Why US lags behind on graphic cigarette warnings

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe US wants to put graphic images on cigarette packets - the first change to health warnings on tobacco products in 35 years. Other countries have long used such shock tactics to discourage smokers, so why does the US lag behind?

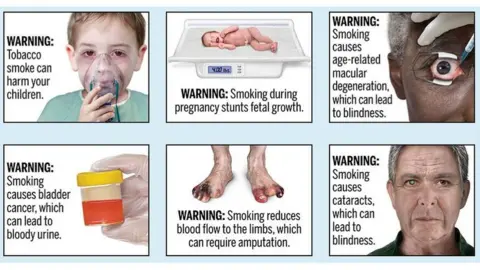

Grisly images of cancerous tumours and diseased lungs and feet.

Stark warnings that smoking can cause everything from blindness and bladder cancer to strokes and stunted foetal growth.

If the US Food and Drug Administration gets its way, these mandatory health warnings will feature on cigarette packets from 2021.

Those disturbing images - which are shown further down this article - would mark the first change to labels since 1984.

The FDA proposed a similar move nine years ago, but it was ultimately blocked in court by tobacco firms on the grounds of free speech.

The pictures may be an unwelcome addition for smokers in the US, but in many parts of the world such images are already part of the price of buying a packet of cigarettes.

FDA

FDAWhat is the FDA proposing?

If approved, new warnings from the FDA will feature "photo-realistic" colour images depicting the health risks of smoking.

"While most people assume the public knows all they need to understand about the harms of cigarette smoking, there's a surprising number of lesser-known risks that both youth and adult smokers and non-smokers may simply not be aware of," said Acting FDA Commissioner Ned Sharples in a statement.

The graphic warnings will cover the top half of the front and back panels of cigarette packages and at least 20% of the top area of cigarette advertisements.

FDA

FDA"The diseases embedded in these images will improve public understanding of the negative consequences of cigarette smoking," said Mitchell Zeller, head of the FDA's tobacco division.

Warnings first appeared on cigarette packages in the US in 1966, and were most recently updated in 1984. For the past 35 years, cigarette packages and advertisements have carried one of the same four warnings from the Surgeon General, noting health damage like lung cancer, heart disease and emphysema.

"Their unchanged content over decades, as well as their small size and lack of images, undermines the current warnings' effectiveness," the FDA said in a statement.

According to the FDA, 34.3 million US adults and nearly 1.4 million young people in the US, ages 12-17, currently smoke cigarettes. Despite declines in cigarette smoking, tobacco use is still the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the US, killing about 480,000 Americans every year - more than alcohol, HIV, car accidents, illegal drugs, murders and suicides combined.

Erika Sward, assistant vice-president of national advocacy for the American Lung Association, called the graphic warning labels "overdue".

"The bottom line is that graphic warning labels have been demonstrated in study after study around the world to deter kids from starting to use cigarettes and promoting adults to quit," she says. "It's so important."

How do other countries warn smokers?

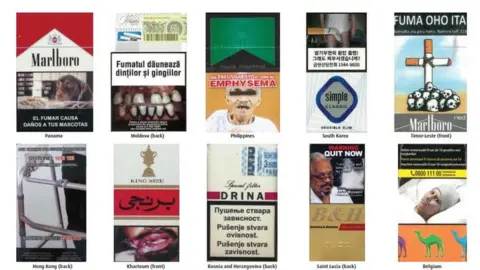

According to the World Health Organization, 91 countries already mandate strong graphic warnings on packaging, covering 52% of the world's population.

Canadian Cancer Society

Canadian Cancer SocietyIt's quite a jump from 20 years ago, when Canada became the first and only country to put graphic warnings on cigarettes. By 2007 this number had grown to nine - 5% of the global population - before gradually expanding to cover all 28 members of the European Union, and countries such as India and New Zealand.

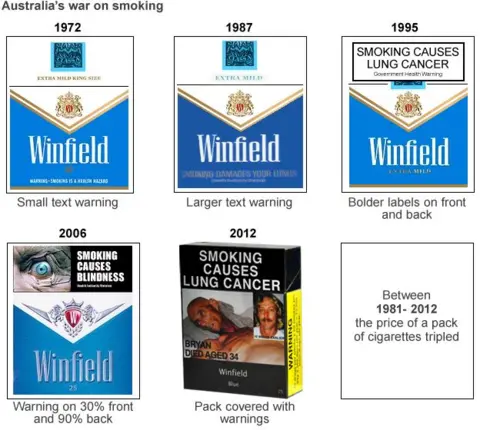

In 2012, Australia became the first country to use "plain packaging", which restricts the use of logos, colours, brand images and promotional information. It's considered the toughest type of restriction on cigarette packages.

Regulations there required that cigarettes be sold in plain brown containers, without any distinguishing features other than a brand and product name. Graphic health warnings depicting the consequences of smoking was ordered to cover 75% of the front of packs and 90% of the reverse. Even the colour - Pantone Cool Gray - and font - 2C Lucinda Sans Regular - was specifically mandated in the 2012 legislation.

Though WHO notes that the US has mandated "large warnings" covering at least 50% of cigarette packaging, they fail to meet the WHO's standards for best practices.

Why is the US lagging behind?

This new proposal is not the first time the FDA has tried to add graphic imaging to cigarette packaging.

In 2011, in response to demands from Congress, the FDA published a rule requiring graphics depicting the negative consequences of smoking on cigarette packaging. But the rule was thwarted when a federal appeals court found that the agency's plan undermined free speech protections.

Jonathan Havens, a former FDA lawyer who worked with the agency's then newly-established Center for Tobacco Products, says the First Amendment is the primary obstacle separating the US from other countries.

"Not every country has the First Amendment," he says, which extends protections to companies as well as individuals. "It's a pretty simple but agreed upon point."

Instead of warning consumers about specific health risks, the first round of FDA graphics were seen as a mere "shock and awe" tactic, and not a reasonable infringement upon tobacco companies' free speech.

"We take freedom of speech more seriously than most other things in our country," Mr Havens adds.

But experts disagree on whether the First Amendment should preclude graphic cigarette warnings.

"The Tobacco Control Act gives the FDA the authority they need to protect the public health," the ALA's Erika Sward says. "Time and time again, FDA and the [Obama and Trump] administrations have failed to act."

But it's still unclear if these new warnings will be met with with a challenge in court.

Using a "science-based approach" that focuses on health risks, the FDA is "trying to have a better and more defensive case" than the last time around, Mr Havens says. But, "that doesn't mean they're going to win."

Kaelan Hollon, a spokeswoman for Reynolds American, the tobacco company that led the 2011 suit, says they are "carefully reviewing the FDA's latest proposal for graphic warnings."

"We firmly support public awareness of the harms of smoking cigarettes," she says, "but the manner in which those messages are delivered to the public cannot run afoul of the First Amendment protections that apply to all speakers, including cigarette manufacturers."