Why women are fighting back against hair oppression

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRecent efforts to ban hair discrimination have amplified the struggle for women of colour and their natural hair, particularly in the workplace.

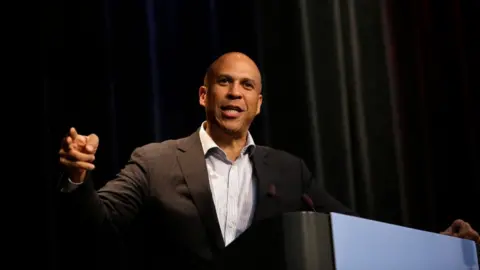

Senator Cory Booker has proposed the first bill in history to ban hair discrimination at the federal level.

The CROWN Act (Creating a Respectful and Open Workplace for Natural hair) was first introduced in California, making it the first state to pass a law that makes this form of discrimination illegal. This move was followed by the State of New York, and New Jersey became the latest state to pass this legislation.

"Implicit and explicit biases against natural hair are deeply ingrained in workplace norms and society at large. This is a violation of our civil rights, and it happens every day for black people across the country," said Senator Booker.

Joshua Lott/Getty Images

Joshua Lott/Getty ImagesWhile many incidents of discrimination in schools and the workplace have recently surfaced on the news and on social media, this deep-rooted issue has unfortunately been a common reality for many black men and women.

How are women of colour discriminated against?

A recent study by soap brand Dove found that a black woman is 80% more likely than a white woman to change her natural hair to meet social norms or expectations at work.

Tameka Amado, a young African American woman in Boston, says she has changed her hair "plenty of times" for work and school.

"When I was on the competitive cheerleading team, I was never allowed to wear my hair in its natural state. My coach made sure our hair was up and straight.

The repeated ironing of her hair caused it to start falling out in a her junior year, she says.

"For centuries our hair has been attacked. It's uncomfortable to know you have no control of how your hair grows, the only thing you can control is how you wear it and how you protect it, and to not have that freedom is discrimination. It only happens with us."

Laws like those proposed by Senator Booker give her hope, she says.

"It's long overdue. Policing our hair is just another systematic oppression," she says. "There is an entire industry that has become successful on the backs of hair discrimination. Chemical treatments like relaxers, hair extensions, wigs, were all created because this disgust for our hair texture."

Ms Amado's struggle between embracing her natural roots and being more susceptible to criticism and disfranchisement is a continuous battle.

"I want black women to enjoy their hair and whatever hair they choose to have but there will always be some kind of critique."

What are hairstylists saying?

Salon owner Wanda Henderson breaks down natural hair as "the state in which hair is not chemically treated to alter afro-texture hair" and includes many different styles.

"Natural hair is so wonderful to work with. The thicker it is, the stronger it is, and the longer it grows. It's stylish, more convenient and healthier."

Henderson promotes natural styles in her shop in Washington DC. She explains that taking the hair from its natural state is not healthy, and there can be long-term consequences.

"I've been doing hair over 40 years, and we did a lot of relaxers back in the 70s, 80s and 90s and with that came a lot of breakage, balding, and shedding when you apply chemicals to black hair and you don't keep it up."

Henderson says that many of her clients have experienced some sort of discrimination against their hair, but recent efforts and discussion have had a ripple effect.

"We get a lot of people now who want no chemicals, they just want all natural. We've gotten a large increase of that." She largely attributed this to more attention to incidents, legislation, and a push for black men and women to embrace their natural beauty.

The struggle between natural hair and acceptance transcends class and the corporate America realm. Current national anti-discrimination laws don't mention hair. This has caused many black men and women to attempt to push back against this form of discrimination on their own in schools, workplaces, and even Hollywood.

Gregg DeGuire/Getty Images

Gregg DeGuire/Getty ImagesActress Gabrielle Union made headlines recently because she says she was fired as a judge on NBC's hit reality show America's Got Talent because the hairstyles she wore were considered "too black" for the show.

NBC responded by saying saying they remained "committed to ensuring a respectful workplace for all employees" and take questions about workplace culture seriously.

Many other celebrities have also spoken out about their own experiences with their natural hair in the industry and the daily pressures they face.

How did we get here?

The policing of black hair dates back to slavery in the US.

Black women have always adapted in attempts to be accepted in society. When Africans were first enslaved and brought to the US, many of their heads were shaved to prevent the spread of lice but also erase their culture and identity as a form of assimilation. This stigma continued through the years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe invention of products like hair relaxers, chemical treatment and hot-combs were used to straighten Afro-texture hair, in order to mimic Eurocentric hair.

In fact, many jobs and public spaces didn't accept hairstyles mainly worn by black people. And in several cases that ended up in court, rulings were made in favour of employers. Dress codes would not mention race but would ban hairstyles mainly worn by black people in the workplace.

Until 2017, women in the military were restricted from wearing natural hairstyles including "twists, dreadlocks Afros and braids" because they were labelled "unkempt". Those who did not follow these guidelines were forced to cut their hair or wear wigs.

But this year, things have started to change. specifically, as individual states like California, New York and New Jersey have brought more attention to this issue.

Alongside this legal progress, the conversation on the subject has widened, amplified on social media.

"My black hair has defined me because systematic oppression has allowed that," says Ms Amado.

"My hair is empowering and through all the relaxers, flat irons, weaves, and braids, my hair tells a story. It's going to continue telling these stories through every kink and curl."