Trumplomacy: Five takeaways from Pompeo trip to Middle East

ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS via Getty Images

ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS via Getty ImagesThe US secretary of state's seven-day tour of the Middle East was an effort to reassure Washington's allies about the US withdrawal from Syria and draw the region together against Iran.

On the heels of abrupt changes in President Donald Trump's Middle East game plan, Mike Pompeo visited Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Oman.

After accompanying the secretary of state on part of this rapid round of diplomacy, here are my key takeaways.

1. Mohammed Bin Salman is here to stay

Riyadh is different than when I last visited three years ago.

The power of the religious police has been curbed - some women have even traded black abayas for more colourful cloaks, and taken off their headscarves.

True, that's only in very small numbers, but the change is striking.

Women are now allowed to drive; they're being actively recruited into the workforce; and they sit next to men at the cinema and at rock concerts - forms of public entertainment that until recently were banned, yet are now being promoted by the government.

Women to whom I spoke gave credit to the Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman.

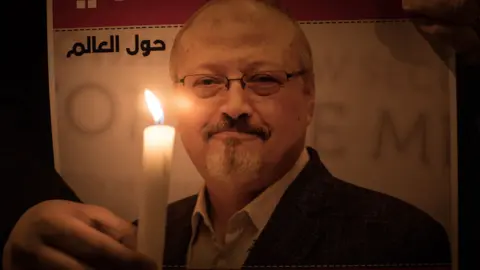

One told me she'd been worried that he'd lose power because of the international backlash over the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe crown prince, or MBS as he is known, has been accused of ordering the killing carried out by a hit team in a Saudi consulate in Turkey last October.

The woman was afraid that anyone who might replace MBS would roll back the reforms. But 100 days since the killing it's clear that won't happen.

After the limited cabinet reshuffle ordered by King Salman earlier this month, MBS holds the same power and his allies still serve in government.

However, the king also revived structures for making national security decisions that had been sidelined, suggesting he was trying to address issues that led to the crisis in the first place.

2. But the crisis isn't over

The key to how this crisis plays out lies in the strength of the international backlash, especially that of the United States.

President Trump has stood by Mohammed bin Salman despite a CIA assessment that he probably ordered the killing.

Secretary of State Pompeo has supported the president's viewpoint. But he's also pressing for accountability, and before his trip a senior State Department official told us that the Saudis had not reached an acceptable "threshold" in that regard.

Something that might help get them there is the fate of the crown prince's former media adviser, Saud al-Qahtani. The US has sanctioned him, determining that he was "part of the planning and execution operation" that led to Mr Khashoggi's death.

The Saudis have demoted him but, it seems, little else, according to the Washington Post and it does not appear that he is one of 11 suspects in a Saudi trial that got under way earlier this month.

Mr Pompeo, however, had nothing new to report. "No change," he told us after meetings with the king and the crown prince.

They had repeated their assurances that they would hold everyone responsible for the crime to account, but were still in the "fact-finding" process, he said.

FAYEZ NURELDINE

FAYEZ NURELDINEThe secretary of state didn't strike any urgent or critical notes. His aim is to manage this strategic relationship through a turbulent time.

The US senate, on the other hand, has been very critical, and much depends on how vigorously congress continues to scrutinise the matter.

The other bellwether is international investment: the crown prince needs it for his ambitious economic reforms.

Top business executives boycotted his recent investment conference, but the Financial Times correspondent in Riyadh, Ahmed al-Omran, told me that so far they did not seem to be cutting business links.

Still, Mr Omran said recovery would take a while because the reputational damage had been big. "One government official described it to me as 10 times worse than 9/11 [which was carried out largely by Saudi hijackers]," he said.

More from Barbara

3. It's all about Iran (and Israel)

Secretary Pompeo made clear that the Trump administration's top Middle East priority is to counter Iran, to stop its "wave of regional destruction and global campaign of terror".

That was a crucial theme of his speech in Cairo setting out US policy, suggesting that this would be the benchmark for judging America's still largely authoritarian Arab allies.

He also hailed signs of "steps toward rapprochement" between Israel and Arab states. This was necessary for "greater security in the face of shared threats," he said, promoting a Sunni Arab and Israel axis against Iran.

Mr Pompeo's message about Iran, if not Israel, was by and large well received among Sunni Arab leaders. Most also consider Shia Persian Iran to be a foe, although some more than others.

It was difficult to say, though, whether Mr Pompeo made progress.

He didn't give much detail about how he wanted Arabs to roll back Iran's influence, beyond enforcing sanctions.

STR

STRConfronting Iran militarily would mean taking on the militias it backs in various countries.

That's complex asymmetrical warfare in which few Arab states are willing to engage and it's been a disaster when they have, as in Yemen.

Mr Pompeo talked about expanding what he calls the coalition against Iran with an international conference next month in Poland. But he also acknowledged that an ongoing regional feud between Qatar and its Arab Gulf neighbours was weakening the anti-Iran front.

In a rare moment of pessimism, he admitted to US embassy staff in Qatar that the rift appeared no closer to resolution and "I regret that."

4. Mixed messages on Syria

Before Mr Pompeo's trip, President Trump abruptly declared that the Islamic State group (IS) had been defeated and announced a rapid withdrawal of US troops from Syria.

This vastly complicated things for the secretary of state.

By the time he departed for the Middle East, Mr Trump's national security officials had persuaded the president to slow down the withdrawal because IS wasn't actually quite defeated.

But they were still scrambling to formulate a plan as Mr Pompeo tried to reassure Arab allies that the US was not retreating on its commitment to their security interests, and it showed.

His rhetoric remained bold and unapologetic - the US exit was a tactical change, not a retreat, given there were other military assets in the region it could employ, he said; the US would "expel every last Iranian boot from Syria", he promised, even though it was withdrawing the troops that would have given it leverage to do that.

But the reality was confusion. On a separate trip, National Security Advisor John Bolton laid down conditions for the withdrawal, including the protection of America's Kurdish allies.

This triggered a furious response from Turkey, disrupting the State Department's delicate negotiations to secure a safe zone between Turkey and the Kurdish regions of Northern Syria.

Mr Pompeo had barely caught his breath when President Trump threw another spanner into the works, posting a tweet threatening Turkey with 'economic devastation.'

The secretary of state passed when we asked him what the president was talking about. "You'd have to ask him," he replied, a rare example of him not reflexively defending the president.

The day after Mr Pompeo returned from the Middle East, IS militants killed four Americans in northern Syria, just as Vice-President Mike Pence made a speech again declaring the group had been defeated.

With such a muddle in Washington, Middle East allies could be forgiven for being confused about US policy despite Mr Pompeo's reassurance tour, and few doubt that in Syria, at least, the administration is in retreat.

5. A religious experience

Mr Pompeo began his overture to the Middle East with a statement of faith.

In his Cairo speech, he declared that he was an evangelical Christian who kept a Bible open in his office to remind himself of "God, his Word, and the Truth".

A visit to a grand new cathedral built by the Egyptian president was one of the highlights of his trip. He seemed truly excited to be there and spoke with real admiration about what he saw.

"The Lord is at work here in Egypt," he told journalists: the cathedral was a "stunning testament to the Lord's hand… a truly remarkable place where you can see religious freedom at work."

He praised President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi and called Egypt a "land of religious freedom and opportunity".

Religion is the language of the Middle East and it could be an advantage for Mr Pompeo to speak it, especially as he maintained a tone of prayerful respect when he visited the grand new mosque that was also part of President Sisi's project.

MOHAMED HOSSAM

MOHAMED HOSSAMBut his enthusiasm about religious freedom in Egypt was notable for his failure to acknowledge the political repression in the country.

He didn't mention the 60,000 political prisoners the regime is thought to be holding. In his speech he didn't mention human rights at all.

And his brand of evangelical faith can colour the administration's approach to the Middle East in ways that are divisive: his language on Iran framed US policy as one of good versus evil, describing the Islamic Republic as a "cancerous influence".

The Trump administration's strong support for Israel is also a key tenet of evangelical beliefs.

While Mr Pompeo raised Israel's interests several times in his speech, he did not balance that with any mention of Palestinian rights and concerns.