Are US veterans of Iraq, Afghanistan and Vietnam treated equally?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Iraq war was seen as a disaster - both by Americans and by people around the world. Yet those who fought in the war are nevertheless honoured, a striking departure from the way that service members were treated when they came home from Vietnam.

David Bellavia, a former US army staff sergeant, received the nation's highest combat award, the Medal of Honor, in June 2019. President Trump honoured him during a ceremony at the White House, describing his "bravery" and making him the first living recipient of the award for combat in Iraq.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe ceremony for Bellavia, who was surrounded by members of US congress, senior military leaders and others, reflects the honourable way that veterans of the Iraq war are treated in the US.

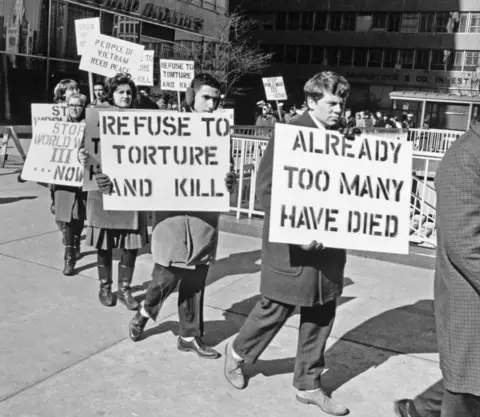

The treatment of Bellavia and other Iraq veterans stands in marked contrast to the way that those who fought in Vietnam were once regarded.

The wars in Vietnam and Iraq were both deeply unpopular in the US and abroad and were seen as dark chapters in history.

Approximately 58,000 US service members died or went missing in Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s and, according to some estimates, 200,000 South Vietnamese soldiers perished.

The toll of the war on civilians was staggering. As many as two million men, women and children died.

The Iraq war began in 2003, and over the years nearly 5,000 US service members died. More than half a million Iraqis were killed, according to estimates, in the conflict.

For many, the war in Iraq was a "fiasco", as one journalist, Thomas Ricks, entitled his book about the conflict.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYet the US troops who fought in the war have not been blamed for its failure or imbued with a sense of shame. Instead they are made to feel appreciated for their service in the military.

"Even if someone disagrees with the politics of the war, they still honour the veterans," says Jason Nulton, an administrator at Ohio Valley University in Vienna, West Virginia, and a US air force veteran who has written about the treatment of those who served in the military.

That was not the case after Vietnam. Veterans of that war recall being treated badly upon their return and bearing the brunt of the blame for a misguided war.

Back then veterans were seen not as "victims of a cruel war", historian James Wright argues in the New Yorker magazine. Instead, Wright explained, they were seen as "perpetrators of a cruel war".

One of the Vietnam veterans, Ed Barick, 73, a retired truck driver who lives in San Diego, served as a US army engineer from 1964-67 and returned to a nation that was deeply opposed to the war.

"I remember being spat on and called 'baby killer'", he says, adding in an understated manner: "It was a little bit irritating."

In contrast, US civilians are now more supportive of the Iraq veterans. Washington State University's Alair MacLean studied the way that US service members came back from battle, showing that World War II veterans fared better upon their return than those who served in Vietnam.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen the troops came home from Iraq, she discovered, they were seen as "different" from those who had not served in the military but were not stigmatised. Instead the Iraq veterans benefited from "symbolic capital", she wrote, setting them apart in a positive way from the civilians around them.

The shift in the public image of US veterans has occurred in part because of the way that the men and women themselves appear in public and also because of changes in cultural understanding of war and its aftermath.

During the Vietnam war, the troops who were badly injured on the battlefield had little chance of survival. But with new medical techniques and equipment, the US troops who were wounded in Iraq had a better chance of surviving - even when their injuries were serious.

Of the troops who were severely wounded in Vietnam, about 76% survived, according to Military Medicine. In Iraq, the survival rate climbed to 80% because of improvements in medical care on the battlefield and afterwards in medical clinics.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSeverely injured US service members were able to come home from Iraq, and as a result the effects of the war were more visible. Civilians in the US saw wounded veterans, men and women who lost limbs, carrying on with their lives. This helped to bring the war home for the civilians, showing them the impact of war in a visceral way.

In addition, people in the US, whether they live in civilian or military worlds, are now more likely to talk about the psychological impact of war than they were in the past. As veterans of both the Vietnam and the Iraq war explain, the stigma attached to post-traumatic stress still exists, but it is less pronounced than before.

David Hamilton, who became a stand-up comedian after serving as a US army specialist in Baghdad from 2005-06, says he received loads of support from his community immediately after returning to California.

As he landed at the airport he saw a "bright yellow and white" poster that had the name of his unit on it. He says the poster looked "like love, energy and time had been put into it".

A warm homecoming, he says, especially compared to the way that people were treated when they came back from Vietnam.

The personal toll that the Iraq war has taken on individuals, whether through physical or psychological challenges, has changed the overall narrative of the war and had an impact on the reception that veterans receive in society. In the end, civilians are more accepting of the men and women who served in Iraq than they were of those who fought in Vietnam.

Most people in the US still believe that the Iraq war was a mistake. Yet even its critics see the bestowing of the medal on Bellavia, "a model of leadership and personal sacrifice", says Pete Mansoor, an Ohio State University professor who served in Iraq, as a positive gesture.

After the war, Bellavia went back to civilian life. He he wrote a memoir - House to House - about the battle in Fallujah, and is now the host of a radio station, in Buffalo, New York.

Looking back at his experiences in Iraq, he said that he was not concerned about the politics of the war and that it was not his place to evaluate its merits.

"We have nothing to apologise for," he told reporters as he prepared to receive his medal.

"We serve our country. We do what our leaders tell us to do."