000 casualties were caused by mines and other explosive remnants of war, including nearly 2,800 deaths, according to the Landmine Monitor.

More than 120,000 people were killed or injured by landmines between 1999-2017, according to the same group. Nearly half the victims are children, with 84% being boys. Civilians make up 87% of casualties.

The true number is almost certainly higher due to cases going unreported.