Bernie Sanders: What’s different this time around?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2016 Bernie Sanders arrived on the Democratic presidential scene with all the surprise of a thunderclap in a blue sky.

He set fundraising records, drew rally crowds of tens of thousands and, for a time, cast the once-seemingly inevitable nomination of Hillary Clinton in doubt.

Now he's back for another run at the top prize, with new advantages - and obstacles.

This time around he's fighting a two-front campaign, against establishment front-runner Joe Biden and fellow progressive champion Elizabeth Warren.

And then there are nearly two dozen other presidential hopefuls, nipping at his heels from every direction.

It's a political high-wire act that will require discipline and a deft touch to manage.

Is Sanders up to the challenge?

Feeling the Bern 2.0

Earlier this month the Sanders campaign swung through California, which was the last major battleground in his 2016 primary season. Squint a bit, and it seems like nothing has changed from those heady days. At a rally in San Jose, half a dozen souvenir vendors vied for the attention of the throng of Bernie faithful. His A-list of warm-up speakers from 2016 was reassembled - Harvard Professor Cornel West, actor Danny Glover and Vermont-based ice-cream mogul Ben Cohen of Ben & Jerry's fame.

When Sanders took the stage, he railed for 35 minutes against the oligarchy, multinational corporate executives, Wall Street bankers and the 1% of Americans who own more than 40% of the wealth in the country. He repeated calls for universal government-run healthcare, free college tuition, environmental regulation and a nationwide $15 minimum wage.

It was chapter and verse from the 2016 hymnal.

"The atmosphere of his campaign is great, he has great ideas and great policies and lots of political experience," says Erin Armstrong, a 16-year-old high school student who attended the rally. "There are a lot of politicians who promise things, and they're not ever going to get done. But his kind of politics has made actual progress."

There is even a similar adversary this time around. In 2016, the Sanders movement viewed former Secretary of State Clinton as the face of a Democratic establishment that was out-of-touch with the progressive heart of the party. Now it's former Vice-President Joe Biden, whose political legacy is longer and perhaps - due to his outspoken support of laws like a draconian 1994 anti-crime bill - even more distasteful to Sanders supporters.

"I meet so many people who say they're for Bernie or Biden," says Kristoffer Hellen, a supporter from Santa Cruz who sports a Bernie tattoo on his arm. "It's like, 'I'm for Mussolini or Gandhi'."

Although Sanders didn't mention Biden at his San Jose rally, he took aim in a speech to a convention of California Democrats in San Francisco the following morning, riffing on a line from a Biden campaign aide that described his boss's environmental policies as an attempt to find a "middle ground".

Sanders was having none of that.

There is no middle ground "when the future of the planet is at stake", he thundered. No middle ground on healthcare, abortion, gun control, immigration or income inequality.

As he did in 2016, Sanders is painting in bold colours and brooking no compromise - and the crowd of progressives and grass-roots activists ate it up. Although Sanders lost three years ago, the Vermont senator in his San Francisco speech drew a clear line from 2016 to today's campaign to a presidential victory in 2020 that would herald the arrival of a new era of progressive government.

"Together we began a political revolution whose ideas and energy have not only transformed the Democratic Party, but have transformed politics in America," he said. "And today we take that revolution forward."

New twists

Political campaigns are like blockbuster films - massive undertakings with many moving parts, whose successes are difficult to replicate. It's never easy for a sequel to live up to the original. While the cast of characters may be the same, things that were once fresh may, after time, seem recycled and tired.

In San Jose, his crowd wasn't quite as big or as loud as his 2016 gatherings. One T-shirt merchant lamented that campaign swag wasn't moving like it did back then.

And while the backbone of Sanders' rhetoric is the same, there are some new twists and flourishes. There's a heavier emphasis on criminal justice reform and swipes at the "prison-industrial complex." More talk of his own personal story, including his childhood of living "paycheque to paycheque". His wife, Jane Sanders, has joined the list of campaign surrogates, offering a more personal look at the candidate.

It's all part of the Sanders campaign's attempt to expand on the successes and avoid the mistakes of 2016.

There are a number of ways this iteration of the Bernie political crusade is clearly better positioned for victory. In 2016, it was frequently a slapdash, shoestring operation ill-prepared for the scope of the national contest.

"When we began the campaign back in May of 2015, there was no way to know how quickly the campaign was going to grow and how much grass-roots support there would be," says Jeff Weaver, who ran the Sanders campaign in 2016 and is now a senior adviser to Sanders. "So the campaign really could not keep up."

This time around, he says, Sanders has a much more sophisticated nationwide electoral infrastructure. The Vermont senator's Our Revolution organisation - picking up where his 2016 effort left off and developed over three years - effectively served as a turnkey national campaign, just waiting for the green light.

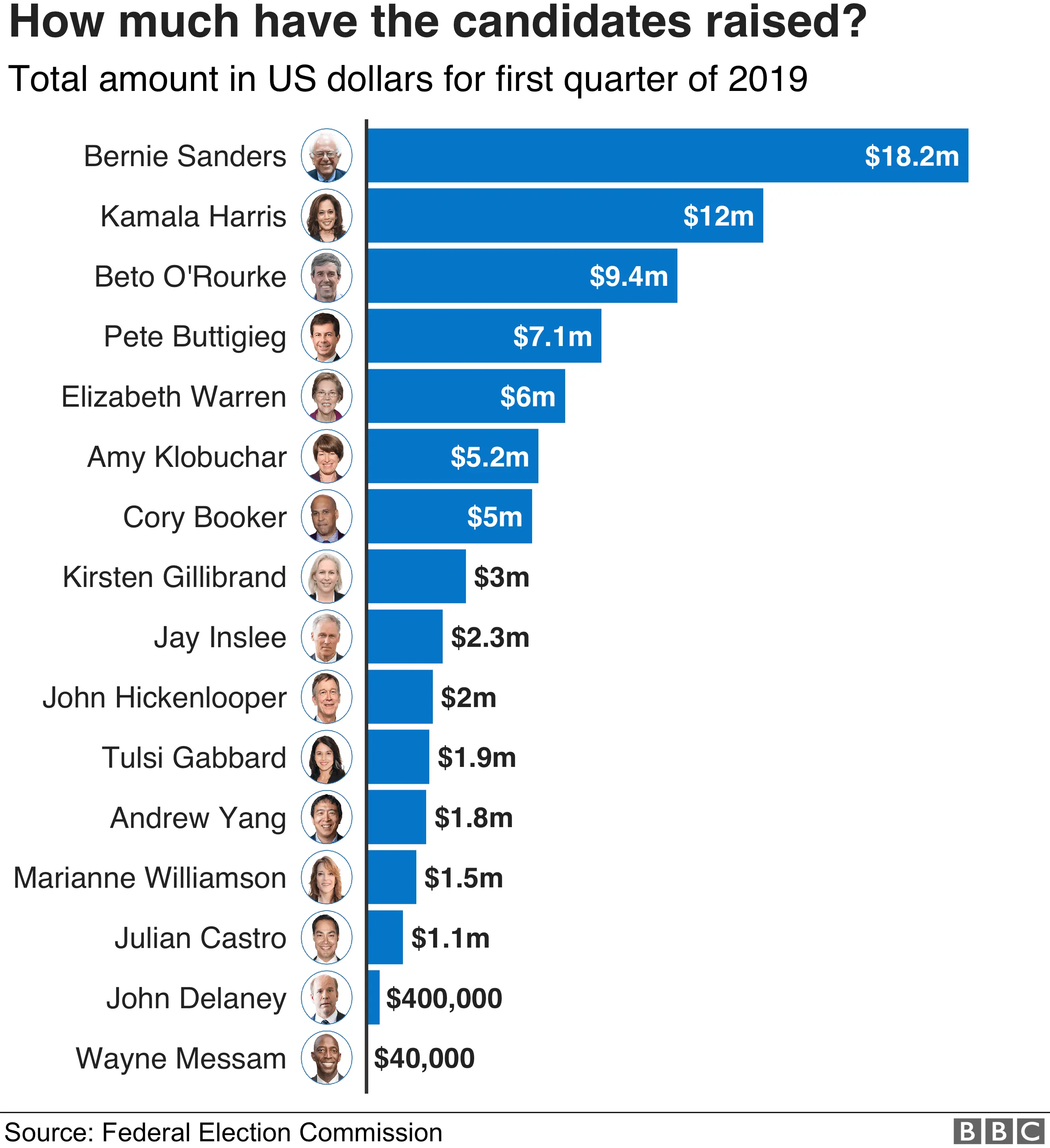

Sanders boasts a volunteer list of over a million people, and can turn on the money faucet from his grass-roots donor network with seeming ease. In the first quarter of 2019 fundraising, he pulled in $18.2m - easily outpacing the rest of the Democratic field (which excluded Biden at that stage).

In 2016 Sanders lost to Clinton by a razor-thin margin in the Iowa caucuses, demolished the former secretary of state in New Hampshire, posted another narrow defeat in Nevada and then ran into a brick wall in South Carolina and the following Southern primaries, due in large part to his inability to win over black voters.

This time, Sanders has spent considerable time and effort trying to expand this support. His campaign team is more diverse, he has courted black leaders across the South and - as demonstrated in his San Jose speech - he is spending more time talking about social justice issues.

"Sanders made tremendous strides in introducing himself and winning the support of African-Americans last time," Weaver says, noting that as the 2016 primary season progressed, Sanders won a growing percentage of the black vote.

Kenzie Smith, a community activist from Oakland who heard Sanders and other Democrats speak in San Francisco, is not so sure.

"There are a lot of racial equity issues he hasn't addressed that I wish he would," he says.

An eye on past mistakes

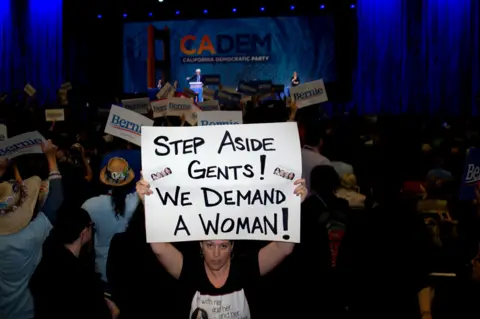

Sanders also has attempted to anticipate and address some of the criticisms that dogged his 2016 campaign. There were concerns that his movement created an atmosphere, both within the campaign and among the legions of supporters, that could be insensitive to women - the so-called "Bernie bro" phenomenon. Even prior to his formal campaign launch, Sanders made clear that he would not tolerate such behaviour - and some of his supporters suggest the problem was overhyped.

Getty Images

Getty Images"A lot of the Bernie Bro narrative was coming from the fact that Hillary Clinton was his opponent, and she's a woman," says RoseAnne DeMoro, the former head of the National Nurses United, a union that strongly backed Sanders in 2016. "It didn't really matter that we had a phenomenal base of really incredible women, it was just a campaign tactic on the part of Clinton."

Sanders' past as an antiwar activist has also come under recent scrutiny, including in a high-profile New York Times article and interview. The senator bristled at questions about his patriotism, and at a San Francisco event hosted by the liberal advocacy group MoveOn, he offered a full-throated defence of his past activities.

"Recently I have been attacked because of my opposition to unnecessary wars," he said. "I make no apologies as a young man for opposing the war in Vietnam. I make no apologies as a congressman for doing everything that I could to prevent the disastrous war in Iraq."

There have also been concerns that Sanders' self-identification as a "democratic socialist" could limit his appeal to a wider America electorate. Last week, in Washington, DC, he gave a speech attempting to define his views as in the tradition of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's 1930s-era "New Deal", which created the social safety net and workplace protections.

"I do understand that I and other progressives will face massive attacks from those who attempt to use the word 'socialism' as a slur," he said. "But I should also tell you that I have faced and overcome these attacks for decades - and I am not the only one."

Then there's the fact that, at age 79 on inauguration day, Sanders would be the oldest person to serve a first presidential term by nine years. The way his campaign appears to be confronting this reality is by demonstrating the senator's stamina on the campaign trail.

"The guy has got endurance beyond all of us," DeMoro says. "I have been on the campaign trail with Bernie, and it is exhausting. He can go the distance."

The electability challenge

The overriding attribute Democrats seek in their party's presidential candidate in 2020 is that they are able to defeat Donald Trump.

While issues like healthcare, climate change, immigration and education are important, they all take a back seat to unseating the current White House occupant.

It's a dynamic every Democratic campaign has had to grapple with, but it presents a particular challenge to the Sanders, whose 2016 effort was an explicit pitch to elevate principle and policy over what Clinton advocates touted as her strong "political viability".

This time around, Sanders and his supporters are trying to make the case that the 2020 election will be won because of his principle and policy, not in spite of it.

At the rally in San Jose, ice-cream mogul Cohen repeatedly shouted "Sanders beats Trump," spinning and waving his arms in a near frenzy of enthusiasm. It was a cry echoed the next day by Bernie supporters in the lobby outside the San Francisco convention hall.

In his address to the convention, Sanders made his case.

"In my view, we will not defeat Donald Trump unless we bring excitement and energy into the campaign," he said, "and unless we give millions of working people and young people a reason to vote and a reason to believe that politics is relevant to their lives".

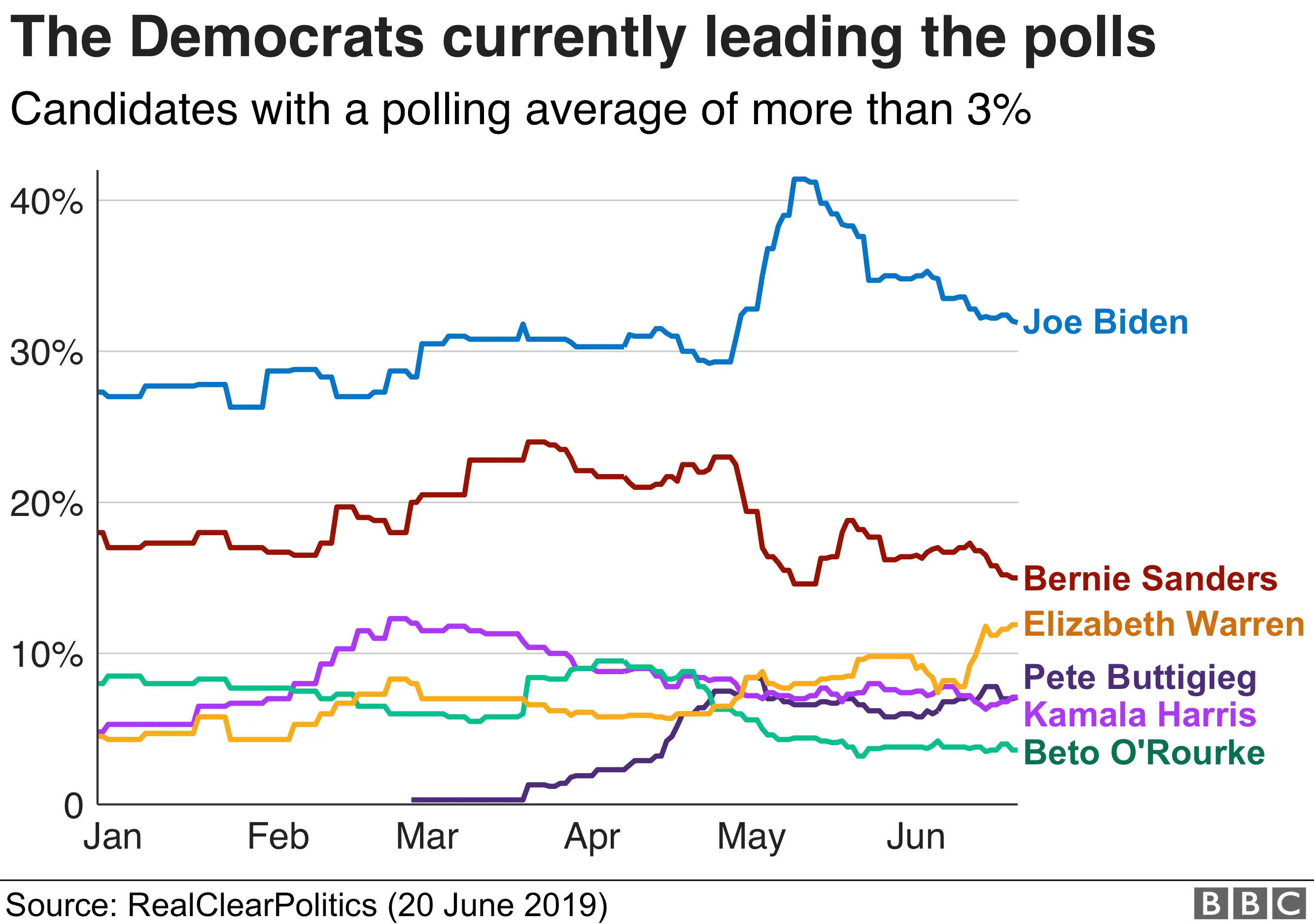

Sanders is aiming his electability argument, along with his "middle ground" denunciations, directly at Biden, who - at least according to early polls - has benefited from the support of those who see him as most able to win back the Midwestern states that Clinton lost to Trump in 2016.

The Sanders camp vigorously disputes this and says its own internal polls show the Vermont senator beating Trump in key Midwestern states. The weekend Sanders was in San Francisco, one particularly adventurous individual went so far as to spray paint "Biden can't win Michigan" on a highway sign outside of the city.

"It's literally the identical dynamics as last time," says DeMoro. "The Democratic Party establishment has somewhat overtly anointed Joe Biden as the candidate and Bernie as the outsider who can't beat Trump, when in fact Trump won because he was an outsider."

It's a lie, she adds.

The Warren 'threat'

For the Sanders camp, all of the aforementioned obstacles have largely been predictable. And Joe Biden's entry to the race presented a familiar challenge requiring familiar, well-practised tactics. Insider versus outsider. Corporate friend versus grass-roots champion. Status quo versus revolutionary change.

The new twist in 2020 is the woman coming at him from his left flank in that crowded field.

Elizabeth Warren, the two-term senator from Massachusetts and former Harvard professor, is as much a darling of the progressive left as Sanders. While her brand of politics leans more heavily toward tempering the excesses of free-market capitalism rather than his proposed big-government programmes, she's been steadily gaining in early voting state and national preference polls, while Sanders has stagnated or sagged.

In a few recent surveys, she has placed ahead of the Vermont senator for the first time since he entered the race.

Her campaign, which stumbled out of the gate trying to respond to her unfounded claims of native American heritage, has found its footing with her detailed "I've got a plan for that" policy menu, many of which - like student loan forgiveness and wealth tax - build on themes that were at the heart of Sanders's 2016 appeal.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Elizabeth Warren is fantastic, but her approach is still different than Sanders," says Alan Minsky executive director of Progressive Democrats of America, which recently voted to endorse Sanders over Warren.

"Changing the situation we have, with all the endemic social crises, is going to take consistent political engagement," he adds. "Bernie Sanders promises that. And I think a technocratic president with very strong progressive policies is going to learn very quickly that they need that kind of support."

That's a very nuanced pitch to make in the heat of the campaign, however, and the threat she poses to the Sanders campaign may require a sharper response. At least at this point, it's not clear they know how to pull that off without angering some of their own supporters who admire Warren.

"I think what the campaign has and will focus on is the fact that Bernie Sanders has been a consistent standard-bearer for his issues for decades," campaign adviser Jeff Weaver says. "He was the one in 2015 who took up the progressive mantle in the nominating process. He got 43% of the vote in the Democratic primaries last time. At this particular moment, he is the best candidate to carry that vote not only in the primaries but also in the general election."

Who is Sanders up against?

A few weeks ago, an anonymous Sanders adviser said that Warren "fundamentally fails" the electability test. Sanders campaign manager Faiz Shakir quickly walked that back, however, reportedly telling the Warren team that the view "doesn't reflect Bernie's thoughts".

Earlier this week, after Politico ran an article saying moderate Democrats appeared to prefer Warren to Sanders, Sanders himself retweeted it, adding that the "corporate wing of the Democratic Party is publicly 'anybody but Bernie".

It was guilt by association for Warren (despite her refusal to take corporate donations or hold big-money fund-raisers), but even an indirect attack hasn't gone over well with some Sanders allies. Waleed Shahid, communications director for the Justice Democrats, called the tweet "pretty disappointing and unnecessary". Charlotte Clymer, another progressive activist, said it was "childishness".

Sanders would later tell an interviewer that the tweet was not directed Warren, but the episode illustrates just how dangerous any move against the Massachusetts senator might be. Not only would it divide progressive ranks, it also threatens to remind voters of the divisions created by his 2016 campaign against Clinton - another female candidate - and some of the hard feelings that endure to this day.

A path forward

Perhaps in a turn of good fortune for Sanders, he will not share the stage with Warren in the first round of Democratic presidential debates in Miami next week. Instead, he gets to square off against Biden, creating a much more favourable contrast.

Given the level of attention the debates are sure to generate, a successful showing there will go a long way toward helping the Sanders campaign escape its current doldrums.

"Bernie Sanders is like a candidate from heaven," Minsky says. "He speaks in 12-word soundbites, and he gets the point across. He'll be very powerful in the debates because people will understand what he stands for."

Even if the debate doesn't deliver a bump or a surge or a change of narrative, there's still seven months until the primary voting begins - plenty of times for fortunes to change and then change again.

Bernie Sanders has two things that any politician hoping to win the presidency loves the most - a dedicated core of loyal supporters and campaign coffers full of cash. Those two strengths give him the ability to ride out the bumps along the way and go deep into the primary season, if not to the very end.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe senator likes to boast that his movement has redefined the mainstream of the Democratic Party, taking issues that used to seem "crazy" and making them core principles. A listen to the rhetoric from most of the two dozen candidates on campaign trail tends to bear this out.

Win or lose, the Sanders campaign has made a lasting mark on America politics. But movement to the left is not transformation; adoption of ideas is not revolution.

"We've got to stick together, we've got to struggle together, we've got to stay together," Harvard Professor Cornel West shouted to the crowd in San Jose. "We are going to win this one. We are going to win this time!"

The crowd roared like they believed him. Or, at least, they roared because they wanted to believe him.

He may be right. But if Bernie's revolution is going to be ultimately successful, it still has a long way to go.

Follow @awzurcher on Twitter