Supreme Court: Federal judges cannot block gerrymandering

The Washington Post via Getty Images

The Washington Post via Getty ImagesThe US Supreme Court declined to set limits on gerrymandering - the practice where voting districts are re-drawn in order to favour political parties.

The 5-4 vote on Thursday saw justices divided along ideological lines, with the court's conservative majority penning the opinion.

They ruled the federal government does not have the constitutional authority to regulate state election maps.

The decision could increase partisan redistricting after the 2020 census.

By tossing gerrymandering back to Congress and the states, the Supreme Court may have emboldened regional lawmakers to carry out partisan mapping after the next census is complete, in a move some say will result in noncompetitive elections.

The liberal justices condemned the majority ruling and said the practice of gerrymandering imperilled democracy.

Justice Elena Kagan asked in the dissent: "Is this how American democracy is supposed to work?"

What were the cases?

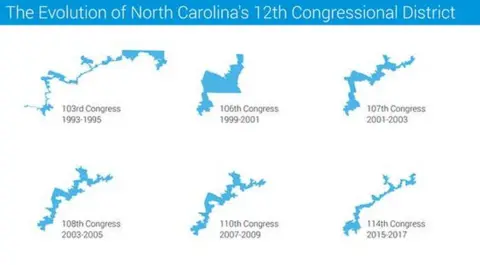

The Supreme Court examined two cases of partisan gerrymandering in North Carolina and Maryland, where voters and other plaintiffs sued the states for district maps they claimed were unconstitutional.

In North Carolina, the plaintiffs accused the state of discriminating against Democrats. In Maryland, plaintiffs claimed the maps discriminated against Republicans.

They argued the instances of gerrymandering violated the US Constitution, which says states must govern impartially and protects individual rights.

Plaintiffs in both cases won in lower courts, prompting the states to appeal to the Supreme Court.

In the North Carolina case, one of the Republican co-chairs of the redistricting committee had admitted: "I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country."

As the liberal justices pointed out in the dissent, these mapping efforts led to Republican candidates winning 10 of North Carolina's 13 seats while receiving 53% of the statewide vote in 2016, and nine out of 12 seats with 50% of the vote in 2018.

Dr Alasdair Rae

Dr Alasdair RaeSimilarly in Maryland, Governor Martin O'Malley said he decided "to create a map that was more favourable for Democrats over the next 10 years".

The mapping changes moved over 300,000 voters around districts to decrease the numbers of registered Republicans and increase the number of Democrats.

Maryland Democrats have won seven out of eight congressional seats despite never having more than 65% of the statewide vote.

What was the ruling?

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the majority opinion, saying that the top court could not rule on gerrymandering because there are no laws to direct it.

"We have no commission to allocate political power and influence in the absence of a constitutional directive or legal standards to guide us in the exercise of such authority."

Justice Roberts noted that the court "does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering".

"Nor does our conclusion condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void. The States, for example, are actively addressing the issue on a number of fronts."

He wrote that as there is no "fair districts amendment" in the constitution, only "provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply".

Partisanship gets a green light

The Supreme Court has been dancing around the issue of partisan gerrymandering - political parties drawing legislative district lines to secure the most seats - for decades. Justices at times appeared to be searching for a clean way to define when such efforts endanger the democratic process.

Now, with a newly reinforced conservative majority due to two Donald Trump appointments, the court slammed the door shut on this discussion - at least at a federal level. None of the proposed "tests" for determining what shouldn't be allowed worked, a bare majority of the justices held, and instituting any of them would open the courts up to an endless stream of lawsuits.

Because of advances in data science, gerrymandering has become a process conducted with near statistical certainty. Disfavoured voters are spread out between districts or packed into a handful of constituencies, weakening their overall power. It has become common to see a party win or lose seats far out of proportion with the total number of votes they receive statewide.

Now the court has given a green light for these practices to continue. While some challenges may continue by citing state constitutions, the legal debate on the national level is over for now.

What did the dissent say?

Justice Kagan wrote the dissent on behalf of the court's liberals - Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor.

She said gerrymandering "debased and dishonoured our democracy" by promoting "partisanship above respect for the popular will".

"For the first time ever, this Court refuses to remedy a constitutional violation because it thinks the task beyond judicial capabilities.

"The partisan gerrymanders in these cases deprived citizens of the most fundamental of their constitutional rights: the rights to participate equally in the political process, to join with others to advance political beliefs, and to choose their political representatives.

Justice Kagan argued it was not beyond the Supreme Court to regulate the practice, as it can make the system of democracy "meaningless", and the Court has a duty to "defend its foundations".

What's the reaction?

Some Republicans have spoken out in favour of the ruling, calling it a win for voters.

North Carolina Congressman Mark Walker said it was "a rebuke of the activist judges" - a view echoed by other Republican lawmakers in his state, who lauded their mapping efforts as fair.

Ohio Congressman Jim Jordan, the top Republican on the House of Representatives Oversight Committee, also praised the decision.

Allow X content?

Republicans currently control the majority of state legislatures, and thus have control over more districts than Democrats.

Others voiced their concerns over the pass given to such a partisan process.

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Voting Rights Project attorney Alora Thomas-Lundborg said: "The bottom line is voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around."

In Maryland, some Democrats who have benefitted from gerrymandering offered a more nuanced opinion.

Congressman David Trone, a Democrat in a district historically held by Republicans, told WMAR News there needed to be "a national standard to end partisan gerrymandering".