A body donated to science - but used to test bombs

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA man who donated his mother's body to what he thought was Alzheimer's research learned later it was used to test explosives. So what does happen when your body is donated to medical science?

Last week new details of a lawsuit emerged against the Biological Resource Centre in Arizona, following an FBI raid in 2014 in which gruesome remains of hundreds of discarded body parts were discovered.

The centre, now closed, is accused of illegally selling body parts against the donors wishes.

Newly released court documents revealed that families of those whose bodies had been donated said they believed their relatives' remains would be used for medical and scientific research.

Jim Stauffer is one of the multiple plaintiffs suing the centre. He told Phoenix station ABC 15 he believed his mother's donated body would be used to study Alzheimer's, a disease she had, but he later found out it was used by the military to examine the effects of explosives.

He says on the paperwork he was given by the centre. he specifically ticked "no" when asked if he consented to the body being used to test explosives.

So how does the body donation business operate in the US, and what expectations do people have?

Why body donation is unregulated in the US

While organ donation is regulated by the US Department of Health and Human Services, body donation remains unregulated .

Buying and selling bodies is a felony but what is permissible is charging a "reasonable" amount to "process" a body. This includes removal, storage, transportation, or disposal.

What constitutes a "reasonable" amount is also open to interpretation. Facilities are largely able to set up their own internal practices and policies.

Nor is there any known national or global register to track how many bodies are donated for medical research each year.

But it's estimated thousands of people in the US donate bodies for education or research, believing their actions are charitable and the bodies will be used for medical science.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUniversity body donation centres will mostly use cadavers to teach medical students. Many institutions, such as the University of California, are committed to operating a transparent programme.

Others like the University of Tennessee's Anthropological Research Facility, known as "The Body Farm", operate more specific practices, like teaching forensic teams how bodies decompose.

Brandi Schmitt, executive director of anatomical services at the University of California, told the BBC that what happens to a donated body depends on the kind of centre it goes to.

"Anyone considering donation for education and research should ensure they know the purpose of the organisations to which they are donating, whether it is an academic institution, a state anatomy board, a private company, et cetera. and what they are giving their gift in support of."

Ms Schmitt says current regulations are not sufficient to protect donors and those working in medical science.

Getty Images

Getty Images"The Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA) was written by the Uniform Law Commission and is a state-level law that may be modified by the state [of California].

"It governs how to and who can make, amend and revoke an anatomical gift as well as the general type of gift use, such as transplant and clinical therapy and education and research.

"It does not address consent disclosures, specific uses, transfers, tracking, most aspects of final disposition or profit model."

Ms Schmitt says "additional regulation" is long overdue.

"The lack of more specific regulation and the variability has led to where we are currently with some tragic abuses of a donor or family's intent to make a positive impact through their gift.

"Existing regulatory codes should be enforced, and I believe it's beyond time for additional regulation including a clear authorisation and consent process so donors and families can make an informed choice," she says.

In addition to the UAGA, there are also other guidelines on how bodies should be handled after donation, such as those from the American Association of Anatomists.

It says: "Body Donation Programs should clearly describe the use of cadavers as it relates to institutional and educational needs."

The American Association of Tissue Banks is an accrediting organisation in the sector, although accreditation is not mandatory.

The Biological Research Centre in Arizona was not thought to be accredited and also operated as a for-profit business. It offered free transport services to pick up bodies and free cremation, making it appealing to low-income families.

Its owner Stephen Gore pleaded guilty in 2015 but was sentenced to probation. A number of families are now suing him and the company for mishandling bodies and not abiding by the promises made in their consent forms.

"People considering donation may be in a vulnerable state and it's wrong to exploit their grief or intent," Ms Schmitt says.

Body donation in other parts of the world

BSIP

BSIPIn England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the Human Tissue Authority (HTA) licenses and inspects organisations where bodies are donated for medical research.

There are about 19 institutions around the UK which accept body donations, with people usually choosing the nearest one to their home or to an area they are originally from.

People are referred to an institution through the HTA's website or by their GP, solicitor or local authority.

In other countries, religious beliefs may affect decisions to donate a body for medical research. For example, in some African countries even organ donation is a taboo, and desecration of the body is considered contrary to some religious teachings.

Aspetar

AspetarIn Qatar, a hospital where human body parts are imported for cutting-edge medical science research has been operating for 12 years.

The Aspetar hospital opened in 2007 and created the Visiting Surgeons Programme as a postgraduate experience for doctors from all over the world. Surgeons there do not use replica body parts but "specimens".

In a highly bureaucratic process that involves the joint work of six government ministries, real human body parts (mostly shoulders, knees, ankles and torsos) are imported, with most of the supply coming from the United States.

The immortal corpse

Although the gruesome details of what happened at the Biological Resource Centre in Arizona have drawn attention to the body donation industry, the practice itself is considered invaluable for understanding the human body.

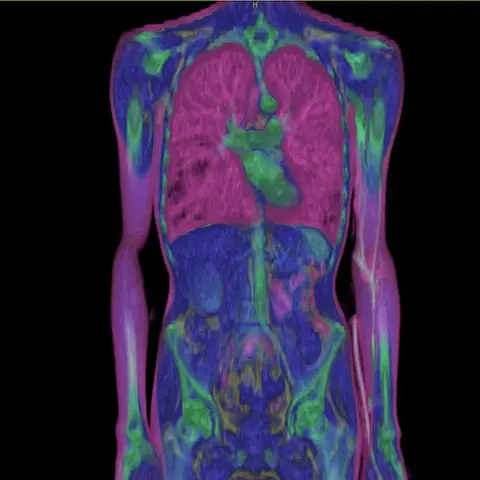

One of the most notable cases is that of Susan Potter. In 2015 the elderly woman from Denver donated her body to Dr Vic Spitzer from the University of Colorado for his Visible Human Project, a programme that transforms human cadavers into virtual specimens.

Susan's body was frozen and cut into 27,000 hair-thin slices. Each section was photographed and Potter is now known as an "immortal corpse", as the images are virtually stacked and rendered into a full 3D image of her body.